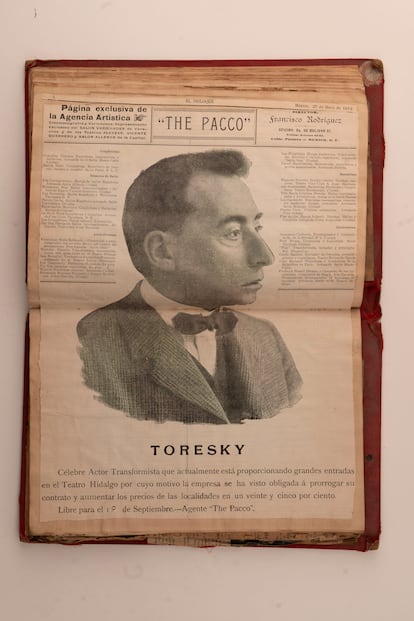

Almost a century later, the cause of death of Josep Torres Vilata (Barcelona, 1869-1937) is unknown. Although the autopsy of the first radio star in Spain determined a stroke, whether the stroke occurred after being arrested for uttering a political joke on the air in full , is a mystery. As the reason for his hasty escape from Barcelona towards America, where he became a star of the show. Or the ingenuity from which he extracted ideas that, even today, are played daily on the radio. , a documentary released on the free platform CaixaForum+ and directed by Cosima Dannoritzer, now discovers for the general public an almost unknown character surrounded by mystery.

Life of a hustler. “He died of fear,” says one of Toresky’s relatives in the documentary, which gives an account of a life that led the actor and drag queen to first survive poorly and then succeed as an artist halfway around the world. And to end his days in a Barcelona enveloped in the disorder of the war, and which said goodbye to him in a mass funeral, becoming the most famous announcer on the newly born radio station. An idol among the popular classes that earned him, in 1934, the Grand Cross of Charity, from the hands of , for converting the new means of mass communication into a vehicle for helping the disadvantaged, with the help of a fictional character in the waves.

The only son of a Catalan industrialist who made a fortune with the patent for a lighter and who ended up bankrupt after the emergence of the electric light bulb, Josep Torres put his foot down when debts suffocated the buoyant family business. In his escape to Cuba, he left behind the florist from La Rambla whom he married and their newborn son, whom he did not see again until his return to Spain, a decade later. He left on the ship Reina María Cristina on September 20, 1893, on a long, arduous trip without a preconceived plan.

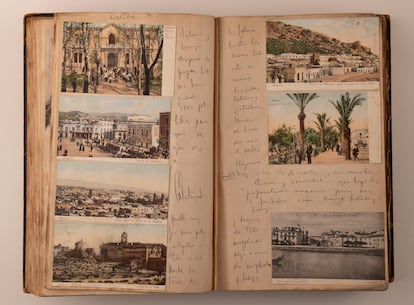

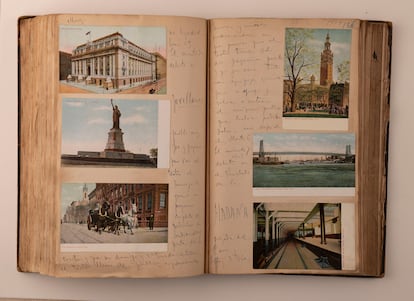

It is in Cuba where, at the age of 27, he began to work in small companies as a ventriloquist, actor, rhapsode and director and singer of zarzuela, until he headed to the United States in 1895, willing to learn English and try a luck that New York offered him. denied in a first round. “Today’s food has been water from the public fountain. I’m tired of asking for work to no avail. “I sit on a bench in Union Square, ready to spend the night,” he wrote one day when his jobs as a dishwasher or hotel doorman allowed him to complete his diary.

