The last action in the illustrious life of Adilson “Maguila” Rodrigues, who died on the 24th, at the age of 66, was to donate his own brain for research into chronic traumatic encephalopathy. But how easy is it to make this type of donation? Well, if you’re thinking about something similar, no matter how interesting the possibility is, don’t expect it to be something simple.

The former boxer’s brain is now in the USP Biobank for Brain Aging Studies, or, in a shorter version, USP’s brain biobank.

The biobank has existed since 2004 and has around 4,000 brains stored.

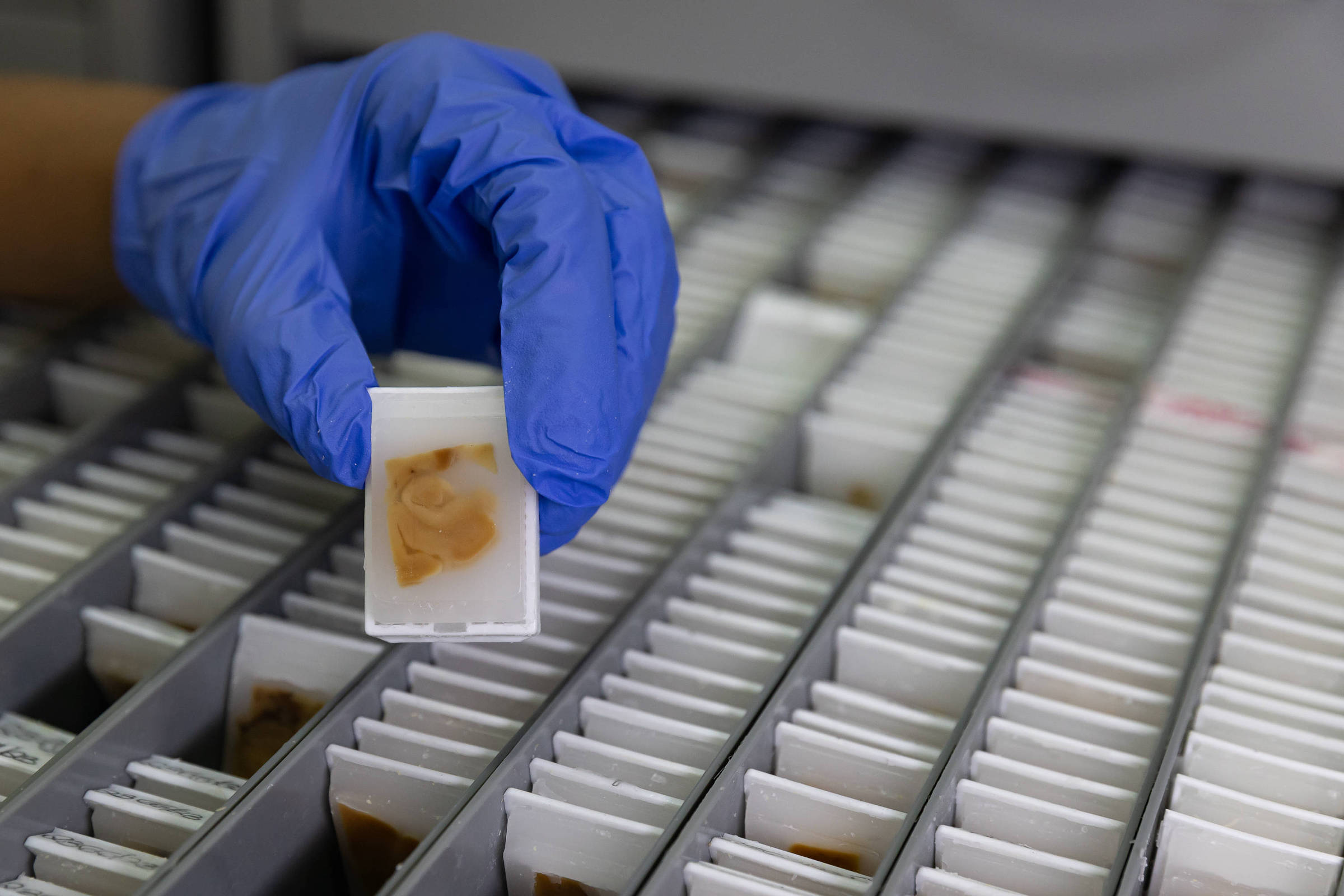

Are you imagining shelves loaded with jars containing brains floating in liquid? This image could not be further from reality.

The archive, in fact, is made up of large drawers in which several small slices of brains are stored. It is these little pieces that serve as objects for current and future research.

The biobank’s brains arrive there through the Death Verification Service (SVO), which is located in the USP Faculty of Medicine building, in Pinheiros, in the west zone of São Paulo. “People confuse it with the IML [Instituto Médico-Legal]”, says Renata Leite, coordinator of the USP biobank.

