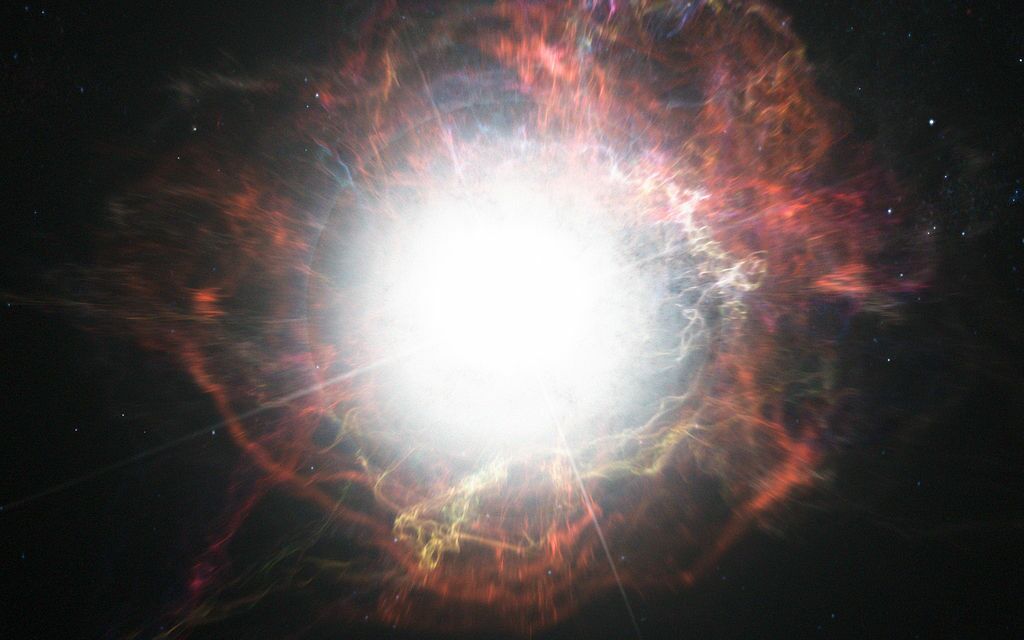

Artistic impression of dust formation around a supernova explosion.

The traces may be linked a rare Kilonova that had occurred about 10 million years ago. Scientists want to take advantage of the Artemis mission to also analyze moon samples.

A new research presented by the astronomer Brian Fields in the global summit of physics at the American Society of Physics of 2025 points to the discovery of traces of radioactive plutonio in the depths of the seawhich may be linked to a rare cosmic explosion known as Kilonova.

This extraordinary discovery suggests that the remains of some of the most violent events in the universe have reached the oceans of the earth and can also be preserved on the moon.

The study is based on decades of research on cosmic debris. Since the 1990s, Fields has theorized that the remains of supernoves have accumulated on Earth, a hypothesis confirmed in 2004 when scientists have detected radioactive iron isotopes in ocean samples. These traces were identified as remains of supernovae that occurred 3 million and 8 million years ago.

However, in 2021, researchers found an even rarer element mixed with these samples: a radioactive plutonium isotope. Unlike iron, which is produced by the supernovae, it is thought that this plutonium originates in the Kilonovas-cataclysmic events that occur when Two stars of neutrons collide. These explosions are responsible for the formation of some of the rarest elements on earth, such as gold and platinum, explains the.

Fields and his team now believe that a Kilonova event took place at least 10 million years ago, prior to the two identified supernovae. The materials from these explosions mingled, forming a “radioactive cocktailWhich eventually settled in the deep marine deposits of the earth.

To reinforce their findings, researchers are turning to another cosmic file: the moon. Unlike the earth, where geological and atmospheric processes redistribute the materials, the surface of the moon acts as a immaculate of extraterrestrial debris.

Currently, lunar soil samples remain scarce, but Fields is optimistic about the fact that future missions will provide vast study material. “At this moment, our lunar soil is so precious because it is all we have,” he said. “The hope is that, eventually, routine trips to the moon facilitate sample collection.”

As Artemis missions advance, scientists are preparing research proposals to ensure that the analysis of cosmic debris is included in the next studies. “The samples are returning anyway,” said Fields. “We just want to take the opportunity.”