May not have been the judgment by tax evasion of the century – of the second century, of course – but it was of such gravity that the defendants faced accusations of counterfeiting, tax fraud and fraudulent sale of slaves. Tax evasion is as old as their own tax, but these particular offenses were considered so serious under Roman law that penalties ranged from heavy fines and perpetual exile to forced labor in salt mines and, in the worst, cases, damnation to beasta public execution in which the convicts were devoured by wild animals.

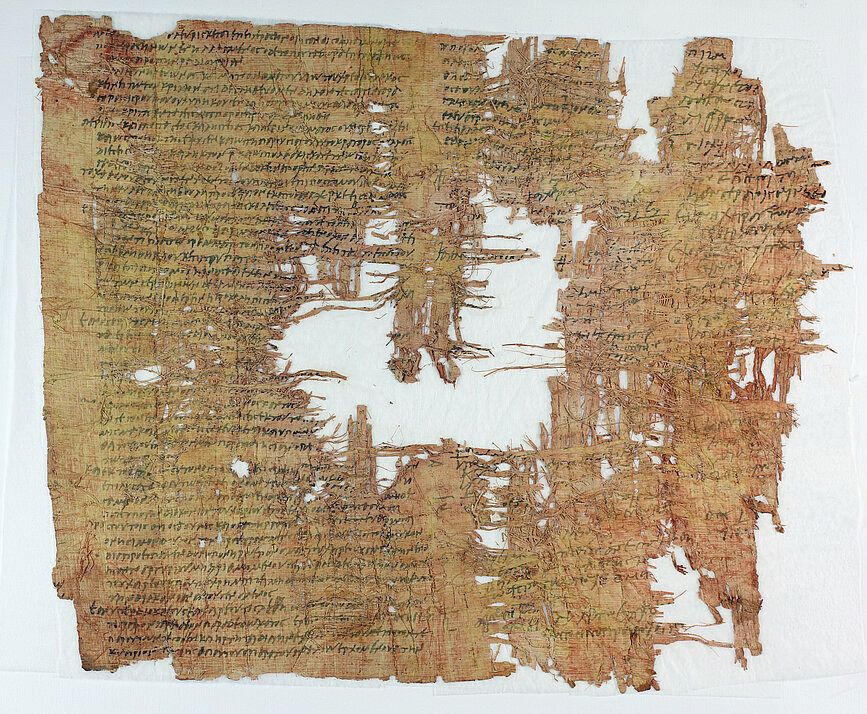

The allegations are arranged in a papyrus which was discovered for decades in the Judea Desert, but only recently analyzed; It contains the preparation of the prosecutor and the hasty minutes of a judicial hearing. According to the old grades, the tax dropout scheme involved the document falsification and Sale Sale and Liberation of Slaves – Everything for Avoid payment of taxes In the distant Roman provinces of Judea and Arabia, a region that corresponds to approximately what is today Israel e Jordan.

Tax evasions were Gadasia and Saul. Gadalias was the impoverished son of a notary with ties with the local administrative elite. In addition to condemnations for extortion and falsification, his catalog of crimes included banditry, insurrection and, on four occasions, the lack of jury in the Roman governor court. Gadaliah’s crime partner was Saulos, his “friend and collaborator” and the supposed mentor of the plot. Although the ethnicity of the accused is not mentioned, they are supposed to have Jewish origin, based on their biblical names, Gedaliah and Saul.

This old legal drama unfolded during the reign of Adriano, around the again 130 and presumably before 132 – that is, 1,893 years ago. This year Simon Bar Kochba, a messianic guerrilla chief, led a popular revolt – the third and last war between the Jewish people and the Empire. The revolt was violently repressed, with hundreds of thousands dead and most of the surviving Jewish Jewish population, which Adriano renamed Palestinian Syria.

“The papyrus reflects the suspicion that the Roman authorities saw their Jewish subjects,” said Anna Dolganov, historian of the Roman Empire at the Austrian archaeological institute, who deciphered her parchment. She noted that there is archaeological evidence of coordinated planning of the Kochba Bar Revolt. “It is possible that tax makers like Gadalia and Sauls, who were inclined to disrespect the Roman order, were involved in the preparations,” said Dolganov.

