If you are from the north, you may have already seen some reference to these symbols, which are part of Poveira culture. More than decorative, they were a way of organizing everyday life — especially for the illiterate.

Póvoa de Varzim, in the Porto district, has as its main tourist attractions — besides the beach, of course — the Mother Churchwhich dates from the eighteenth century, ea Lapa Church.

In these places, instead of proceeding as in common churches, where we look up to appreciate the altarpieces or domes, it will be more interesting if look at the floor.

There, as well as on the walls and doors, you will find the poor acronyms, a proto-writing system whose similarity with viking runes raised the intriguing hypothesis of a Scandinavian origin. And the researchers weren’t mistaken, says .

In fact, Póvoa de Varzim was once an ancient Roman settlement, Villa Euracini, which used to be the site of a hillfort, Civitate do Terroso. By the 18th century, the city had grown so much that it became the country’s main fishing port.

But it was long before, from the seculo IXwhen the region was still part of the first County of Portugal, founded by Vimara Peres, who Viking fishermen from Brittany began to settle in the city.

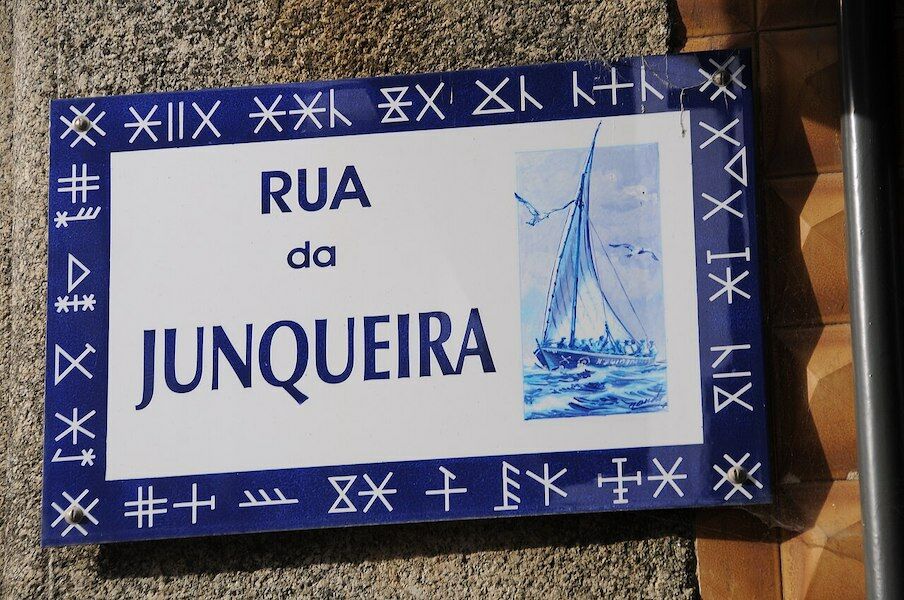

The poveira speedboat, a traditional type of vessel in the area, is one of the legacies of this occupation. But another interesting memory from those times are the poor acronymsalso known as “signs of Póvoa”.

PeterPVZ / Wikimedia Commons

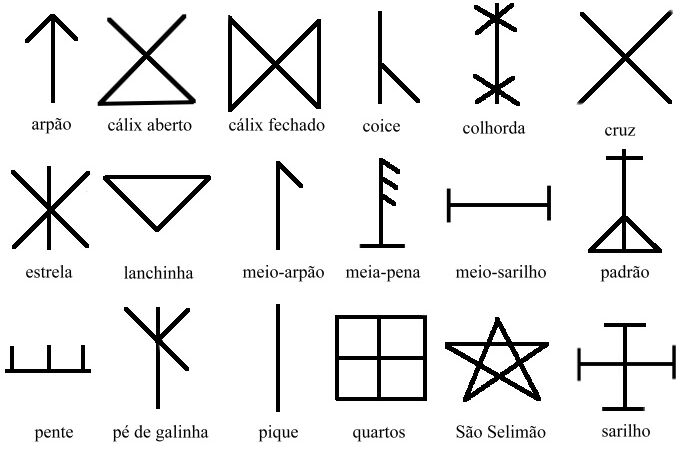

Some common Portuguese signs

The LBV also makes a list of other northern points of the country where it is possible to find these marks: the temples of Senhora da Abadia and São Bento da Porta Aberta (in Terras de Bouro), São Torcato (Guimarães), Senhora da Guia (Vila do Conde), Nossa Senhora da Bonança (Esposende) and the Chapel of Santa Cruz (Balazar),e. even in the Guarda (in Galicia, Spain, not the Portuguese Guarda).

But, after all, what are these inscriptions?

Most of these marks are found in religious places, as local fishermen used to carry them with them in veneration of local saints.

And its origin is easy to understand: the majority of Portuguese people at that time were illiterateand the Vikings created symbols that were easy for the entire population to recognize. The symbols were therefore painted on boats, but also on barracks, graves and even on accounting booksto make life easier for sinners.

There were thousands of symbols, and could represent, for example, a family. They are not, however, associated with phonetics — they were merely a design, recognized by the community as significant in x or y.

In the case of familiar symbols, or anagrams, signals were transmitted from generation to generationand, in several cases, dashes, called spadesin front of the symbol, which represented a new generation, as illustrated in the image below.

PeterPVZ / Wikimedia Commons

Example of spades added to a symbol of a family

Most of the signals they were ideographically inspired by everyday objects. By way of example, the cruise of the Póvoa de Varzim cemetery inspired the standardjust like Wing-Up (an expression sung by people when they pull boats from the water to the sand) inspired the kick (an oblique line that represents a boat in this situation).

At the moment, there are only a few hundred signs leftsignaled by Antonio de Santos Graçathat these symbols and Poveira culture, in his book Epic of the Humblepublished in 1952.

Today, the inscriptions that are still visible in the churches mark these times, but also some tributes on toponymy plaques in the city, or even on the sidewalk in Poveira.