Amanda Cox // Your

Colin Wyatt’s theft of butterflies is a bizarre and fascinating story and has begun an agitation that still has an impact on science today.

According to, retreating until 1942, when a British called Colin Wyatt He traveled to Australia to work in the Air Force, taking his wife, Mary.

Wyatt era um Olympic ski jumping championone Military camouflarone authorone yodles singerone painterone Enthusiast naturalist and one butterfly collector. One Renaissance manas it were. In the reports of the newspapers of the time, it is also often described as “charismatic” and “beautiful”.

Wyatt used his charm and notoriety to access the most extensive collections of Australia Museum Butterflies.

For an obsessive collector like Wyatt, a rare butterfly is as valuable as a rare diamond. Therefore, he led a robbery – with a chivalrous touch.

Under the pretext of updating a book on Australian butterflies, Wyatt was invited to enter the secret rooms of the museums, where are the most coveted specimens of insect collections.

Then simply leave the museums with Small cans full of butterflies in the pockets and under the hat. On Wyatt’s trip to Adelaide, it is said to have come to lock yourself at the museum at night to do the work covered with darkness.

In several visits for 1946, Wyatt smuggled about three thousand specimens of butterflies from Australian museum collections.

Wyatt sent the stolen collection to his home in England and soon returned by plane. This time, he returned without Mary. Had separated during the stay in Australia. In your home empty Wyatt dedicated himself to etiquetar all specimens stolen with collectors and fictitious placessometimes with your own name.

Almost immediately, he spread to the people of the Australian museums the news that there were holes in their butterfly collections. You More rare and harder to find specimens were simply missing.

Scotland Yard detectives were called to investigate the case of missing butterflies. After a process that lasted a year, They eventually accused Wyatt, recovered 1600 of invaluable specimens and sent us back to Australia.

Wyatt declared himself guilty of the theftalthough he said he was not in his perfect judgment after his recent divorce. The judge seemed to sympathize with this excuse.

According to Time magazine, “the judge let him go easily, understood” the distraction of his mind “that he had taken Wyatt to a passion crime.”

Australian curators were tasked with meticulously sorting to specimens returned to their original files.

A curious yellow label remains in each specimen to this day to say: “Passed CW Wyatt’s theft collection1946-1947 ″, as a reminder that there is a small element of doubt to curl around each specimen played by Colin Wyatt.

72 years later

Advancing 72 yearslet’s go to the Michael BrabyLepidopterista, at Australian National University.

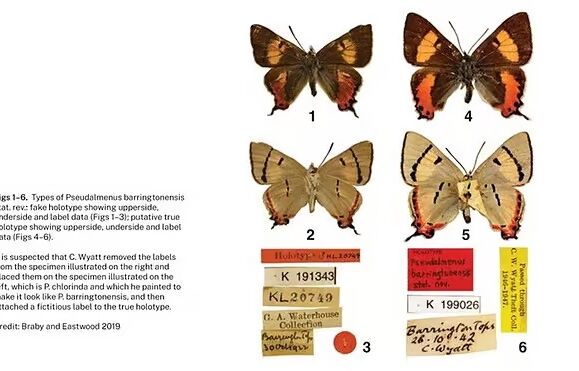

Braby has no idea that he is about to discover the Greater taxonomic fraud in Australia. Noticed something strange in this particular butterfly, a Flame Hairstreak (Pseudalmenus barringtonensis).

Lepidopterist approaches the zoom To see more closely and in the “flame” characteristic of the butterfly, the scarlet spot in the dark brown rear wing, seems to have been patched with red paint.

The associate teacher, who belongs to the Anu Research School of Biology and Csiro, passed about 30 years to investigate butterflies and mothsSo when the alarm begins to sound about this specimen of suspicious look, it follows the subject, contacting a colleague.

“I thought it could have been an accident,” says Braby, thinking that someone could have tried to blame for a damaged wing.

But soon after, the colleague Rod Eastwood It makes a suggestion: “It has to be related to the 1947“ Colin Wyattfly Heist ”.

Although there was no of those yellow labels in the Flame Hairstreak specimen, in Baby’s photograph, he was starting to agree with his colleague who It could be mixed in the Wyatt case.

Wyatt, who had exposed his art in Australia, had the skills of painteras well as the means and the reason to falsify A specimen of the Australian museum collection.

