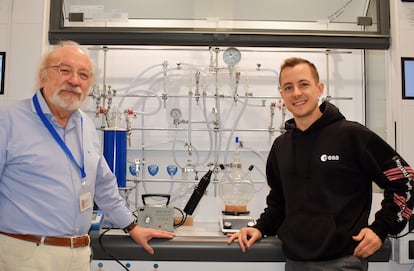

The geologist says, still amazed, that he and his colleagues have created “a protoworld” in their laboratory, just 1,500 meters from La Concha beach, in San Sebastián. It sounds transcendental, and it is, but it is a small transparent container, three liters, in which they have basically put a glass of water, methane, nitrogen and ammonia, adding electrical discharges to imitate the wild environment of the primitive Earth. It is another version of the famous experiment by , a 22-year-old American chemist who in 1952 found it easy to create the basic bricks of living beings in that primordial broth. García Ruiz, however, has encountered a major surprise. Also in his bottle, some structures that he considers the anteroom of life. “It’s amazing,” he proclaims.

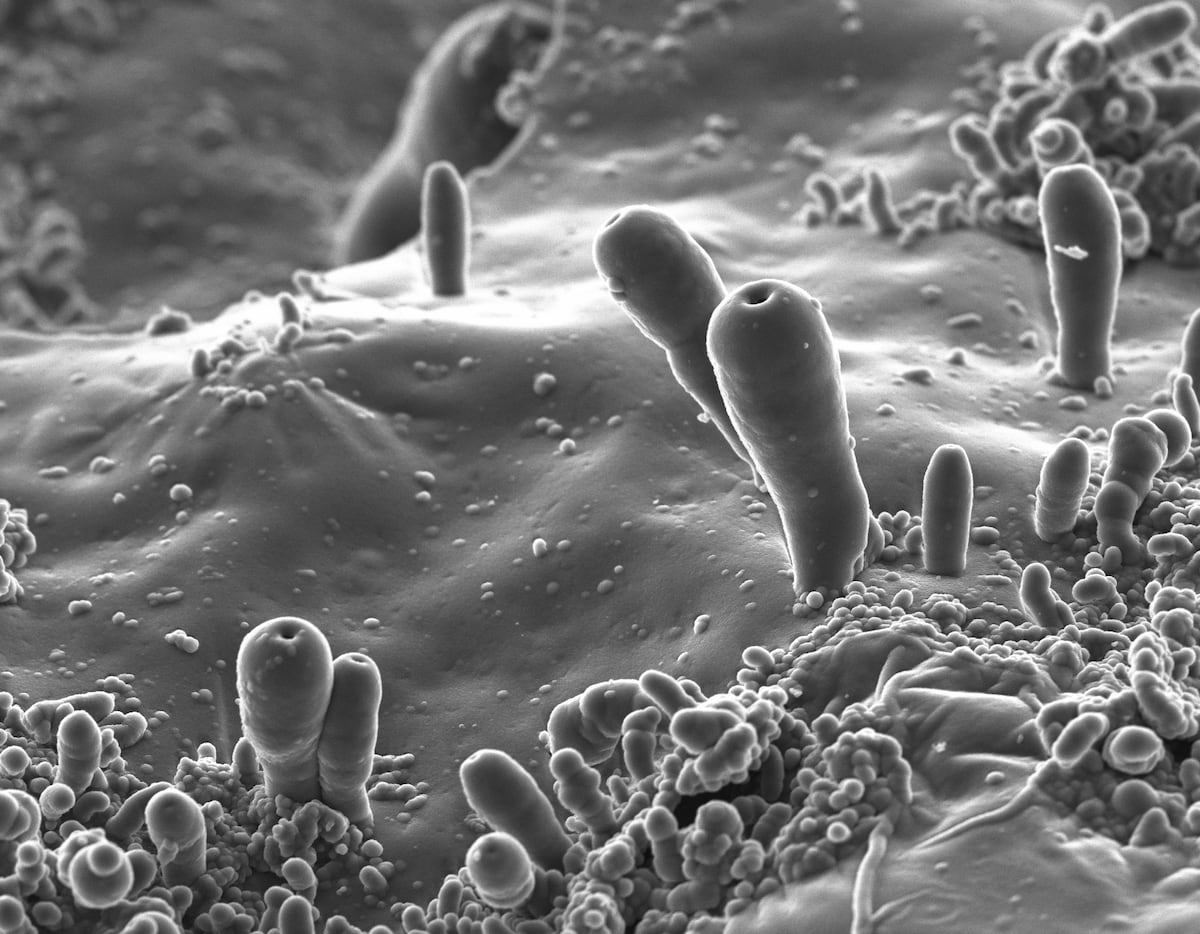

The researcher, born in Seville 71 years ago, says that his experiment barely lasted two weeks. Soon a surface layer formed, like cream on milk, and the clear water turned yellowish brown. The microscope images are disconcerting. A multitude of tiny curvilinear structures appear, which any observer would attribute to living beings, but they are not. They are simply self-organizing molecules.

