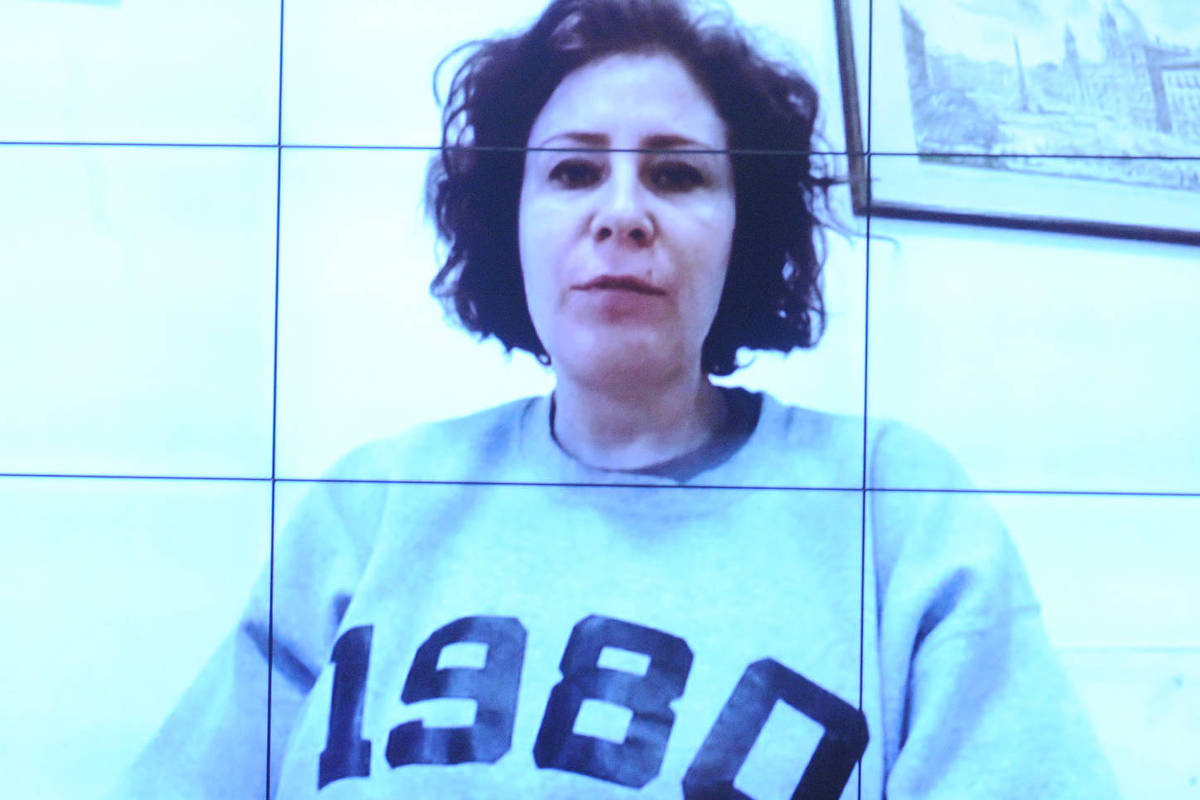

It is seven in the evening in Lagos, Nigeria. The sun has set and many of the city’s five million cars are driving, filling the streets with smoke. Shortly after, the national electrical grid is cut off: it is the turn of millions of diesel generators. The smog grows denser. , a former professional triple jump athlete, wants to close the window to breathe better, but outside the temperature exceeds 30 degrees. “There are a lot of exhaust gases, it can be terrible,” says the former athlete, who now collaborates in a campaign for clean air. Allergic reactions to pollution can trigger recurrent throat infections and attacks of pneumonia. Several of his relatives suffer from or have died from a lethal mixture of soot and sulfur produced by burning fuel. She achieved her silver medal at the 2006 Commonwealth Games because she decided to train out of town.

That the most populated city in Africa is suffocating in fuels with high sulfur content has to do with Europe: . Refineries divide crude oil into a series of products. The cleanest are sold locally, and the slag is exported: samples taken in Lagos contain sulfur levels of up to 800 parts per million, eight times the legal limit in Europe and North America. But the fact that these fuels are prohibited in Europe does not prevent this from being a transit zone.

Una, the data analysis consultancy Data Desk and several European regional media show that several ports in Europe, also in Spain, are points of passage, storage and mixing of components – such as gasoline, naphtha and other ingredients – that, together, reduce and produce this fuel with high sulfur content.

