The “bone hunter” slides to a thin slit in a hill in the Okinawa jungle. He is a lean man who wishes to the cave entrance, carefully avoiding the pointed limestone roof as he sails the ruined stone and the earth on the cave floor.

Scake yourself as the lamp on your forehead illuminates the earth at your feet and scratches the ground with a gardening tool, trying to find the remains of people who hid in caves like this during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II.

This is the work of the life of the bone hunter Takamatsu Gushiken. Takamatsu Gushiken spends much of his free time in caves like this in Okinawa, the southernmost province of Japan, trying to find an outcome for one of the fiercest, deadly battles of the Pacific War.

I ask you why he does this work. He pauses and shruggs.

“They are human, and I’m also human,” he says softly, looking down, his voice embargoed by emotion.

Gushiken shows me what he has found so far in this place – portions of a skull in the ear zone, smaller bones, perhaps one foot, he says, and even smaller, possibly a child or baby.

He also found a bullet and theorizes about what may have happened in this place eight decades: a mother and a child hid as the battle was out there. While American troops tried to clean the caves of hidden Japanese defenders, the two civilians, like so many others in Okinawa, were caught in the crossfire.

It would be among the approximately 240,000 people killed or missing at the Battle of Okinawa, from the disembarkation of the US invasion force on 1 April 1945 to the Americans’ victory statement on June 22.

This number includes about 100,000 civilians, 110,000 Japanese soldiers and Okinawa recruits and more than 12,000 American and Allied soldiers, according to the National World War II Museum in Luisiana, United States.

These lives were lost in an infernal scenario of overwhelming American firepower. US forces used 1.1 million 105mm obuses on the island, spent more than half a million mortar projectiles and fired over 16 million machine gun projectiles and 9 million shotgun bullets, according to the museum.

Shocker

Eighty years later, the scars remain, allowing visitors to approach and touch history.

On IE Shima’s coastal island, the hull of a pledge store is still standing. It is the only structure that survived combat on this 23 -square -kilometer island that housed an important landing track during the war.

After the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, the only structure that was left on the island of IE Shima was his pawn store. Still today shows the scars of war. Brad Lendon/CNN

In TomiguSuku, the shattered walls are proof of a mass suicide. A memorial outside says: “The vice-mirror Minoru Ota and his 4,000 men committed suicide in this underground headquarters on June 18, 1945”.

Outside an unidentified cave, near Nanjo, a grenade for exploding rests near the entrance, next to a busy road. Inside, the pick marks of the construction of the cave are still soft, as it opens for a machine gun place.

Climb a way from the southern coast of the island, and stay by the entrance of the cave where the Japanese garrison commander in Okinawa, General Mitsuru Ushijima, committed suicide on June 22, 1945, while American troops approached underneath.

And on the rock near a jungle cave, Gushiken, the bone hunter, indicates where the shotgun and machine gun bulges left his mark.

The correspondence between 1945 and 2025

Soldiers of the 7th US Army Infantry Division protect themselves around the Tomori stone lion while observing the Japanese action in the summit in front of you during the Battle of Okinawa of World War II. The statue survived the battle and is currently in the same place and can be seen by the island visitors. Bettmann/Getty Images Archive

If you put a pin on your mobile phone maps in any of these places, go to and you can see exactly what this piece of land would have been during battle or on your aftermath.

The archivists compared photographs of surveillance and recognition of the US Army with the current landscape. Perhaps nothing can better illustrate this infernal landscape.

Kazuhiko Nakamoto is the driving force behind the archive collection, trying to document the story of the war years and the postwar.

It tells the story of how his mother, a 6 -year -old child in 1945, survived the separate battle of his parents and the care of his grandmother, who was moving along the southern part of the island looking for safe places while the battle was taking place.

“It was a miracle she survived,” he says, adding that his family was one of those who were lucky in Okinawa.

