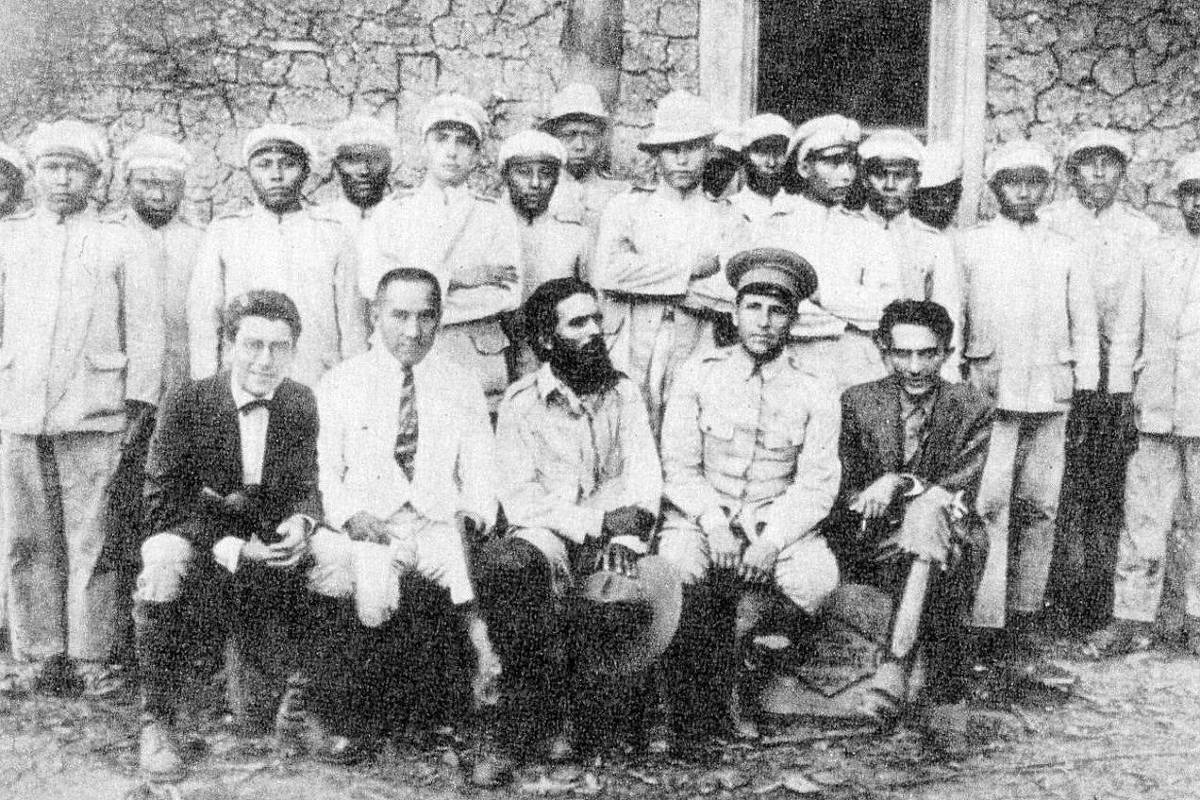

The Coluna Prestes march, which began 100 years ago, became known by the nicknames undefeated and invincible. But they faced setbacks in the three incursions they made through Bahia, dealing with the strength of colonels, the wrath of the jagunços and the resistance of the country people.

The movement was started on October 28, 1924 by the 1st Railway Battalion of Santo Ângelo (RS), which joined troops from other states in a march that would cover 25 thousand km across the country in three years. The military challenged the political regime of oligarchies and the

In the early 1920s, Bahia was experiencing a period of political turbulence. The election of José Joaquim Seabra to the government encouraged the opposition, who announced a march by colonels from the backlands to take the capital – the episode would become known as the Sertaneja Revolt.

decreed intervention, but paved the way for Seabra’s inauguration. In office, the governor signed the “Lençóis Agreement”, amnestying the rebels and handing over municipal administrations to the colonels.