Last year, one in six barrels of oil shipped to Nigeria came from a blending plant in Antwerp, Belgium, that produced this more toxic type of fuel. Two-fifths of the products blended there came from the UK, with two refineries leading the way: one in Immingham, owned by Prax and Phillips 66, and another in Ellesmere, owned by Essar Oil. An anonymous source from Immingham confirms that the ingredients are so toxic, with sulfur levels of up to 10,000 parts per million, that they “cannot be mixed” within European limits. “It’s a horrible thing,” he says, “they send it to Africa, it’s a way to sell the waste product.” A Prax spokesperson notes that the company “complies with industry regulations and practices.” Phillips 66 and Essar did not respond.

Legal but “dishonest” practice

Exporting fuel with high sulfur content is not illegal. But it is “a dishonest practice,” says Martin Blunt, an oil markets researcher at Imperial College London. “Refineries would have to pay to remove the sulfur, so a cheaper way is to take a fuel with a medium level of sulfur, and from that create one with a low level and another with a high level, and sell them in different markets,” he says.

The Data Desk data comes from two maritime traffic monitoring tools for petroleum products, and both show that the ingredients also pass through Spanish ports (serving as a connection between the United Kingdom, where crude oil is refined, and Nigeria) to generate this fuel. more toxic, known in the industry as “African quality fuel” or “jungle juice.” Above all, through the ports of Barcelona and Huelva. This transit does not in itself imply that the “juice of the jungle” is produced, but the research indicates that it is a strong indicator, as is the import into these ports, from Libya, of an essential component for this: gasoline. pyrolysis or pygas. Sources from the Ministry for the Ecological Transition point out that this year there have been no fuel oil exports to Nigeria, but data from Data Desk indicate that there have been shipments of ingredients from Spain to the African country: until October they have reached more than five million barrels, more than triple that in 2023. In 2024, 20 ships have been registered from Spain, compared to nine from the previous year.

One of the companies in Barcelona that are listed as receiving these ingredients, which has a terminal in the Catalan capital and another in the port of Tarragona, categorically denies that fuel with high sulfur content is mixed or stored in its plant. Meanwhile, a person who has worked for 20 years in the company’s operations department, who prefers to remain anonymous, sees it as “feasible” that something like this is being done: “Inside the terminal they do what they want, they have always done it.” ”, he states.

For some time now, Spanish ports have seen traffic in these ingredients increase. Especially since two European states, Belgium and the Netherlands, have placed limits on sulfur levels in the fuels they export. But refiners and traders are adapting quickly: Data Desk analysis suggests that where it has been banned, there have quickly been route changes for ships.

Lack of regulation

Only high-level bans in the EU and the UK can stop the flow of dirty fuel to Africa, according to Oliver Classen of Public Eye, a Swiss group that first investigated this trade in 2016. Until there is a framework European Union that addresses the problem, suppliers will continue to respond to demand, says a Vitol customer, who speaks on condition of anonymity: “Mixtures according to the specificities of each country. “If someone asks for water, you’re not going to give them champagne.” A Trafigura spokeswoman says the company guarantees that the products it supplies “meet the contractual and legal specifications required for each jurisdiction.” For its part, a Vitol spokeswoman says: “Only the government and regulatory authorities of a given market can determine what fuel is consumed in that market, so only they can be held responsible.”

Until May 2023, many of the shipments from British refineries went to the Netherlands. When the Dutch government banned dirty fuels, exports shifted to Belgium: between 2023 and this year, more than three million barrels of “CC,” or “catalytically cracked” gasoline and naphtha — typically associated with a high sulfur content — left the United Kingdom bound for Sea-Tank K700B, a mixing unit in Antwerp. This fall, Belgium introduced its own restrictions and shipments to this plant have decreased. Since then, there have been shipments of ingredients for “jungle juice” that have gone to Latvia or Barcelona.

Without waiting for Brussels to take action, Nigeria last month introduced a stricter sulfur limit of 50 parts per million. But change is slow. Baskut Tuncak, former UN special rapporteur on toxic substances and human rights, warns that European countries could be breaking international law by allowing companies to export dirty fuels, referring to the 1998 Bamako Convention, signed by 17 African countries, including Nigeria.

And, the product will find its way to other African states if governments do not take action, says the Vitol customer. “No one wants to ship this stuff, but economics is the reason this happens. The solution has to be political,” he points out. Meanwhile, Ayomide Jones, another athlete from Lagos, continues to have trouble breathing. “I have stopped running at night, when there is traffic, because I feel bad afterwards. “We are killing ourselves due to lack of policies and regulation.”

This article has been developed with the support of Journalism fund Europe