Hilda’s arrival was heralded as a historic milestone for reducing the industry’s carbon footprint.

Hilda is being heralded as a major step forward towards a more environmentally friendly dairy and livestock industry. But is technology enough to contain the sector’s impact on the climate?

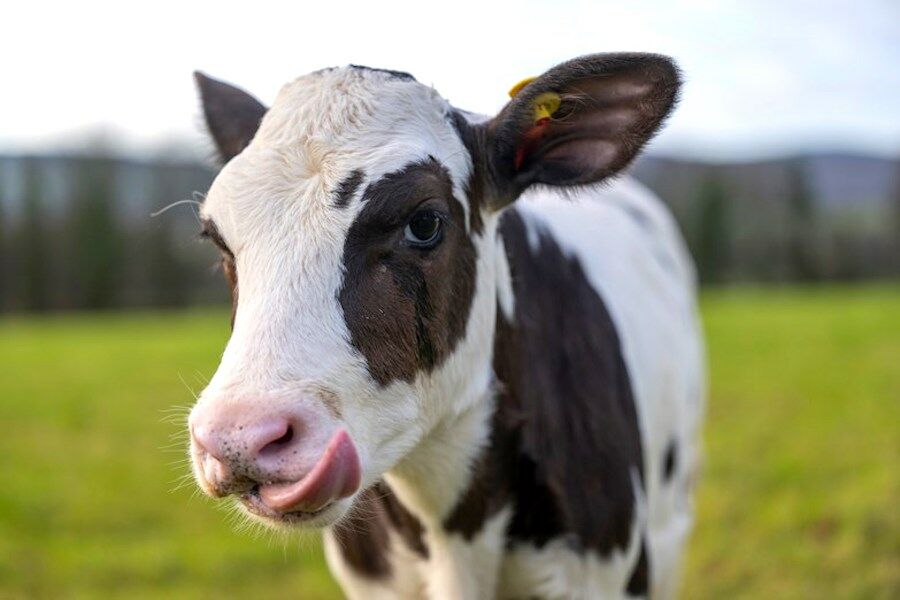

The birth of a dairy cow in Scotland is being celebrated as a revolutionary moment in efforts to reduce agricultural emissions.

Bred to emit less gases, Hilda is the first calf from the Langhill cow herd in the south of the country to be born through fertilization in vitro.

Cattle burps and manure produce methane, a greenhouse gas that heats the planet and is up to 80 times more powerful than CO2 over a period of 20 years. Livestock farming generates around 30% of global methane emissions, with two thirds of this volume coming from cattle used to produce meat or milk.

The arrival of the Scottish calf has been hailed by vets and scientists as an important moment in reducing the sector’s carbon footprint.

Accelerate methane slowdown

Hilda is the result of the combination of three technologies, explains Mike Coffey, professor at Scotland’s Rural College, a university focused on sustainability and a partner in the project.

The ability to predict a cow’s methane production based on its DNA, the extraction of eggs from younger animals and their fertilization with selected semen are the technologies in question. The three “allow the selection of females to be accelerated to reduce methane production — one calf at a time“, explains Coffey. Repeating this procedure for a few years would result in a herd with low methane emissions.

Rob Simmons, from Paragon Veterinary Group, another partner in the project, told PA Media that the “genetic improvement in methane efficiency” will be “key to continuing to provide nutritious food to the population, while controlling the impact of emissions of methane in the environment in the future”.

Reductions of up to 30% by 2050 in the crosshairs

The Langhill herd is the focus of oldest livestock genetics project in the world and selects cows based on factors such as health, fertility, productivity and feed consumption.

Traditional selection based on these characteristics has so far helped to reduce methane emissions by around 1% per year, according to Coffey, who guarantees that this new technique should increase these reductions in 50% each yearwhich would be equivalent to a 30% global reduction in emissions over the next 20 years.

A Canadian study published last year also suggested that farmers who select and breed cows to improve methane emissions could gain reductions of up to 30% by 2050.

“It wouldn’t be profitable”: the electric car analogy

In total, there are 1.5 billion cattle in the world, of which around 270 million are dairy cows. In 2022, the global dairy sector was worth almost $900 billion (around €823 billion).

The process of producing a cow like Hilda currently costs about twice as much as the economic value of the animalexplains Coffey. “It would not be profitable [para os agricultores] as it currently stands. But the point of this project was to demonstrate that it can work.”

Coffey says that the next step will be to find ways to finance the expansion of the project. “[Queremos saber] what levers does the government have to make this economically viable for farmers, just like they did with electric cars.”

Coffey believes the transition to electric cars is a good analogy for the speed of change in reducing methane from cows.

“There will be a time when they stop making gasoline cars, but the existing gasoline cars will continue to circulate, and this is similar to what happens with herds of cows.”

However, Coffey emphasizes that this project is part of a much broader scientific effort. In addition to genetic selection, other projects analyze the impact of feed additives, such as seaweedor the capture of methane produced by manure, transforming it into biogas that can fuel vehicles or heat homes.

The Langhill herd has also been used in studies exploring how dietary changes and fertilizer use affect greenhouse gas emissions from dairy farming.

“Most other countries in the world are doing the same. It’s like an international race to reduce methane emissions from ruminants as quickly as possible,” explains Coffey.

There are more than a million fertilization attempts in vitro per year, half of which take place in North America.

Is selective breeding enough?

Methane emissions are increasing faster, in relative terms, than any other greenhouse gas, according to a Stanford University study.

Os meat and dairy sectors contribute 12 to 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions and are responsible for 60% of emissions from food systems, according to an article published in the journal Nature Food. This is largely due to carbon dioxide released by the deforestation of forests for pasture and food production, as well as methane generated by livestock farming.

According to another study published in Nature Climate Change, reducing meat and dairy consumption could reduce global emissions from diets in 17%.

Despite the growing popularity of plant-based alternatives – such as almond and oat milk – in some parts of the world, the Milk and dairy products are consumed by around 6 billion people worldwideand demand is expected to increase steadily over the next decade, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), which also predicts an increase of up to 14% in global meat consumption by 2030.