The agreement gave muscle to the political leaders who dominated the backlands of Bahia, which was experiencing a period of prosperity with diamond and gold mining, rubber extraction and the implementation of railways.

Among them was Horácio de Matos, a colonel who gained ground in – where he dominated 11 cities, including Lençóis – anchored by a paramilitary group. With such political influence, he rose to be called “governor of the backlands”.

Alongside them, landowners called colonels, such as Franklin Lins de Albuquerque, Abílio Wolney and Deocleciano Teixeira, formed a kind of belt in the backlands of Bahia.

With , President Artur Bernardes offered support in the fight against the insurgents. Thus, military units were created such as the Lavras Diamantinas Patriotic Battalion, made up of 1,500 men from among jagunços and soldiers from regular troops.

“The colonels are presented as legalists, but it was an exchange relationship. The paramilitary groups are incorporated into the regular forces and participate in the fight against the column in exchange for ammunition, weapons and ranks”, explains historian Flávio Dantas Martins, professor at the Federal University from Western Bahia.

The march entered Bahian territory for the first time in September 1925, after crossing the Carinhanha River. It covered a small strip of the western region of the state, returning to

The soldiers would return in February 1926, when, surrounded by government forces, they decided to cross the São Francisco River. In the midst of a historic flood, they crossed the riverbed in canoes, leaving most of the horses behind.

In Bahia, around 1,200 men trekked through areas of caatinga, opening trails and facing adverse conditions. They imprisoned residents to serve as guides and attacked police garrisons.

They crossed Chapada Diamantina without obtaining support in the cities and towns, which emptied before the arrival of the march. They avoided clashes with government troops, but left a trail of looted and burned locations.

The march left Bahia on April 19 and encountered loyalist battalions in Encurralado, Prestes led the military maneuver that would become known as the “Hungarian loop”, making the march go in the opposite direction, parallel to the path taken, deceiving the enemies.

With no hope of success in the march, the rebels returned to Bahia on May 1, beginning a journey to reach Goiás, cross Mato Grosso and head towards But the path would not be easy.

“The jagunçada redoubled the violence of the attacks”, wrote Lourenço Moreira Lima, secretary of the Column, highlighting a scenario of forced march, with enemies hot on their heels.

The main targets were the potreadas, tactical groups that moved away from the column to get food and mounts.

João Alberto Lins de Barros, one of the column commanders, recalled the ambushes faced during this period: “We could not cross a small village, an important farm, or even camp in a good water, without paying blood tribute”.

One of these ambushes was in Canabrava do Gonçalo, now Uibaí (500 km from Salvador). On May 13, 1926, the ragged march, with around 300 fighters, entered the town with their red scarves. They were repelled by five armed men, who were lying in wait at the top of a mountain.

Days before, the column had been surprised by an attack in Mucugê. The shots came from various parts of the city, including the cemetery, resulting in casualties. The episode would become known as Fogo de Mucugê or Combate da Volta do Morro and is seen as a point of weakening of the column, which would have a base in the city to resupply and regain strength.

But it wasn’t just raids that marked the march in Bahia. In the city of Central, young Francisca Ferreira Rocha went to the column’s camp and complained to General Miguel Costa after having ten mares and a box of jewelry looted. Intrigued, he ordered the return of the animals, as Francisca herself says in a statement to researcher Mariene Martins Maciel.

“The country people are seen as simple people who were manipulated by the colonels. But, from the perspective and memory of the participants themselves, they are defending their territory from invaders”, says historian Flávio Dantas Martins.

The Prestes Column would leave Bahia in July 1926 towards Bolivia, being pursued to the border by Horácio de Matos’ men. in the neighboring country, a period in which he approached the

The colonels strengthened themselves in the game of political forces in Bahia. Brazilianist Eul-Soo Pang, in “Coronelismo e Oligarchias”, points out that local chiefs began to bypass governors in political and military matters, shaking the backbone of the oligarchic system.

The implosion of the First Republic would come in 1930, with the tenentist revolution led by . The new government would arrest Colonel Horácio de Matos, murdered five months later by a police officer on the streets of Salvador. It was the end of an era in the backlands of Bahia.