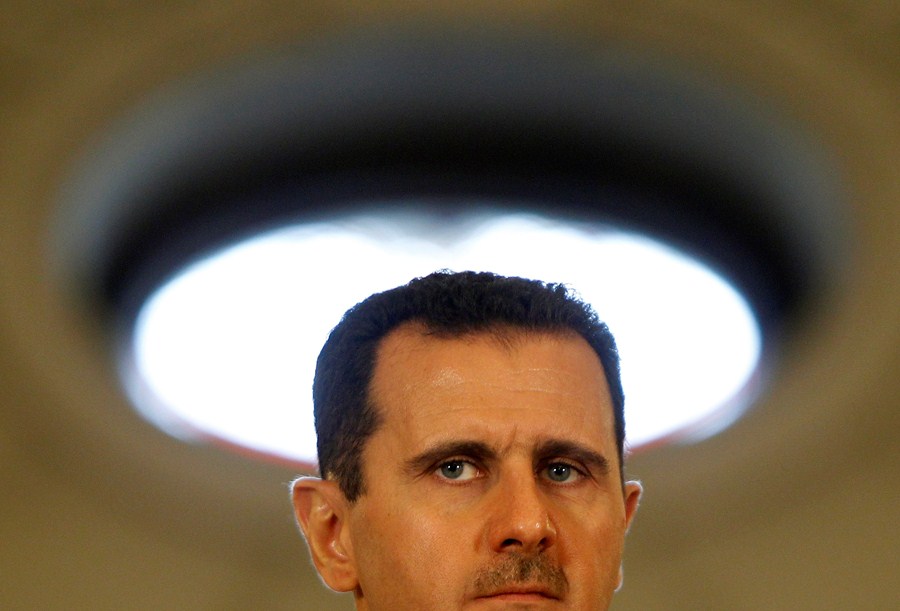

Bashar al-Assadthe Syrian president who inherited power in 2000 with promises of reform but brutally repressed opponents in a war that cost hundreds of thousands of lives, has been , according to state television.

Assad, according to several reports, fled from Damascus as opposition forces led by Islamists entered the capital and put an end to more than half a century of rule by the Assad family.

Continues after advertising

Russian news agencies reported on Sunday afternoon (Brasília time) that Bashar al-Assad and his family arrived in Russia and received asylum “for humanitarian reasons”.

A report by Reuters and a non-governmental group tracking the war in Syria suggested that Assad’s plane left an airport in the Syrian capital shortly before rebels took control.

Assad’s transformation from a potential Western ally into a ruler who has responded ruthlessly to peaceful protests against his rule has surprised many. Since the use of chemical weapons against civilians until widespread tortureAssad faced serious accusations during the Syrian war, but managed to survive the unrest thanks to strong support from Moscow and Tehran.

Continues after advertising

During his final days in power, Assad’s supporters were reluctant or unable to support him in the face of a shocking military advance that Syrian rebels began about 10 days earlier.

How Brazil positions itself in the face of Assad’s fall

The Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that it is following the escalation of conflicts in the Syrian civil war with “concern”.

In a note issued before confirmation that Assad had left Syria, Itamaraty reported: “Brazil supports efforts for a political and negotiated solution to the conflict in Syria, which respects the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country.”

Continues after advertising

Unlikely ruler

Bashar Hafez Al-Assad was born on September 11, 1965, in Damascus, the third child and second son of Hafez al-Assad e Aniseh Makhlouf. The family’s roots were in the Alawite minority, a small part of the school Shia of Islam.

Assad’s father was an air force officer who helped lead the socialist Baath Party’s takeover of government in 1963 before taking power himself in a bloodless military coup in 1970.

Assad grew up in the capital and graduated from Damascus University medical school in 1988, according to his official biography. Fluent in English, he was receiving advanced training as an ophthalmologist in London in 1994 when Bassel, his father’s first choice for president, died. Assad returned home to be prepared to lead Syria.

Continues after advertising

Assuming authoritarian rule at age 34, the tall, suave Assad promised to follow a path of economic reform and liberalization.

Young image

Many Syrians, as well as Arab and Western leaders, were willing to give Assad a chance, in part because he projected a youthful image and seemed willing to loosen his grip on the government.

Assad crossed sectarian lines by marrying Asma al-Akhras, a Sunni Muslim and daughter of Syrian expatriates who grew up in Britain. They had two sons, Hafez, born in 2001, and Kareem, born in 2004, and a daughter, Zein, born in 2003.

