Saint Helena Mount

Despite having only spent one day on Mount Saint Helena, the effects of rodents on the recovery of biodiversity are still noticeable today.

Forty years after the devastating eruption of Mount St. Helens, an experimental introduction of moles demonstrated deep and lasting effects in the recovery of local ecosystems.

The initiative, designed to restore soil health and promote plant growth, demonstrates how even small interventions can produce long-term ecological benefits.

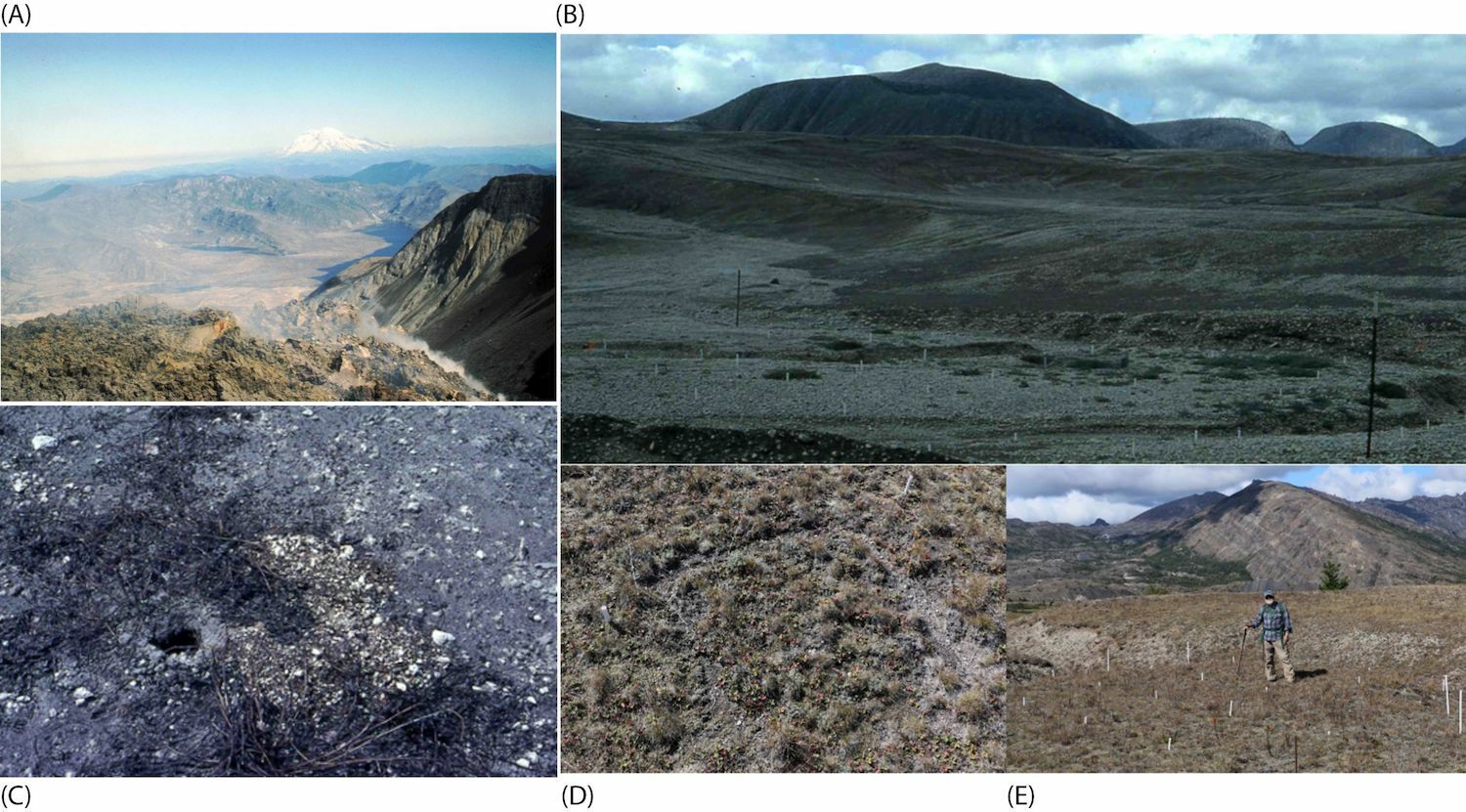

The 1980 eruption destroyed all life within miles, leaving the land barren and covered in ash and pumice. In 1982, scientists hypothesized that moles, often seen as pestscould help with recovery, bringing buried soil, rich in bacteria and fungi, to the surface.

One recently published in the magazine Frontiers in Microbiomes highlights that the brief presence of rodents continues to influence the microbial composition of these plots four decades later.

This idea was tested by introducing specimens of the northern mole gopher (Thomomys talpoides), a species of local rodents, in two plots covered with pumice during just 24 hours.

“We thought they would take old soil, move it to the surface, and that would be where the recovery would occur,” he explains. Michael Allena microbiologist at UC Riverside and co-author of the study. The results were transformative.

In 1989, these plots, once lifeless, supported 40,000 plantswhile the untouched areas remained mostly barren.

The key to this recovery was the soil microbial communitiesparticularly mycorrhizal fungi.

These fungi establish symbiotic relationships with plant roots, facilitating the absorption of nutrients and water and providing resistance against pathogens. Without these microscopic allies, most plants have difficulty establishing themselves in nutrient-poor environments.

The introduced areas present greater biodiversity and resilience compared to nearby regions where rodents were absent, explains the .

The study also examined how microbial activity influenced plant growth in two contrasting forest environments. In ancient forests covered in volcanic ash, mycorrhizal fungi helped trees grow quickly by recycling nutrients from fallen needles.

In contrast, a nearby clear-cut forest – devoid of trees and soil fungi – remains largely barren, underscoring the critical role of subterranean microbial networks in ecological recovery.

The main author of the study, Mia Maltzhighlights the importance of recognizing the interdependence of the visible and invisible components of ecosystems. “We cannot ignore the role of microbes and fungi to help ecosystems recover from disasters,” he said.