On Thursday we received the news from , the Colombian scientist who played a central role in the scientific revolution of malaria vaccines that began in the 80s of the last century.

I met him at a parasitology conference in Mexico in the late 1980s. He entered an auditorium full of circumspect scientists surrounded by a swarm of television cameras and photographers, like a true rock star, something unusual in the world of science. . His keynote talk was packed with slides, so many that there was barely time to read or interpret the graphs. It was a real , but enough to convince us – at least some of us – that, together with the two articles that he had published shortly before in the magazine Naturewhat he proposed was potentially disruptive and deserved to be analyzed with attention and rigor.

Malaria is a parasitic disease that, according to some, is the one that has claimed the most human lives throughout history. With a complex biological cycle and sophisticated immune evasion mechanisms, it is transmitted by the bite of female anopheline mosquitoes and represents an enormous challenge for science and global public health. More than 600,000 people die every year, most of them African children; More than 200 million cases occur, and the disease is endemic in countries that are home to more than 3 billion people. Malaria is a paradigm of diseases that are the cause and consequence of poverty, and an example of market failure that discourages industry from investing in solutions to such complex scientific challenges.

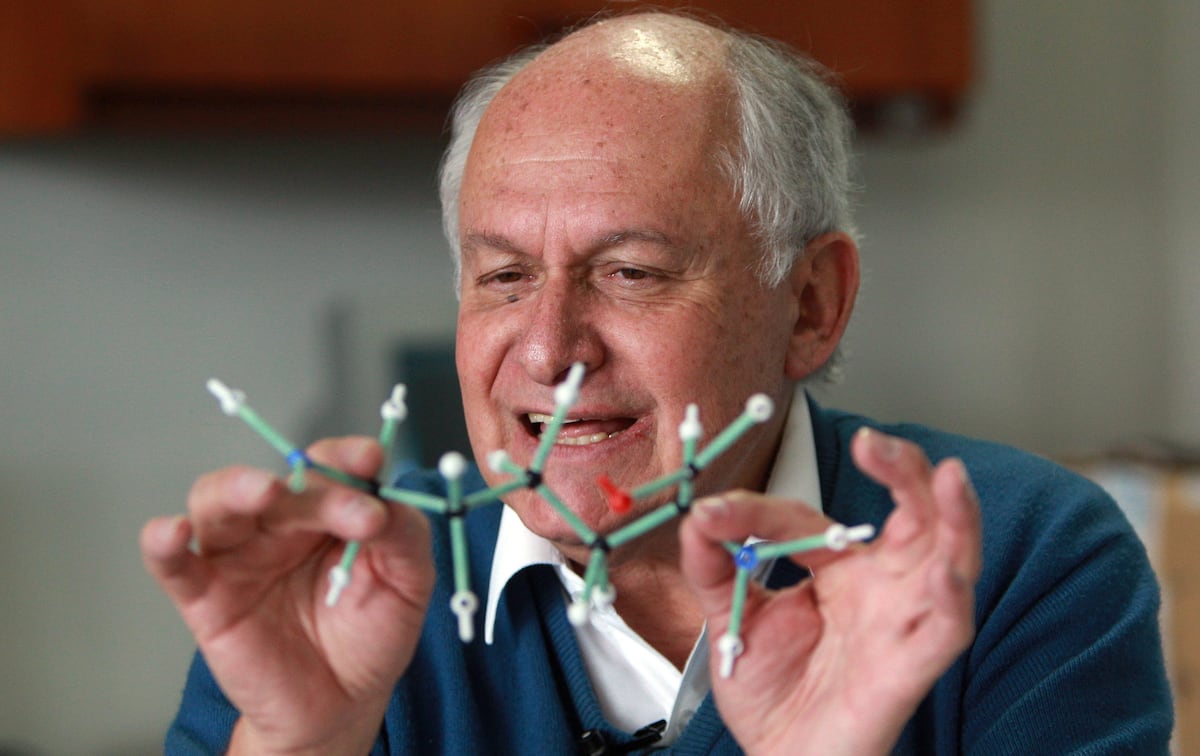

The cloning of the parasite’s first gene by North American scientists in the late 1970s inaugurated a time of hope in the possibility of developing, for the first time in history, a vaccine against this parasite. However, lack of funding and limited efforts limited these initiatives, which remained mainly in the hands of the US military’s research institutes. It was in this context when, in a surprising way, Manuel Elkin Patarroyo emerged, a doctor unknown in international scientific circles, from a country with little tradition in this field, who announced that he had developed an effective vaccine against the Plasmodium falciparum. Using a novel platform—synthetic peptides—he published data in journals of maximum international impact that demonstrated that his vaccine could, like human volunteers, against this deadly parasite. It was a real revolution.

In a matter of months and with extraordinary speed, it launched clinical field trials in Colombia, as well as in Venezuela, Ecuador and Brazil. The World Health Organization, interested but also skeptical about the high levels of vaccination and concerned about the announcements of imminent mass vaccination campaigns, sent an international committee of experts to Bogotá to evaluate the available data. The conclusions were clear: the studies had methodological flaws that prevented firm conclusions about the effectiveness of the product and recommended independent studies, especially in Africa, the epicenter of malaria.

The studies carried out in the following years showed: from moderate effectiveness in children aged 1 to 4 years in Tanzania – although none in newborns – to very low or non-existent effectiveness in Gambia and Thailand. Personally, I have always believed that part of these contradictory results was due to the platform used. Synthetic peptides and their polymerization made product standardization difficult, causing variations from batch to batch. The product tested in different countries and studies was not always exactly the same. However, I have no doubt that his vaccine provided the first evidence that it was possible to induce protective immunity against malaria. The studies conducted by scientists in Africa were the first large trials of a malaria vaccine and helped the international community define standards to rigorously evaluate vaccines and generate the information necessary for their registration. That methodology is still used today.

It should be noted that Patarroyo’s vaccine candidate included fragments of the circumsporozoite protein, cloned by Ruth Nussenzweig, which is also part of the two vaccines that are currently being deployed in Africa.

Manuel Elkin Patarroyo was a force of nature: visionary and disruptive. He had an overflowing imagination, tireless energy and an extraordinary capacity for work. Friendly and captivating, his volcanic and transgressive personality left no one indifferent. It generated admiration and rejection in equal parts, polarizing the scientific community. In Spain, he had great recognition and institutional, political, emotional and scientific support, in addition to receiving well-deserved awards and distinctions. His figure embodied the image of a humble and quixotic researcher, coming from, who fought for a just and universal cause, ignored or even despised by the great world scientific powers, especially the Anglo-Saxon world.

The impact of his work is immense. He trained generations of Colombian scientists, many of whom work in some of the best scientific institutions in the world. He built research institutes of excellence in Colombia. Although its vaccine was never used due to reasons of effectiveness and quality, the malaria vaccines that are currently being applied in Africa, saving thousands of children’s lives each year, have benefited from the knowledge generated with SPf66, the name of his vaccine, and of the paths he opened.

His legacy is enormous and his personality is unrepeatable.

Pedro Alonso He was director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme. He is a professor of Global Health at the University of Barcelona/Hospital Clínic.