February 23, 1996. Almost 29 years ago, I received the assignment to cover the delivery of the former deputy’s death certificate to his wife, Eunice Paiva, at a registry office in Sé, in the center of São Paulo.

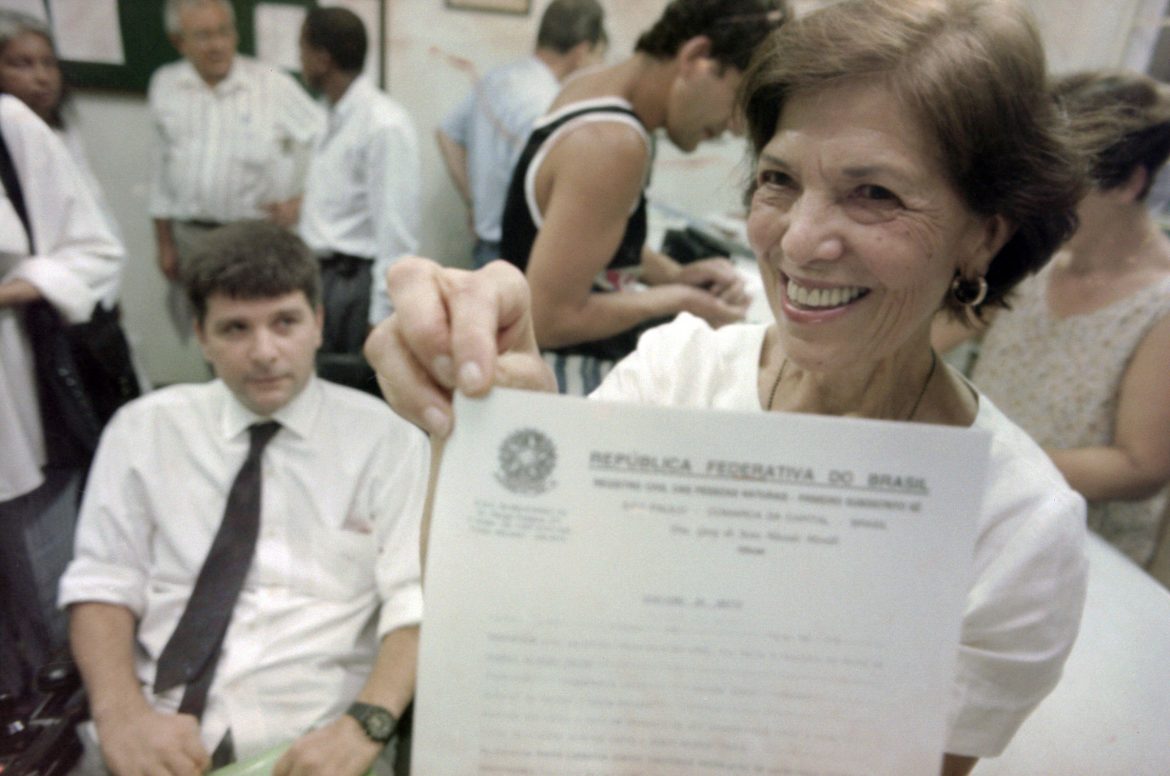

The cramped office, with shelves packed with beige files and lit by cold fluorescent light, was packed with reporters, a few cameramen and perhaps one or two more photographers. We felt the anxiety accompanied by her son up close. The scene was quick: Eunice received the death certificate from the clerk, put on her prescription glasses and read it in silence. Soon after, he showed the document, long awaited by the family, to the cameras. On the other side of the counter, the employees smiled when they saw the joy and relief of mother and son.

The scene and the photo I took of Eunice, Marcelo and the death certificate appear in the film “”, by Walter Salles. As João Bittar, photography editor at Sheet at the time, “we are not the ones who take the photograph. The photograph is given to us”.

On that February 23rd, I wasn’t sure of the weight of the historic moment I recorded. But it wasn’t just another agenda for me. I suffered personally, as the son of someone persecuted by the , the damage that years of lead caused in the lives of hundreds of families. My father, the publicist Carlos H. Knapp, was born in the same year as Rubens Paiva, in 1929, and had better luck: he managed to escape without being tortured, going into exile in . He only returned to Brazil in 1980, after the amnesty.

In the tunnel blitz scene, Walter Salles’ film shows a poster with photos of wanted “terrorists”. It reminded me of my father’s face on the same posters around the country when I was five years old. The repression left scars and harsh consequences to this day.