In the current edition of Tyche, an antiquity newspaper published by the University of Vienna, Dolganov and three Austrian and Israeli colleagues present court proceedings as a case study. Its article brings up how Roman institutions and imperial law could influence the administration of justice in a provincial scenario where relatively few people were Roman citizens.

Continues after advertising

Following the papyrus trail

No one knows for sure when or by whom the papyrus was discovered, but Dolganov said it was probably found in the 1950s by antiques Bedouin traders. She suspects that the scene of the discovery was Nahal Hever, a steep walls canyon west of the Deep Sea Slit, where some rebels of Bar Kochba, fleeing the Romans, took refuge in natural caves in limestone cliffs.

In 1960, archaeologists found documents of the time in one of the Jewish hiding places; Others have been discovered since then. Initially poorly classified, the Rapped Parchment of 133 Lines He remained unnoticed in the archives of Israel’s antique authority until 2014, when Hannah Cotton Paltiel, a classicist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, realized that it was written in ancient Greek. Given the complexity and extraordinary length of the document, a team of scholars was formed to perform a detailed physical examination and cross names and places with other historical sources.

Decipher papyrus and rebuild its narrative Intricted presented great challenges for Dolganov. “The letters are tiny and densely packaged, and the Greek is highly rhetorical and full of legal terms,” she said. “We only have the second half, or less, of the original,” said Dolganov.

Continues after advertising

The researchers say they had to put themselves in place of those involved with the case to understand what the papyrus said, both the Roman tax administration and the accused of the crime. “To commit tax fraud with the slave trade in the most remote corner of the Roman world, what would you have to do and what would make the effort profitable?” Says the researcher.

The old scheme resonated deeply with modern tax lawyers. A German lawyer told Dolganov that The gadiac and saul’s gadds were not very different from the most common forms of tax fraud today – Movement of assets, false transactions.

The case against Gadals and Saulos was strengthened by information provided by an informant who warned the Roman authorities – and the text suggests until the informant was no other than Saulos, who denounced his accomplice chaere to protect himself in an imminent financial investigation. The most likely scenario, said Dolganov, was that Sauls, resident of Judea, organized the false sale of various slaves For Chaereas, who lived in the neighboring province of Arabia.

Continues after advertising

Upon being sold beyond the provincial border, slaves would have disappeared in the records of Sauls in Judea. But as they physically remained with Sauls, the supposed buyer, chaere, could choose not to declare them in Arabia.

“Thus, on paper, the slaves disappeared in Judea, but never arrived in Arabia, becoming invisible to Roman administrators,” said Dolganov. “That way, all taxes on these slaves could be avoided. ” The Empire had sophisticated systems to track slave property and collect various taxes, which totaled 4% in slave sales and 5% in liberation.

“To free a slave in the Empire, you had to present documentary evidence of the current and previous property of the slave, which had to be officially registered,” said Dolganov. “If any documents were missing or seemed suspicious, the Roman administrators would investigate.”

Continues after advertising

To hide the double negotiation of Saulos, Gadalia, the son of the notary, evidently falsified sales notes and other legal agreements. When the authorities learned of the matter, the defendants allegedly made payments to a local municipal council for protection. In the trial, Gadaliacs blamed his late father for falsifications, and Saulos attributed the liberation of slaves to chaereas.

Papyrus offers no vision about its reason. “Why men have risked freeing a slave without valid documents remains a mystery,” said Dolganov. One possibility is that by falsifying the sale of slaves and then freed them, Gadasia and Saulos were doing a Jewish biblical duty to free enslaved people.

Or perhaps there was a profit to capture people-perhaps even willing participants-across the border, bringing them to the Empire and then releasing them from their “slavery” to become free Romans.

Or perhaps gadds and Sauls were traffickers of people, simple – Dolganov emphasized that alternative stories were entirely speculative, for nothing in the text supported them. What surprised her most about the trial, she said, was the professionalism of the prosecutors.

They employed rhetorical strategies of Cicero and Quintilian, and demonstrated excellent mastery of Roman legal terms and concepts in Greek. “This is the edge of the Roman Empire, and we see high -level legal professionals, competent in Roman law,” said Dolganov.

The papyrus does not reveal the final verdict. “If the Roman judge was convinced that these were criminals and the execution was necessary, gadals, as a member of his local civic elite, may have received a more merciful death by beheading,” said Dolganov. “Anyway, almost anything is better than being eaten by leopards.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.