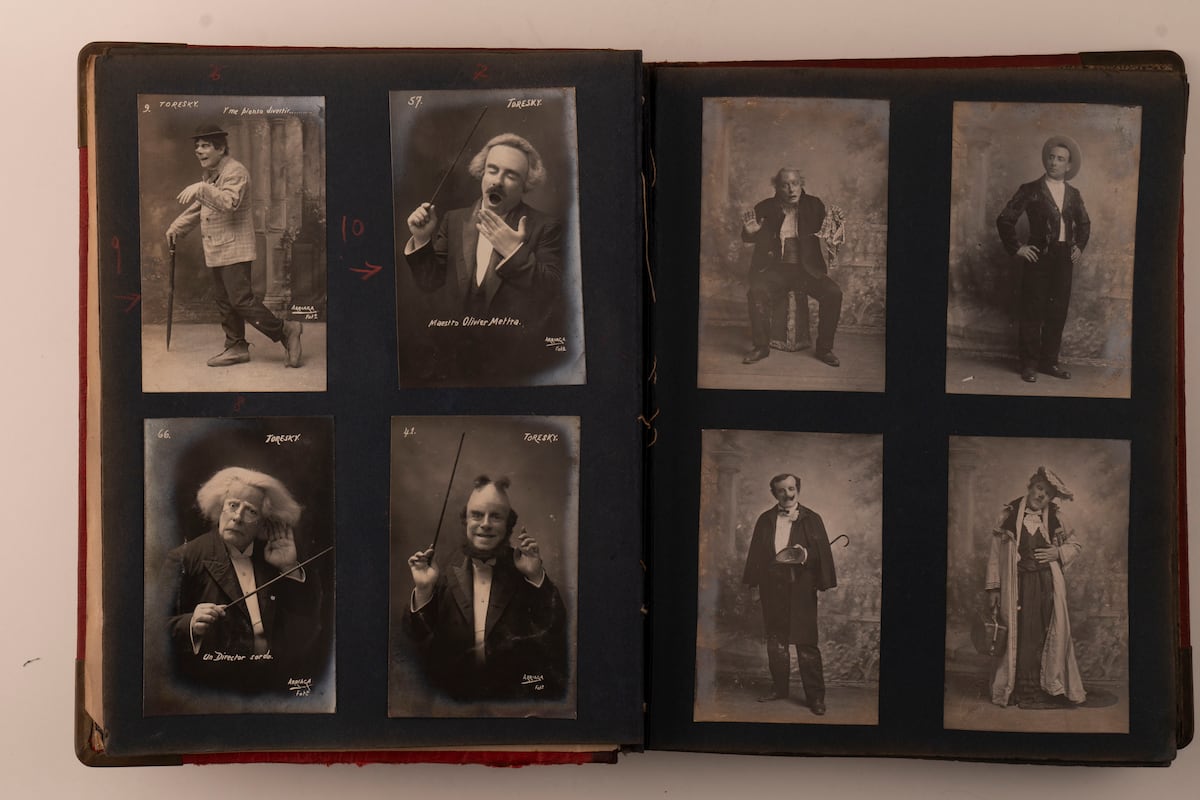

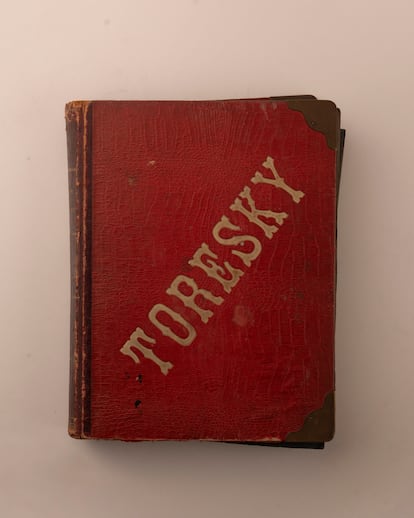

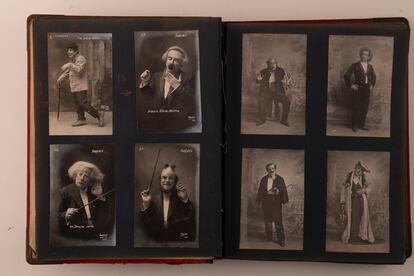

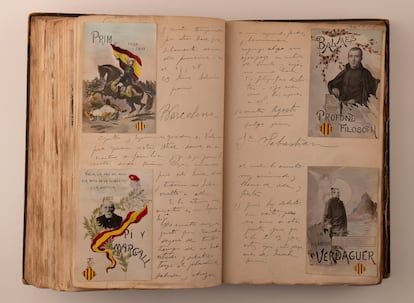

Returning to Latin America, his stage name began to be common in theaters in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Colombia, Argentina and Havana. Coincidentally, there, in 1897, he met a world-famous Italian. With the help of one of his collaborators, and taking advantage of a mistake on the part of the artist, Toresky discovered how to manage, with a few pieces of costume, to cross-dress before the public as a cook, a dolled-up lady, Victor Hugo or Richard Wagner.

return home. Success kept him away from home until 1903. “Finally, after 10 years of absence, he arrived in Barcelona. “I don’t want to go home without telling them first,” he confesses, fearful of his wife’s reception after his disbandment. A month later, Toresky embarked on a tour of France, Portugal and Spain and, in 1907, headed again to America, with performances at the Gran Teatro Nacional of Cuba, shows in English in the United States and a second foray into New York, this time with passage in first class and five collaborators who accompanied him in a debut at the American Theater that led, in 1913, to Columbia Records to hire him to record six albums.

In 1916 Toresky traveled to the Philippines and Hong Kong, where his popularity was such that he noted: “The public forces have had to make different efforts to prevent citizens without tickets from attacking the theater.” His success is only the preview of his greatest triumph: a meteoric stardom on the radio.

The radio. Toresky. The prodigy of imagination portrays a hustler who, with the gift of opportunity from Woody Allen’s Zelig, was in Madrid on the day of the anarchist attack against Alfonso Until the outbreak of the First World War: “This war will ruin a very brilliant career for me,” he laments.

