When Ephraim Trembly found his brother in rural Maryland, John had already been dead for three days.

According to their father, John Trembly Sr., how he died remained unclear, since John’s body was so decomposed that they could only identify him from a tattoo. The coroner found , so it stood to reason that John had overdosed, his father said. But the autopsy also showed something else, something more unusual: At 20 years old, John’s cardiovascular system had been destroyed.

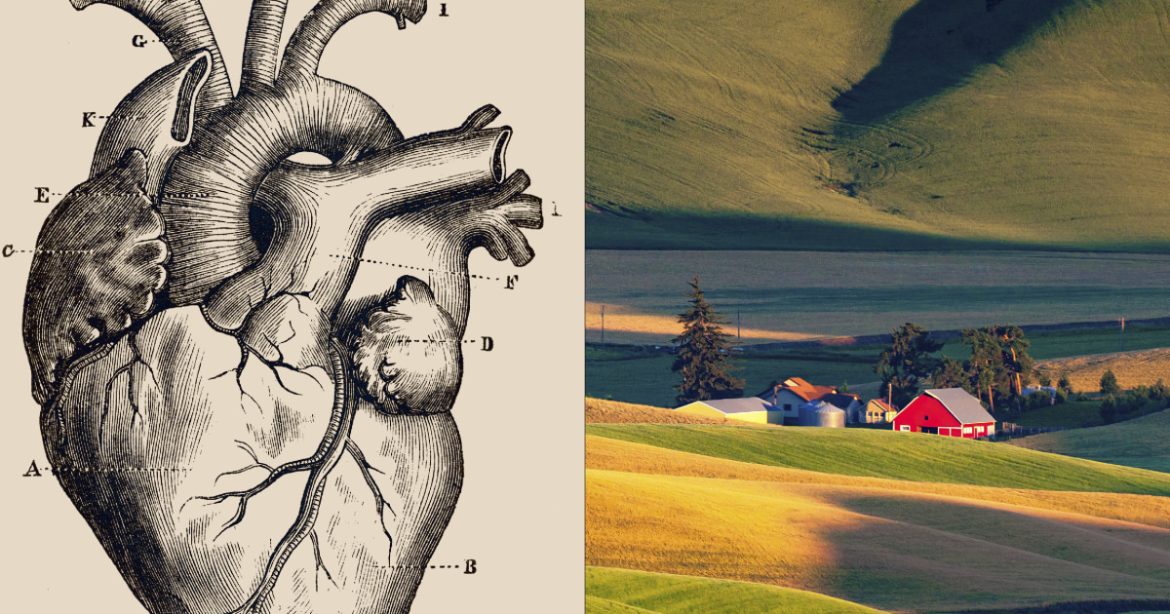

Before his death last year, John had spent most of his life in Terra Alta, West Virginia, a town of fewer than 1,500 people.

A reside in rural areas, and on average they live than their urban counterparts, largely due to . And this disparity widened between 2010 and 2022, driven by a 21% increase in cardiovascular deaths among working-age rural adults, according to research published last month in the .

This is the first national analysis of rural cardiovascular health during Covid-19, said Dr. Rishi Wadhera, a cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and the senior author of this study. While heart disease and stroke deaths had been decreasing in both rural and urban communities before 2019, they shot up with the arrival of the pandemic in 2020, reversing .

“It is inexcusable for young adults to be experiencing an increase in cardiovascular death rates anywhere in this country,” Wadhera said.

Dr. Chris Longenecker, director of the global cardiovascular health program at the University of Washington in Seattle, said the findings aren’t necessarily surprising, as cardiovascular mortality has always been worse in rural areas due to a collision of factors, including drug use, poor health and limited access to care. But the study renews questions about what’s driving these widening disparities and what, if anything, can stem the bleeding.

“Nobody wants to see their son at 20 years old pass away, when they have their entire life in front of them,” Trembly Sr. said. “It’s really just not fair.”

Drivers of the rural-urban divide

In Wadhera’s study, he and his team examined death certificate data by age for over 11 million adults. Between 2010 and 2022, cardiovascular deaths increased among 25- to 64-year-olds but decreased among people ages 65 and up. In rural communities, those increases occurred at a faster rate and the decreases at a slower rate than in their urban counterparts.

On some level, these disparities come down to differences in underlying risk factors. Hypertension, diabetes and obesity have all been rising among younger adults over the past decade, with rural areas disproportionately affected, said Longenecker. That’s tied to systemic issues, including lower health education, higher unemployment and not having easy access to gyms and fresh food.

Small towns and rural areas have also been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis, not only worsening people’s economic conditions but also to heart disease deaths, according to Dr. George Sokos, the chair of the cardiology department at West Virginia University. Stimulant overdoses — from methamphetamine and cocaine — have also been on the rise, increasing between 2012 and 2022.