Continues after advertising

The couple’s populist touch contrasted with Hafez’s austere approach. At home, Asma, a graduate of King’s College London who worked for JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York for three years, advocated for women’s rights and education. Outside, the Assads were welcomed with a red carpet on official visits to Arab and European countries.

In his first months as president in 2000, Assad ordered the release of 600 political prisoners, some of whom were members of the banned Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni Islamist group.

Assad said Syria needed constructive criticism, a radical notion at the time in a country that has jailed political opponents. Intellectuals openly called for greater civil liberties and democratic reform. The first months of Assad’s rule were, optimistically, dubbed Damascus Spring.

Change of tone

After Assad’s first year in office, however, the government extinguished the pro-democracy movement, putting its leaders in prison. Accusations ranged from trying to change the constitution to inciting sectarian conflict.

In 2005, opposition groups came together to issue a declaration demanding free parliamentary elections, a national conference on democracy, and an end to emergency laws and other forms of political repression. Assad responded by arresting its main signatories.

Then street protests began in early 2011, at the beginning of Arab Spring. At that time, Arab heads of state in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen succumbed to uprisings that swept North Africa and the Middle East.

A violent reaction from Assad to protesters has escalated the conflict into a protracted civil war and emboldened radical groups, including the Islamic State, or ISIS.

Determined not to join the list of deposed Arab rulers, Assad chose to use brutal force, including bombs, torture, and chemical weaponsto suppress dissent, according to the US and other Western nations.

He benefited from the fact that the opposition was fragmented into hundreds of groups, mainly Islamists, which the US and its allies supported only cautiously. The former president Barack Obama and his successor, Donald Trumpordered waves of airstrikes against Assad’s strongholds, but had little appetite for deeper intervention.

chemical weapons

In 2013, the US blamed Assad for the deaths of more than 1,400 people near Damascus in an attack that used sarin gas.

The Assad government blamed the attack on Islamic extremists but agreed to a US-Russian plan for international monitors to take control of Syria’s chemical weapons.

About that, Iran and Russia supported Assad with money, personnel and weapons.

A turning point in the war came in 2015, when Russia sided with Assad and, together with Iranian forces, helped Assad halt the advance of opposition troops and begin recapturing territory.

Forces loyal to Assad, with help from Russia, Iran and the Lebanese militia Hezbollahmanaged by 2020 to confine the territory controlled by militant groups to less than half of the country, replacing total war with sporadic fighting.

In 2021, Assad secured a fourth term as president in an election that international observers considered neither free nor fair.

The insurgent threat to Assad’s government suddenly resurfaced late last month, beginning with a surprise advance by opposition fighters into the city of Aleppo. The rebellion was led by Hayat Tahrir al-Shama former al-Qaeda affiliate designated a terrorist organization by the US and others.

“Our goal is to free Syria from this oppressive regime,” he said Abu Mohammad al-Jolanithe leader of the group also known as HTSto the New York Times. He occasionally uses his real name, Ahmed Al-Sharaa.

During his final days in power, Assad ordered his army to retreat to defend Damascus, essentially ceding much of the country to the insurgents. His last-ditch attempts to stay in power included indirect diplomatic approaches to the US and the president-elect Donald Trump.

Iran and Hezbollah, which had strengthened the regime at the start of the civil war, were now significantly weakened by attacks carried out by Israel in its conflict with Iran.

Assad’s fall ultimately eliminates one of Iran’s key allies in the Middle East and represents a major blow to Tehran’s influence in the region.

Many in neighboring Lebanon have blamed Assad for his support of Hezbollah and accused him of having a role in the assassination of senior officials, including former prime minister Rafiq Hariri in 2005.

A displaced society

More than 600,000 people had been killed in the Syrian civil war until March 2024, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based group that closely monitors the conflict. More than half of the pre-war population of 23 million has been displaced, either to other regions within Syria or to other countries, according to the United Nations. This made the crisis one of the most serious refugee crises since the Second World War.

“Assad is the man who presided over the end of modern Syria,” said Paul Salem, president of the Washington-based Middle East Institute. “The fierce attacks on protesters have forced the discussion about political reform to turn into an armed war, forcing people to take up arms and giving the advantage to radicals who have extensive combat experience.”