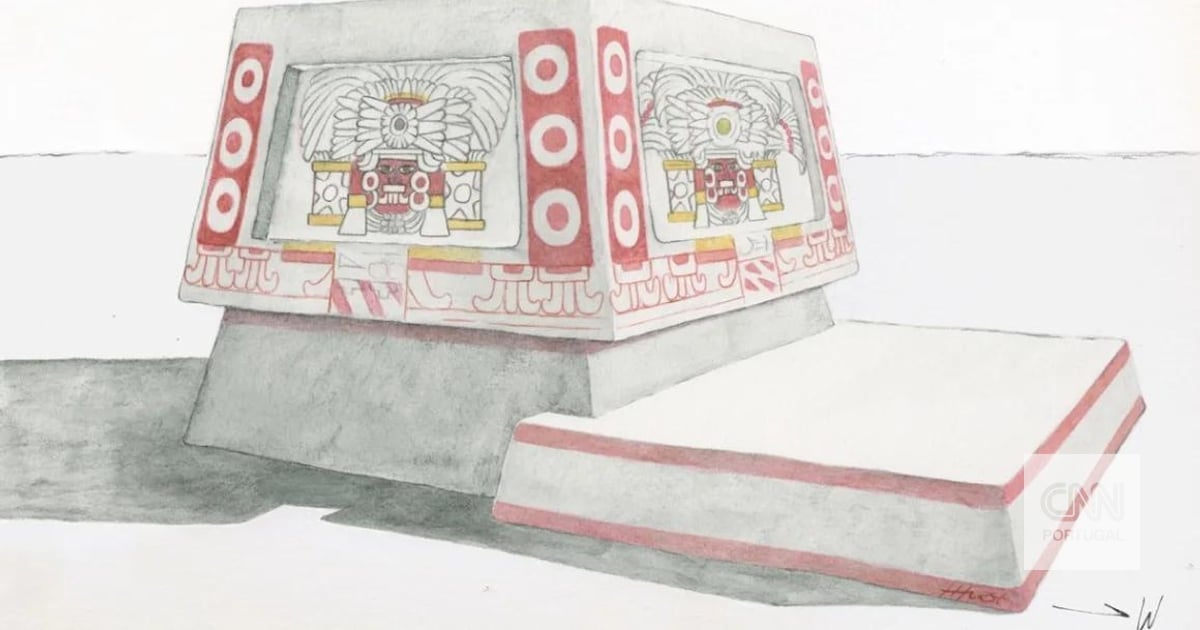

who worked in an old discovered a mysterious 1700 -year -old altar whose vibrant colors and macabre content can be the key to unraveling the complex geopolitics of the time.

Although the altar was found in Tikal, a ruined Mayan city located in the present Guatemala, archaeologists believe it was not decorated by Maias. Instead, they claim that it was the work of artists formed 1015 kilometers from there in Teotihuacan – a powerful city near the present city of Mexico, who had a strong influence on the region.

The altar still retains traces of the decorated paint (Edwin Román Ramírez)

Prior to this discovery, published in the magazine, archaeologists already knew that the two cultures interacted, although the nature of this relationship was the target of debate.

However, the richly decorated altar, with two bodies buried underneath, confirms that “wealthy leaders of Teotihuacan went to Tikal and created replicas of ritual facilities that would exist in their hometown,” says Stephen Houston, a professor at Brown University and a specialist in Maia, co -author of the study.

“It’s a story of Empire – how powerful kingdoms sought to control others,” he says. “This new discovery gives a strong weight to the idea that it was not just a mild contact or trade. It involved belligerent forces to build an enclave near the local royal palace.”

Stephen and the co -authors, the United States of America and Guatemala, began excavating the site in 2019, after archaeological surveys in the area revealed structures under what was once thought to be a natural hill.

“Only part of this palace is visible to the surface. The rest, especially the deepest layers, is only accessible through tunnels excavated by archaeologists,” Stephen explains to CNN. “We usually find a floor and walls, and we followed, thus exposing the buried buildings.”

Stephen Houston (left), photographed on archaeological excavation with Edwin Román Ramírez, co -author of the study (Edwin Román Ramírez)

During the investigations, the researchers discovered the altar, which still has outlines of a figure with a feature headdress on each panel and traces of red, black and yellow paints. This design resembles other representations of a deity known as the “God of Storm”, more common in Teotihuacan than in Mayan art.

Two bodies were buried under the altar – probably a male adult and a child aged 2 to 4, buried in a sitting position, again something more common in Teotihuacan than in Tikal.

The bodies of three other babies were found around the altar, buried in a similar way to other children’s tombs in Teotihuacan. The authors did not specify the causes of deaths.

“The altar confirms that Teotihuacan rituals were held in Tikal’s heart, involving people who used totally foreign painting styles, from Teotihuacan, to represent foreign deities as well,” says Stephen.

Some of the remains may belong to Mayan individuals, according to the teacher, “but the findings in the tomb suggest a close contact with, and perhaps an origin in, Teotihuacan. Children’s sacrifices fall into Mexican practices.”

These cultural practices point to a growing influence of Teotihuacan in Tikal, according to researchers.

And the fact that the buildings were later buried and never rebuilt “probably reveals ambivalent feelings that the Mayans had about Teotihuacan,” adds co -author Andrew Scherer, professor of anthropology and archeology at Brown University.

“The Mayans regularly buried buildings and rebuilt over it,” he says. “But here they buried the altar and the buildings around and simply left us like this, although it is a valuable terrain centuries later. They treated it almost like a memorial or a radioactive zone.”

This new discovery reveals another layer of the complex relationship between the two cultures that recent research has been unraveling.

In the 1960s, investigators found a stone with an inscription that described a conflict between the Mayans and Teotihuacan, and found that “around 378 AD, Teotihuacan was essentially beheading a kingdom,” recalls Houston.

“They removed the king and replaced him with a timore, a puppet king who proved to be a useful local instrument for Teotihuacan,” he adds.

This altar was built around the same height of the coup, explains Andrew, which would propel the Mayan kingdom to its peak before declining around the year 900 AD

The conclusions of this excavation show “a history as old as time,” says Stephen, referring to empires that compete and compete for cultural influence.

“Everyone knows what happened to Aztec civilization after the arrival of the Spaniards … These powers of Central Mexico arrived in the Mayan world because they saw him like a land of extraordinary riches, rare feathers of tropical birds, jade and chocolate. For Teotihuacan, it was the land of milk and honey,” he concludes.