John used to clean rental houses during the day and businesses at night, his father said. To keep up with the grueling schedule, he turned to methamphetamine to stay awake and work faster. When his girlfriend was in the hospital for a month, John took on her cleaning job as well, all while driving two and half hours every day to visit her.

“He was keeping up with the workload of two people,” the senior Trembly said. “His boss had no idea she was in the hospital.”

However, meth is also heart disease and stroke. Chronic use likely ravaged John’s cardiovascular system and perhaps contributed to his death, his father said.

These challenges are all exacerbated by limited access to health care in rural communities.

“We have a difficult time attracting primary care physicians in our state,” Sokos said, noting that makes it more difficult to prevent cardiovascular disease or intervene early. And that’s not to mention the to manage these conditions and treat complex cases. “We’re unable to get to some of these younger patients earlier enough,” he added.

The Covid pandemic further magnified these issues, with Wadhera’s study finding that cardiovascular mortality rose by 3.6% in urban areas but by 8.3% in rural areas between 2019 and 2022.

“The pandemic is an external stressor that just made all of those underlying social determinants worse,” Longenecker said.

For example, skyrocketed , as treatment resources were disrupted and people turned to drugs as coping mechanisms. With hospitals stressed by Covid patients and, in rural areas, shutting down , preventive screenings , as did .

“It wasn’t just disruptions because hospitals were strained,” Wadhera said. “Many people just feared coming into the hospital or health care settings to receive care.”

Telehealth was supposed to bridge this gap, but evidence suggests that it actually may have , as rural communities without internet access were left behind. Indeed, of West Virginians don’t have access, and of those who do, less than half have high-speed internet.

“My patients will drive to the gas station parking lot, hook up to the internet, and do a telehealth visit from the phone,” Sokos said. “The patients want the care; it’s just they’re unable to get that.”

Solutions ahead

In rural America, reversing the rise in heart disease and strokes isn’t a question of innovation.

“We’re doing cutting-edge medical things here; we’re doing robotic surgery that no one else in the country is doing,” Sokos said. “But what’s just as important is getting to the ground and getting to the patients to deliver basic care.”

West Virginia University has tried to tackle some of these issues by hiring more physician assistants and nurse practitioners, as well as sponsoring visas for foreign-trained doctors that come to the state, said Dr. Jeremiah Hayanga, a cardiothoracic surgeon at WVU.

During the pandemic, the university also stepped in to to maintain health care access across the region, Hayanga said.

For Longenecker, any path forward requires a community-driven approach. To that end, he heads a that takes lessons from health care delivery around the world and seeks to apply them to rural communities in the U.S.

One project involves training people who have received addiction treatment to go into the community and do tests among people who use meth.

Another supplies ultrasound machines to community health workers so that they can check patients for heart disease.

“They’ve been using this approach in Uganda” to identify cases early and prevent progression, Longenecker said. So, he continued, why couldn’t it work on Native American reservations as well?

In general, the idea is to bridge geographic barriers and bring cardiovascular care closer to where people are, Longenecker said. African countries have done that to great effect, providing HIV care in community settings, and in the United States, blood pressure services are increasingly being provided in .

“What is rural America’s barbershop equivalent?” Longenecker asked. “Hypertension care is not rocket science; you can really do a lot of it in the community,” whether that’s the library, church or someplace else.

At the heart of this work is active engagement with rural communities, he said. After all, the experiences of people in the Cherokee Nation will be completely distinct from the Alaskan frontier, or from Black Americans in the rural South — a region sometimes called the . One key limitation of Wadhera’s paper is that it doesn’t examine race and ethnicity data, or geographic differences among states. But that’s where the work on the ground comes in.

“Can we do actual rigorous implementation science with rural communities? To say, how can we structure health services delivery differently in your community to address these disparities?” Longenecker asked.

An uncertain future

Better health care delivery will certainly help address rural cardiovascular disparities but won’t necessarily address the underlying socioeconomic drivers.

“This is previously a community that’s steeped in coal mining,” said Hayanga, noting that West Virginians are now struggling as those jobs have disappeared without much to replace them. “We need to support the local community so that they are able to make a living.”

Still, both Hayanga and Longenecker have hope, seeing new interest and research funding into rural-urban disparities, as well as a greater national spotlight on this issue.

“In Congress, you have many of these more rural states represented by the Republican Party, which is now in power,” Longenecker said. “I’ll be curious to see how this influences policy decisions around rural health.”

But any change will come too late for John Trembly Sr. and his late son.

“What can we do? How can we help? All you can do is just stand back and watch,” he said. “It would be nice to have a way where we could help our loved ones more.”