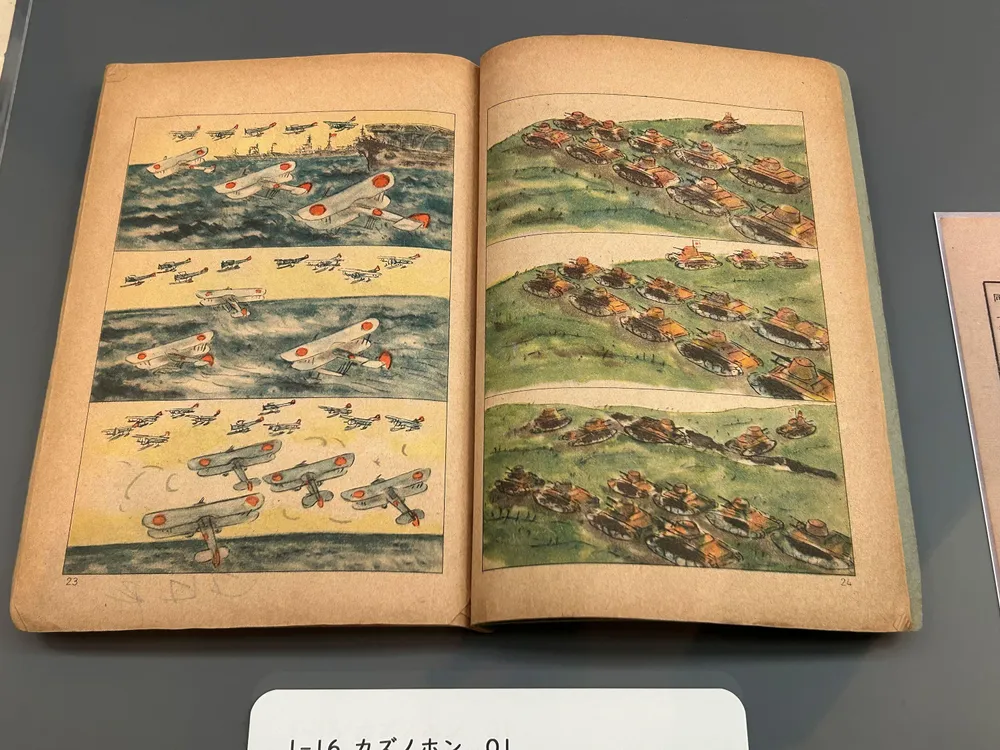

A textbook from the time of World War II, exposed in the archives of Okinawa City Hall, uses military images to teach elementary school students to count. Brad Lendon/CNN

Nakamoto and fellow archivists Akira Yoshimine and Eriko Nishiyama tell how Okinawa people were victims of a war that was not created by themselves. When Tokyo’s government raised the island, many thought that Japanese troops were there to protect them and not to enlist them in the fighting fights.

But militarism was uncertain even in primary schools, they say, pointing to a manual that taught students how to count on images of airplanes and war tanks.

School girls dipped in the war

No other place in Okinawa is more sensitive to this tragedy than the story of Himeyuri student body, teenage girls who were forced to serve the Japanese army during the battle.

The girls of the Okinawa Shihan Women’s School and Okinawa Daiichi Women’s Secondary School helped take care of the wounded Japanese soldiers in caves such as the one in the hint of the Museum that honors them, a rock hole known during the war as the third Ihara surgical cave, part of the Okinawa Army Hospital.

“Shortly after the battle began, Himeyuri students were mobilized,” says the museum. “The royal war proved to be unlike anything they had imagined.”

Surviving students tell the horrors who lived in videos shown in the museum.

They talk about helping to amputate members of the injured by performing operations without anesthesia. They say they removed larvae from the wounds, who tried to comfort those who raved “brain fever”, who saw their colleagues die under the US shots in the cave entrances or as they made refueling messages.

