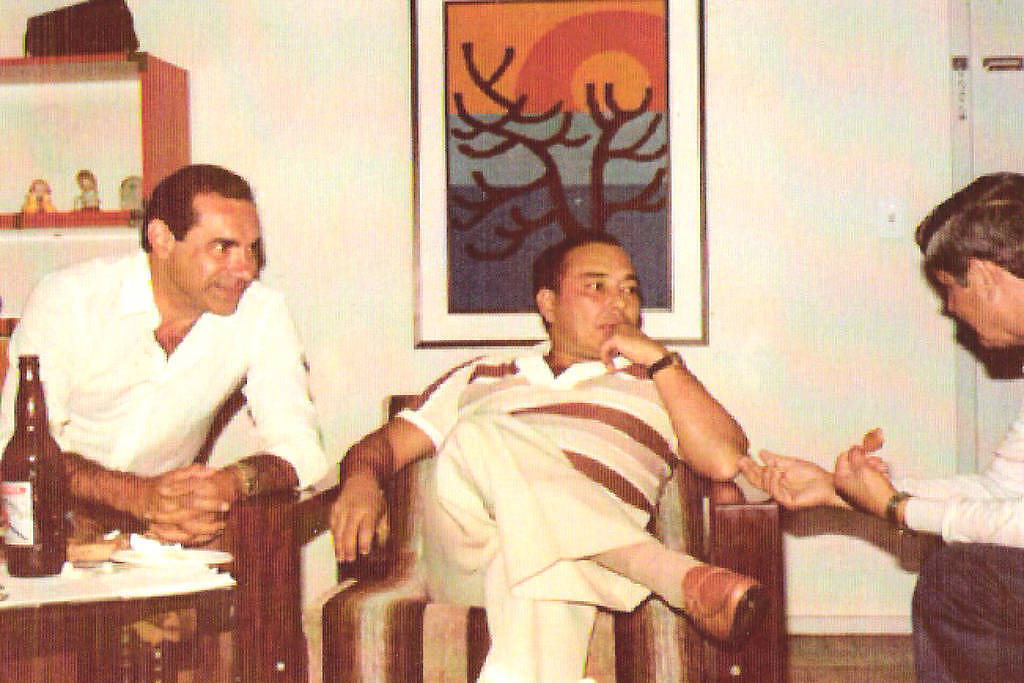

In the cover photo of the book “Torturers”, by historians Mariana Joffia and Maud Chirio, the same that illustrates this report, the army military (both then Majores) and André Leite Pereira Filho (captain) chat, in civil and relaxed face, in front of a bottle of beer.

That early 1970s, in the wake, was one of the most violent times of the dictatorship. The accompanying caption says that they are in the DOI leadership room (Detachment of Information Operations) of the 2nd Army in Sao Paulo, infamous Military Regime Torture Center – Comtended by Ustra from September 1970 to January 1974.

Launched by the publisher Alameda, “torturers” is the result of 14 years of research by, professor of contemporary history at Gustave Eiffel University (France), and professor of history of the Americas at UDESC (Santa Catarina State University).

Unlike the cover photo, the book does not bring individual profiles of the tormentors referred to in the title.

Although Ustra and Malhães appear a lot over the 300 pages – second, a rare, is the subject of an entire chapter, based mainly on a long statement he gave to the RJ State Truth Commission – the authors chose to make the so -called prosopography: a collective biography, the profile of a social group.

Chirio, Frenchman who speaks Portuguese and has been researching Brazil for years, and Joffily say they were moved by the scarcity of academic research on the subject in the country. The reasons for such a scenario, they evaluate, range from the difficulty of access to sources to the “feeling that there is a moral problem in the fact that they adopt these men, their trajectories and acts as the object of history.”

“Although explaining does not imply excusing,” they write, “specialist researchers of characters strongly condemned by collective memory and public space are often considered suspected of contributing to rehabilitating them, or at least exempt them from their responsibilities.”

On the other hand, the authors claim that in historiographies from other countries has multiplied over the past 15 years the study of the so -called “perpetrators”.

The option for collective portrait, said Chirio, sought to minimize the risk, “when focusing on individual personalities, of involuntarily creating a certain fascination in readers.”

It recognizes the importance of so-called microhistory, that is, of writing general history from an individual experience. “But this is possible when you already have an idea of the set. You can’t do the microhistory of a time or a historical object you know so few things. And we had no information about the repression staff.”

What interested them in the photo of the cover, notes Joffily, was precisely to show those three men – too late accused of barbaric crimes – in a laid -back situation, taking a beer and quietly prostage “inside a room that was one of the country’s major torture centers,” in contrast to the classic idea of dictatorship. “[É um modo de mostrar]Look, this was an everyday task. They are public servants in the performance of their work. “

The convergence of interest took place in the wake of doctorates on dictatorship themes that would later be published in books: in the case of Chirio, “politics in barracks: revolts and protests of officers in the Brazilian” (Zahar); In Jofffe’s, “at the center of the gear: the interrogations in Operation Bandeirante and the São Paulo Doi – 1969-1975” (Edusp).

In 2011, at a USP History Symposium, they agreed that in their research there was a gap just about the “leaders.” It was the beginning of a joint work that resulted in texts published in academic magazines and book chapters in Brazil and abroad. The work now released brings together them all and adds them two unpublished texts.

In the eight chapters of “torturers,” the authors seek to answer the following questions: why did they get involved in repression? Who were it?; How were they trained?; How did they circulate?; What careers have developed?; How were they exposed to civil society? How do you see yourself? (dedicated to Malhães); And what were the motivations of the torturers?

The starting point of the survey was the torturers lists released by political prisoners from 1975, starting with the detainees of the Federal Military Justice Prison of Barro Branco, in São Paulo – “Bagillão”. Later this and others would be published in the alternative newspaper in time. The relationship would grow thanks to the Brazil Project: never again, from 1985, from processes of the military justice itself.

The crossing of the names of the lists with the functional records of the main accused of torture allowed them to reach 170 individuals, three army military rooms and the rest of civilians or other military personnel who collaborated with them.

The army is the protagonist armed force, either because it was indeed the one that led the coup and the dictatorship, but because it also has public documents about its staff-and only in this respect, as it is a black box in most information about the repressive period.

The authors used the dossiers of schools of officers, almanacs, internal bulletins (promotions, awards) and especially what they call “our grail”: the leaves of alteration, which condens the trajectory of the military according to the units in which they served. They got several on their own and had access to those obtained by the National Truth Commission.

In chapter 5 (what careers did they develop?), They selected 20 officers who participated in the creation of the Doi-Codi of São Paulo and Rio, a kind of repression of repression. In the list, in addition to Ustra, there are other notorious perpetrators, such as Ailton Guimarães Jorge, the –Cuscated by teaching torture in the dictatorship and then became a bicheiro – and one of the.

They were mostly young officials from ECEME (Army Command and General Staff), at a time when “222 hours of internal security classes, 129 insurrectional war and 21 classical territorial defense” were taught at the institution.

The main conclusion of the research, says Chirio, is that “the central pillar of dictatorship repression was the constitution of a group of experts trained in intelligence techniques and counterrevolutionary theory, mostly from the army.”

“This group will be the center of the success of repression, which works very well in Brazil, and then the Irradiation Center on the continent, from the second half of 1970, which makes Brazil the model, the mainland teacher in terms of contraindinsurial techniques.”