In 1946, this was the only known copy of a Flame Hairstreak In the world. There is no doubt that it would have been in Wyatt’s wish list.

Braby argued that Wyatt could have stolen the rare specimen and then placed the rather realistic forgery that he created in his place, so that no one suspected of him.

But in the meticulous world of taxonomy and collecting museums, cHamar attention to a fake is an extraordinary attitude. Brain needed proof.

In addition, to finish the scientific article in which they were working – the revision of the taxonomic status of this species of butterfly – Brain and Eastwood needed to examine the true original specimen, called holoty.

Thus was born a parallel mission to unravel this mystery.

Brady moved to Sydney to visit the museum and examine the collection with her own eyes.

Michael Braby and Rod Eastwood.

He came across a particular specimen that stood out as a great candidate for the plain bird’s bird’s holotype. It was much better than the supposed holotype specimen I had seen on the computer screen.

“There was a Wyatt Theft collection label, a similar date in the 1940s, but it had a different location label,” explains Braby.

Braby called the conservative of the Australian museum apart and explained what he had found.

Stressed that, in addition to the red -painted wing, There were other dubious differences that pointed to the falsification of the specimen. The black wing lanes of the (alleged) forgery were not in the correct guidance for a Flame Hairstreakand the orange track was intertwined with non -apparent black candles in the collector’s original drawings.

In Wyatt’s memories, which describe their collector’s adventures of, you can know exactly where you traveled and when, setting up a chronology lived from your collection. But Braby found that the labels of these two specimens did not correspond to the collector’s alleged chronologies – that is, until he exchanged the labels.

Wyatt never went to the remote town of Barrington Tops, where the Flame Hairstreakbut went to Blue Mountains, where he reported his excitement by collecting multiple examples of another similar species, the Silky Hiarstreak (Pseudalmenus chlorinda) – A species that has black veins in the orange wing section.

“When I told the curator, he was stunned,” says Braby. “It was just shaking my head.”

Brain and Eastwood published an article in which they exposed their case, concluding that Wyatt had stolen the original holotype of Flame Hairstreak for its private collection, then replaced it with a specimen of Silky Hairstreak That he himself had collected and created and painted him carefully like a forgery, exchanging the two genuine labels.

Never before had been discovered a forgery in an Australian national collection of insects.

In his 2019 article, Braby and Eastwood wrote that “Wyatt’s fraudulent and apparently unprecedented act Creating the fake holotype has gone unnoticed for 72 years and must certainly be classified as the largest taxonomic fraud in Australia. ”

After the publication of this article, another specimen of counterfeit butterfly was found by a scientist named John Tennentfrom the London Natural History Museum in 2024. Tennente also attributed this to the actions of Wyatt.

The butterfly effect

Like the judge at Wyatt’s trial in 1947, some may ask if stealing a lot of dead butterflies is so important, but These things are really important to science.

Wyatt stole from public registrationwithout worrying about how the removal of unique original specimens could derive the appointment and classification of species in the future.

“What he did is beyond words,” says Braby. “Museological institutions are the basis of our taxonomy and nomenclature and therefore effectively support the Our knowledge of biodiversity“.

A Taxonomy is the universal language which is the basis of all global biological systems. There is a code of conduct that must be followed when describing a new species for science, and each step is crucial to ensuring that registration is accurate.

The code stipulates that when an article is published with the name of a new species, it is It is necessary to present a holotype, as physical proof of the species.

“The idea underlying the existence of a holotype specimen is that there is no doubt about the effective aspect of the species,” explains Braby.

Generations of scientists will repeatly resort to the holotype in their investigation, so the specimen has to be accessible to the public.

“If we start to move it, the Taxonomy tissue collapses“.

If a taxonomic name or description is published that is not in accordance with the code, the scientific community will almost always identify problems and will reject the new invalid species. This diligence is crucial if you want to be a good taxonomist.

“At this time, we have two diametrically opposite issues: on the one hand, we are losing biodiversity at a phenomenal rhythm and, on the other hand, we are discovering biodiversity to an unprecedented scale,” says Braby.

It is strange to meet in the middle of a biodiversity crisiswhile technology and scientific innovation are opening the doors to the discovery.

“So if the taxonomy will advance in strides, we have to do it well,” says Braby. “We have to learn from our mistakes and try not to repeat them.”

Teresa Oliveira Campos, Zap //