The entrance of the third surgical cave at the Himeyuri Peace Park in Okinawa. Brad Lendon/CNN

And they speak of a smell that pervaded the surgical caves – a mixture of human waste, blood, sweat and the rot of flesh – and never left the passages without ventilation. (Elsewhere, the army hospital deposit number 20 on the number, employees recreated this stench in a bottle and offer visitors a smell at the end of the visit. Even outdoors, it’s horrible).

Video testimonies are raw, vivid and difficult to listen to for a visitor.

After the videos, the portraits of the 227 Himeyuri that were killed or disappeared in Okinawa are hanging on the walls of a large room. A note under each of them tells their destination, several indicating the last time the girls were seen alive and that they are unaware of what happened to them.

These are the ones who affect me most and make me think of the bones that Gushiken had found in the cave where I was a few hours before. Can they belong to any of these young faces?

It is likely that we will never know the answer to this question. Gushiken says that from 1400 sets of remains recovered from caves and battlefatches, only six were identified.

He says he delivers everything he finds to the authorities, but it is to be determined to determine if it is possible to perform DNA tests.

Often there is not sufficient bone material to obtain a DNA correspondence, he explains.

If relics like pens or notebooks with names are found with bones, this can provide a track, he notes. But relics without this identification information are left where they are found.

Still, I would like to see the government to do more.

“I hope the authorities will adopt a more proactive approach to bone identification, improve their technology and return as many bones as possible to their families,” he wishes.

The Americans

If there is an American Gushiken equivalent in Okinawa, it may be Steph Pawelski. A native of Pennsylvania, the US military wife and a US Department of Defense Department professor is curator of the Facebook page.

The rear of its Subaru van is part library of the history of war, part warehouse of walking and speleology material. Your knowledge of the island seems encyclopedic.

One day of early March, I suggest we meet at the Hyatt Hotel, in the urban area of Naha, for lunch. Pawelski says we should arrive early and go see a cave in a park in front of the hotel parking lot.

During the exploration of a battle site on a slope with a team led by Gushiken, Pawelski advances in front of the group to indicate possible entries to the caves that the Japanese was looking for.

Pawelski says that his interest in battle sites is motivated by his grandparents, both served in Okinawa.

American Steph Pawelski and a colleague enthusiast of history exploit a military cave from the time of World War II in Okinawa. Brad Lendon/CNN

Using photographs that his maternal grandfather took during his time at Asian Theater, Steph Pawelski is trying to put himself in the exact places where his grandfather has been for decades.

“I was able to see through his grandfather’s eyes, follow his footsteps and feel his presence in a way I never waited. It was as if the past and the present had converged, creating an instant of the story in a way that words could never capture,” says Pawelski.

Minutes before starting the jungle with Gushiken, she makes a facetime so -called Florida with an Okinawa veteran, Neal McCallum, a naval Marine who landed on the island on April 1, 1945 and 49 days later he had a hole in the leg made by a Japanese bullet, a “one million dollars wound”, as he called her a ticket to leave the island. with life intact.

McCallum, now 98, will return to Okinawa to the 80th anniversary of the battle, and Pawelski is helping him make sure he sees what he wants, the places he says will bring him a final measure of “closing.”

McCallum says he got most of this during his first postwar visit in 2000.

“If I had some dark corners in my mind, I think they were eliminated,” he admits.

But his true change of opinion about the story happened during a visit to Osaka, 19 years earlier.

“I hated the Japanese intensely until 1981,” he assumes. For a few days in the second largest city in Japan, he crossed with some school-age children, eager to practice their English.

“They were telling me little affectionate gestures … ‘Hello, sir!’, ‘I love you’, or something like that. And I thought I am stupid for hating them,” says McCallum, adding that those who hate “won’t lead a good and healthy life.”

He also says he expects his visit to help to remember the current generation of the sacrifices of the so -called “greatest generation,” those who fought in World War II, and the legacy of what the Marines did in Okinawa.

Back to the cave site, Gushiken says he expects his work to send a message too.

“There are no more wars. There should be no more wars.”