Clay tablet with the geometric diagram of a triangle, with the (wrong) calculation of the area of the triangle.

Have you ever done something so stupid on your homework that it was preserved in stone and analyzed by researchers thousands of years later? Well, someone in Babylon did.

More than a memorial to a math error, a stone tablet shows how Babylonians were advanced in your time.

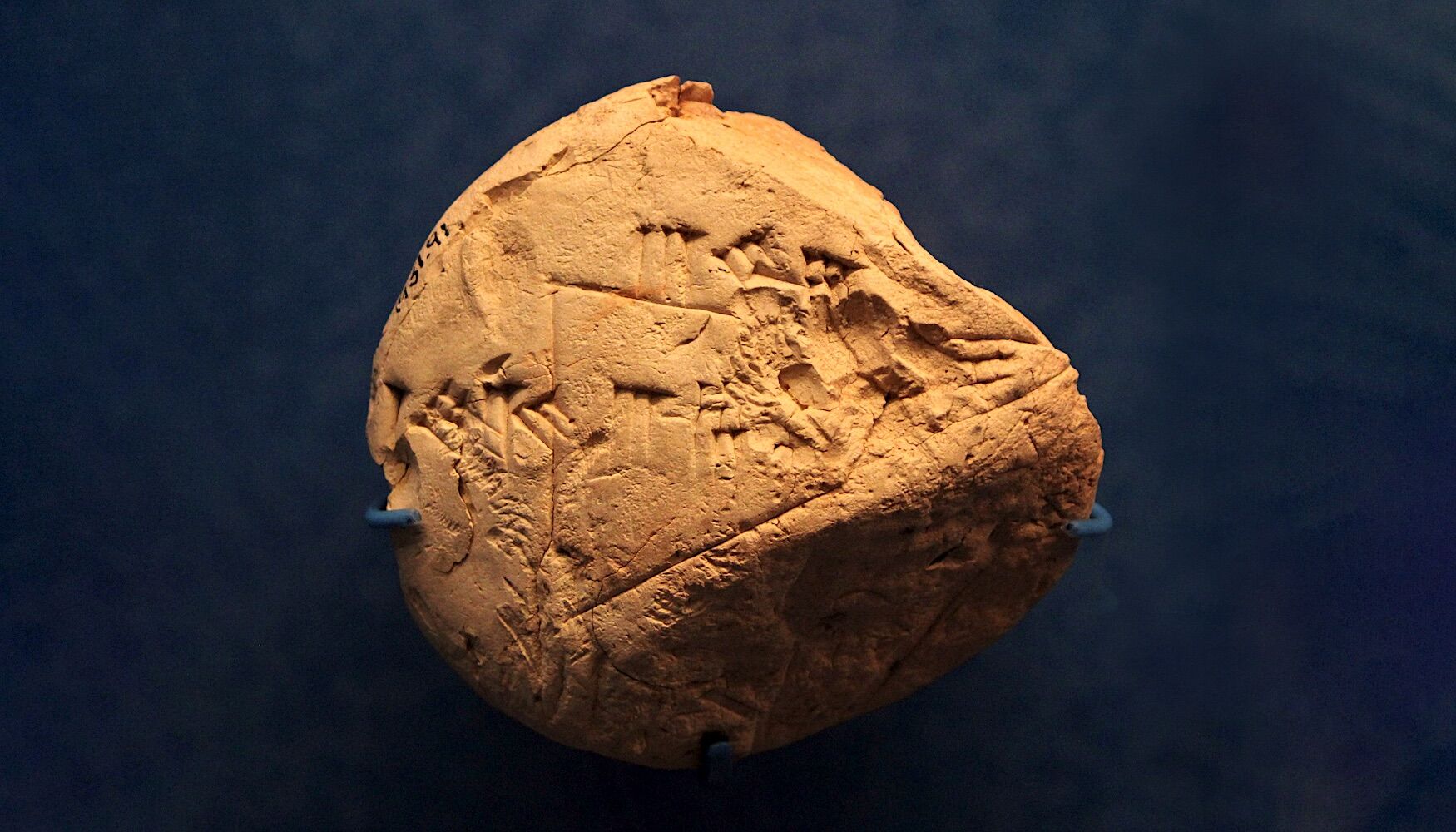

The artifact in question is a small round clay tablet about 8.2 centimeters in diameter. Unearthed from the archaeological site of Kish, in modern-day Iraq, this tablet is now in the collection of the University of Oxford.

It is found among about two dozen similar tablets, believed to be all traces of mathematics teaching in ancient Babylon.

The clay tablet is written in cuneiforma writing system used in several languages of the ancient Near East.

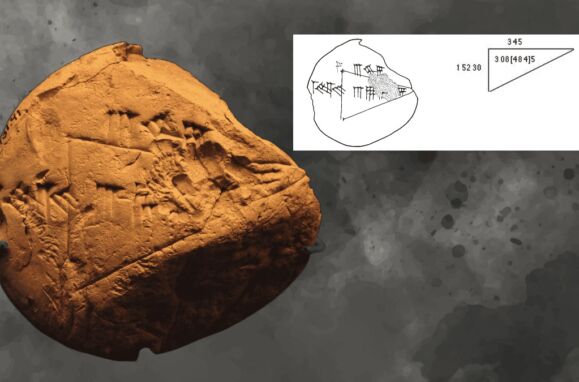

The student’s task essentially consisted of calculate the area of a triangle. The student was given the height of the triangle (1.875) and the base (3.75). To obtain the area of the triangle in question, it is necessary to multiply the base and height and divide by 2, that is: (1,875 x 3,75) / 2 = 3,515625.

The number is long, but the formula is very simple. The Babylonian student, however, obtained 3.1468 — the wrong solution.

The error appears to have arisen due to the sexagesimal house displacement of a part of an intermediate calculation, notes the teacher Eleanor Robsonprofessor at University College London and researcher at the Ashmolean Museum, in one on the cuneiform stones of Kish.

The table (on the left) and a diagram of the mathematical problem (on the right).

Babylonian mathematics was very advanced for its time. The Babylonians used a base 60 number systema trace of which persists to this day in our measurement of time – 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour.

Remarkably, highlights the , Babylonian scholars understood the Pythagorean theorem more than a millennium before Pythagoras: they already knew that the sum of the squares of the two shortest sides of a right triangle is equal to the square of the hypotenuse.

A durability of clay tablets ensured that these ancient records survive to this day, offering important knowledge about the beginnings of human civilization.

The student’s calculation error is trivial in itself, but has substantial historical significance. Shows how the ancient Babylonians made the transition from oral transmission to written transmission of knowledge, a change that began around 3500 BC in Kish.

This passage allowed preservation and dissemination of knowledgelaying the foundations for future educational systems.

Furthermore, the error humanizes the clumsy student Babylonian. We all make mistakes at school, and this reminds us that the learning process, with its trials and errors, is a timeless aspect of human development — one thing that hasn’t changed: we’ve all had difficulty mastering math at times. .