“We have always approached the origin of life following the biblical text, as if there were a divine breath, a moment in which it is already irreversible. What our study suggests is that it should not have been like that, but that this is a chemical evolution of millions of years, absolutely random, like , and that increases in complexity over time. It can reach self-organized structures and, in some cases, self-assembled structures, like life,” explains García Ruiz. “These types of protoworlds must exist on billions of planets in the universe. And those protoworlds can reach something as complex as life or nothing. There is no intelligent design, there is no divine breath, but there is no fundamental reaction either,” emphasizes the geologist, from the .

Twenty-something Stanley Miller wrote his results in February 1953 and changed the way humanity saw itself. He showed that three gases, water and electrical discharges were enough to create amino acids in the laboratory, the components of proteins, which are the biological machines that form living matter. Juan Manuel García Ruiz’s team already de Miller in 2021, but changed the original glass container for a Teflon one. His conclusion was news: no brick of life emerged there. The silica – a mineral made up of silicon and oxygen – present in the glass was essential. Last year, a consortium headed by García Ruiz received from the European Union to study the origin of life.

The new experiment has generated amino acids and also the five nucleobases that are the fundamental ingredient of DNA, but the great novelty is the simultaneous appearance of these “protocells.” The geologist explains that they are a type of hollow vesicles, which compartmentalize space, enclosing the bricks of life and making it easier for them to react with each other, a key step in that immense primitive ocean. “These protocells must have also appeared in Miller’s experiment and in subsequent ones, but no one had looked for them until now,” says García Ruiz, who has led the research with his German colleague.

Their results imply that terrestrial life could have emerged hundreds of millions of years earlier than previously thought, during the Hadic, the geological period that began 4.6 billion years ago, with the formation of planet Earth, and ended about 4 billion years ago. of years. García Ruiz highlights that his “protocells” are formed, with the help of bubbling, of repeated units of hydrocyanic acid, a simple molecule with a hydrogen atom, another carbon atom, and another nitrogen atom. “There are several studies that suggest that everything can be created from these hydrocyanic acid polymers, everything you need to reach the basic building blocks of life,” says the geologist. Their study is published this Monday by the United States National Academy of Sciences.

The Mexican biologist remembers that, just 100 years ago, the Soviet scientist Aleksandr Oparin published his revolutionary book, in which he defended the hypothesis that the first organisms were the result of the chemical evolution of molecules in the primordial soup of the primitive Earth. In the middle of the Cold War, the young American Stanley Miller of the Soviet. “The merit of García Ruiz’s work is having followed the evolution of simple molecules until the formation of complex microscopic structures in the same system,” applauds Lazcano, founder of the Origin of Life Laboratory of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

The Mexican researcher, however, is cautious. “I would not call them protocells, because that suggests an evolutionary continuity that is far from being demonstrated, and that does not correspond to their chemical composition,” he points out. “They are right to write that they may have been microreactors that allowed other reactions, but we are still far from constructing a detailed and realistic sequence of the evolution that led from the inorganic components and molecules of the prebiotic Earth to the first organisms, among other reasons because we still do not agree on what could be a good definition of the first forms of life,” warns Lazcano.

García Ruiz himself emphasizes this uncertainty. “I would say that the conclusion of our work is that, today, the difference between the living and the non-living is less clear than ever, both morphologically and chemically,” says the geologist, who is also an emeritus researcher at the (CSIC) , in Granada, where his team carried out part of the experiments. García Ruiz warns that space missions will bring rocks from Mars in the coming years and amino acids, the nucleobases of DNA and even these “protocells” could be detected in them, but that will not mean that traces of extraterrestrial life have been discovered.

The philosopher of biology, expert in the origin of life and protocellular models, also applauds the “excellent work” of García Ruiz. “The relevance and specific interest of this research, beyond placing the first steps towards life in very remote times, lies in the fact that the synthesis of organic molecules à la Miller is here accompanied by the formation of compartments with a size, morphology and topology similar to those of a cell,” highlights Ruiz Mirazo, from the University of the Basque Country.

“It remains to be resolved – and I hope that this group will now address the challenge of demonstrating it – whether these types of closed and hollow supramolecular structures could be coupled to some prebiotic chemistry with which to co-evolve towards forms of organization, establishing mechanisms of exchange of matter and energy with their surroundings,” warns Ruiz Mirazo. “From my perspective, the encapsulation of biomolecular precursors, although necessary (as the authors of the article defend), is not in itself a sufficient condition for a compartment to be conceived as protocélula. However, this is how science advances, in all its fields: the more significant an achievement, the more open questions it raises around it. Continuing to investigate along this path will undoubtedly broaden horizons in the search for our deepest and most distant origins, as the biological entities that we are,” says this researcher.

Geologist Juan Manuel García Ruiz is preparing an expedition in 2026 to Kenya, a place that he considers relatively similar to that of the primitive Earth, with alkaline lakes and silica in abundance. In the meantime, his group will continue to repeat Miller’s experiment in new versions, for example by changing the temperature and adding ingredients such as sulfur, phosphorus and carbon monoxide. “We are going to extend the time and start cooking, and see what happens,” he announces.