The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, oil on canvas by John Martin (1821)

In the vast network of historical and scientific debates, few enigmas have aroused as much fascination as the exact date of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. A recent study reopens the controversy.

The date of the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuviuswho in 79 AD destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneumcontinues to be the subject of study and controversy among archaeologists, historians and experts in natural sciences.

One recently published by the Archaeological Park of Pompeii reopens this discussion with a critical and multidisciplinary approach, questioning certainties accepted so far.

The traditionally accepted date for the tragedy, 24 August at 79 dCoriginates from the correspondence of Pliny the Youngerthe only contemporary witness who documents the catastrophe in his letters.

However, recent investigations revealed inconsistencies when transmitting this information, please note.

According to the report, philological studies have shown that the original manuscripts present variations — and some misinterpretations led to alternative dates, such as October 24th or even Novemberall based on assumptions without solid foundations.

In the new study, the archaeologist Gabriel breeding bar and his team emphasize that the original manuscript tradition unequivocally indicates August 24th.

However, this data, although firm in the texts, does not necessarily align com as archaeological evidence. Since the 18th century, finds in and around Pompeii have suggested the possibility of an autumnal eruption, creating fertile ground for academic debate.

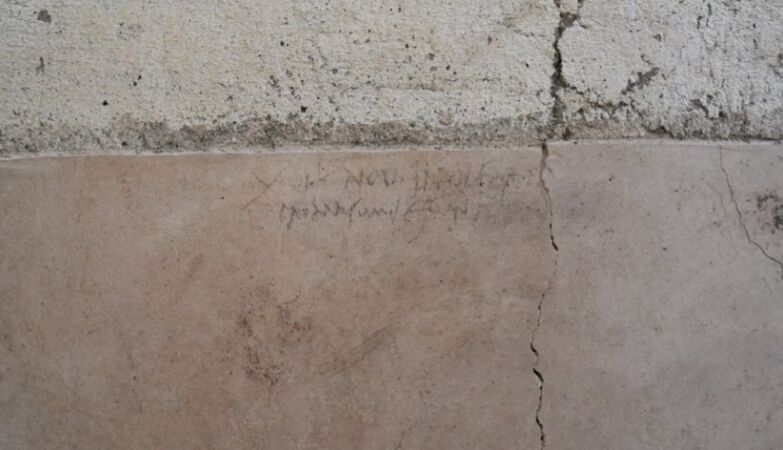

Among the elements that fuel this controversy are discoveries botanical, numismatic and architectural. For example, in 2018, a charcoal inscription dated October 17th at the Garden House of Pompeii.

Pompeii Archaeological Park

Charcoal inscription found in Pompeii mentions date in October

This fact has led some researchers to suggest that the eruption could have occurred after this date.

However, the Pompeii Archaeological Park report presents a study of experimental archeology which demonstrates that these inscriptions may have lasted until ten monthsrejecting its use as conclusive proof of an autumnal date.

In the same way, the presence of fruits such as chestnuts and pomegranatestypical of autumn, in archaeological strata from 79 ADwas used to support the hypothesis of a late eruption.

However, experts from the Archaeological Park argue that these findings should be interpreted in broader contextsconsidering factors such as Roman agricultural and storage practiceswhich allowed the conservation of products for long periods.

An intriguing example is the coexistence of peachesassociated with summer, and chestnuts, typical of autumnin the same strata.

Likewise, soil and organic residue analyzes made it possible to reconstruct Roman agricultural practices, enriching the historical context, but not resolving the problem. dating dilemma.

According to the study authors, these investigations open new perspectives, but require a multidisciplinary approach that integrates archaeological, climatic and cultural data.

The report concludes that the debate over the exact date of the eruption should not focus on choosing between different dates proposed by manuscript tradition or archaeological finds.

Instead, raises a more fundamental question: Is there enough evidence to refute the date of August 24th transmitted by Pliny the Younger? So far, the answer seems to be negative.

The researchers therefore advocate a more cautious and methodological approach — avoiding premature conclusions based on isolated or misinterpreted evidence.

More than finding a definitive answer, the objective of the study is to provide a solid basis for a rigorous and open academic debatethe authors conclude.