She explains that cases of death due to natural causes go to the SVO, while the IML, in general, deals with violent deaths.

According to the coordinator, 14 thousand deaths arrive at the service per year. It is within this universe that biobank researchers work. Depending on the cases that arrive at the location for autopsy, they approach the family and explain how the project works and what the donated brains can be used for.

On average, Leite says that around 60% of families approached agree to make the donation. “Brazilians are very open to donating their brains for science”, says the specialist, comparing the data to that of other biobanks around the world that carry out similar approaches. “It’s a painful moment, it’s a very difficult moment. I think this propensity that families have to want to contribute to science is very beautiful.”

The coordinator states that, normally, families who do not accept are based on religious reasons or do not know what the wishes of the person who died were in relation to the issue.

In the case of those who accept to donate, the researchers make available the results of the analyzes carried out on the loved one’s brain. “But the majority don’t come to us for the report. What they really want is to collaborate with science and help others”, says Leite.

The procedure shows, then, that it is not enough for a person to simply want their brain to be donated — and the biobank is sought after for this, according to Leite. At least, that is the current reality.

For the future, the project wants to open up this possibility. What prevents this from being done now is the need to have a team always present to receive donations and, more importantly, to talk to the donor’s family.

“We want to serve these families in the best way possible,” says Leite. “We need to have a team that is capable of answering the phone, that is capable of getting here before the family, so that we can welcome them very well at this time. So, we need to have very good logistics. It would involve a very large team and, consequently, a very large financial investment.”

And Maguila?

If it is not possible to actively make a donation, how did Maguila manage to donate his brain?

The legendary Brazilian heavyweight boxer’s interest in the subject began when Hilderaldo Bellini, defender and former captain of the Brazilian football team, donated his brain to the USP biobank.

“He [Maguila] He was very aware of things. I remember how positively surprised he was when Bellini donated his brain”, says Renato Anghinah, doctor and professor of neurology at USP. “He was very impressed by the family’s generosity. It was the first time he expressed that he would like to donate his brain.”

Maguila sought a doctor thanks to another former boxer. Éder Jofre had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and, according to Anghinah, when he reached his hands he was in a complicated situation. The USP doctor, however, raised another hypothesis for the symptoms: chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a condition caused by frequent shocks to the head.

The change in diagnosis and treatment resulted in improvements for Jofre, according to Anghinah. Then, requests began to appear for the doctor to treat Maguila.

At that time, Maguila had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s for more than a decade and was in a delicate situation. “I was already very weak, with a tube in my stomach. I couldn’t swallow, I had no appetite. I was wasting away”, recalls Anghinah.

The specialist, then, after being contacted by the family, began to treat the heavyweight and also concluded that his condition was chronic traumatic encephalopathy. With the change in diagnosis and treatment, Maguila’s health status improved.

According to Anghinah, around 15 days after changing treatment, Maguila was already swallowing. And, according to the doctor, if there was one thing the patient liked, it was eating. The former boxer reportedly said that, as soon as he received medical clearance, he would eat some feijoada. And he did so as soon as he could.

Finally, the donation of Maguila’s brain was possible because Anghinah has ongoing research into chronic traumatic encephalopathy with the biobank. This is also how Jofre’s brain ended up in the USP biobank.

The USP professor also says that Maguila said he was disappointed with the non-donation of the brain of Muhammad Ali, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Anghinah highlights that chronic traumatic encephalopathy does not only occur in athletes who suffer blows to the head. He says, for example, that he even assists victims of domestic violence who have developed the problem.

The specialist reinforces that it is important not only to donate organs for research, but also to save people who need transplants.

Other research

In addition to research on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, there are several research projects associated with the USP brain biobank, especially studies related to aging.

One of the projects currently underway looks at the brains of people over 90 who had good cognition and activity levels. Another, for the brains of people aged 18 to 65, to try to see possible signs of Alzheimer’s.

Sports personalities who donated their brains to USP

Adilson “Maguila” Rodrigues

Death: October 24, 2024 (66 years old)

Profession: Heavyweight boxer

Career:

- 77 wins (61 by knockout)

- 7 defeats (7 by knockout)

- 1 draw

Hilderaldo Bellini

Death: March 20, 2014 (83 years old)

Profession: Football player

Career:

- Captain of the Brazilian team that won the world championship in 1958

- Reserve for the team that won the 1962 World Cup

- Vasco da Gama icon

- Regarded as the first to make the gesture of raising the World Cup winner’s cup

Eder Jofre

Death: October 2, 2022 (86 years old)

Profession: Bantamweight and featherweight boxer

Career:

- 72 wins (50 by knockout)

- 2 defeats

- 4 draws