But the greatest demonstration of his gift of opportunity occurred on September 24, 1924 in Barcelona, when the then first radio station licensed to broadcast in Spain, hired him as an announcer and commissioned him to devise a formula so that advertising by words It would be less repetitive. This is how Míliu was born in 1927, a child character to whom the announcer gave voice in humorous dialogues between the two during advertisements.

The popularity of the character was also Toresky’s main attraction when he launched the first radio program in Spain dedicated to charity, with which he raised two million pesetas of the time, thousands of toys and countless donations for hospitals and orphanages, in a solidarity work that continues today programs such as No child without a toywhich every year from Ràdio Barcelona, with the host Rosa Badia, collects toys on Three Kings’ Day.

Toresky was also a pioneer when it came to bringing the sense of theater spectacle to the airwaves. “The first announcers came from vaudeville. I, who am from that union, claim the radio as a theater from which to address the public,” the presenter and comedian Andreu Buenafuente says in the documentary. Toresky’s legacy as a radio ventriloquist has reached our time also in the dialogues that the comedian Juan Carlos Ortega, narrator of the documentary, displays today on the air.

Toresky thus became the first announcer to introduce humor on the radio in Spain and to circumvent the censorship of the .

It was, however, a joke that ended his fortune. During a broadcast, Míliu asked him: “Why are there bars in prisons?”, to which Toresky replied: “So that thieves don’t get in.” “The CNT, which controlled the prisons, must not have liked the joke, and they arrested him,” summarizes Armand Balsebre, professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. “He was accusing the Government of having become criminal,” says Marià Veloy, whose novel The world begins (Bromera, 2022) traces Toresky’s life.

The end of his days, at the age of 67, came in this way in 1937 in the midst of violent clashes in Barcelona, between Stalinists, Trotskyists and anarchists. A statue of Míliu in the gardens of the Sagrada Familia, the main studio of Ràdio Barcelona, and now a documentary remember the legacy of the first radio media phenomenon in Spain.