Jorge Mario Bergoglio, an Argentine oblivious to the main papal pools, looked out to the Balcony of the Vatican Apostolic Palace in an Italian with a strong Porteño accent and a typical slyness of sacristy, presented his credentials to a Plaza de San Pedro crowded. “You know that the duty of the conclave was to give a bishop to Rome. It seems that my Cardinal brothers have gone to look for him at the end of the world. But here we are.” The end of the world was not just a remote place, but also a metaphor for how far his conception of the universal church of the postulates exhibited by their predecessors could be found. He announced revolution, passion and huge changes. Twelve years after his arrival, Bergoglio today could be said that the Holy Spirit has completed its reforms. And history and its successors will now mark the degree of irreversibility and depth of the transformation imposed by the 266th Pontiff of the Catholic Church.

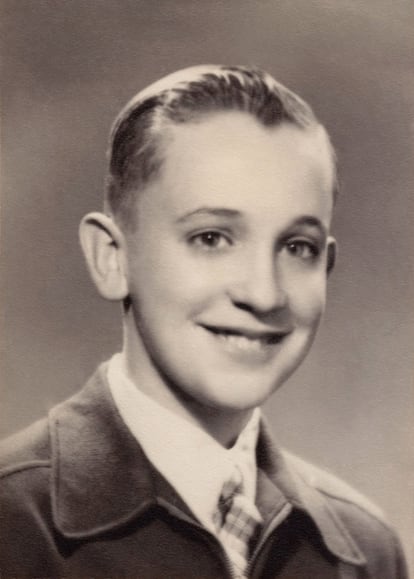

God does not fear changes, he always challenged his critics Bergoglio, an influential cardinal who knew how to alternate, as if it were a soft milonga, the power of the cachotes of the palaces with the sheep smell of the flock in the misery villas of Argentina until he was appointed pontiff. But if it is difficult to imagine how we will age, it should be impossible for a graduate in chemical sciences that began working in a food analysis laboratory in the mid -fifties in Argentina to think remotely that it could become the Pope of Rome. In March 1958, with 21 years of age, he opted for ecclesiastical studies and entered the Metropolitan Seminary of Buenos Aires, novitiate of the Society of Jesus. Francisco explained being Pope who joined the Jesuits “attracted by his condition of advanced force of the Church, speaking in military language, developed with obedience and discipline, and being oriented to the missionary task.”

On December 13, 1969, a priest was ordered and began a climbing process in the dome of the church that would end in Pedro’s chair. In 1971 he carried out the spiritual exercises and studies of his third test (final stage of the formation of a Jesuit) in Alcalá de Henares (Spain). In April 1973 he made the perpetual votes in the company of Jesus and in July of that year, Pedro Arrupe, general preposition of the Jesuits, appointed him provincial of the Society of Jesus in Argentina, a position he held until 1979. From there he lived the years of the military dictatorship after the coup d’etat of 1976 and his conduct was criticized in several in which his decision was released from collaboration. Five months of captivity and torture at the Mechanical School of the Navy (ESMA) in Buenos Aires. Bergoglio refuted these accusations in 2010, noting that he gave refuge to several people fleeing from the repression of the military. In an autobiographical book of conversations, entitled The JesuitFrancisco affirms that he did what he could “with the age he was and the few relations he had.” But that shadow would always chase him. Even, probably, when he made the decision to never return to his country.

His pastoral and intellectual career caught the attention of Cardinal Antonio Quarracino and thanks to his influence Pope John Paul II raised him to the episcopal condition at the Auca headquarters, in addition to becoming auxiliary bishop of Buenos Aires in 1992. From that moment, the rise of Bergoglio in the ecclesiastical hierarchy had no brake. In 1998, Quarracino succeeded as head of the Buenos Aires and Primo Argentino Archdiocese. The Cardenalicio Capelo was imposed by John Paul II in February 2001, in a ceremony in which another 43 new cardinals accompanied him. In 2005 he was appointed president of the Argentine Episcopal Conference, and since that position he maintained tense relations with the political power of Presidents Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Bergoglio, who always knew how to interpret the music that sounded at all times, was already in the popeable pools to the and there were speculation about the vote in the conclave that chose Joseph Ratzinger who pointed out that the Argentine cardinal obtained the second position in the final count. Eight years later, after a pontificate convulsed and marked by the scandals, the Cardinal College decided that he should bet on a change of course and that no one better than that Argentine to execute it.

Francisco’s main legacy, beyond structural reforms he undertook in the curia, will undoubtedly be the peripheral conception of the Church that he wanted to implement. The luxury was buried as soon as possible. Simple clothing, silver ring, austere shoes and residence outside the tinsel of the Apostolic Palace to share space with the nuns of Santa Marta. Poverty, marginalized and the disinherited of the world should be the gravitational center of their pontificate’s efforts. And Francisco knew how to better embodied that universe than him, to which he could attend in the front line as bishop of Rome, capital of a country where the great flows of the last decade passed.

In July 2013, anticipating everything that would happen later in that place, to cry to the victims of the shipwreck and celebrate a solemn mass on an altar built with the remains of a vessel on board which dozens of migrants died. An unusual gesture that would then repeat dozens of times with unrepeatable moments, such as his visit in April 2016 to a field from where he returned with 12 migrants on the papal plane. His revolutionary effort will undoubtedly remain as a true transformation of the Church. But he also opened several waterways with the ultraconservative world, which always affected him to be more concerned with members of other religions or the secular world than of the problems of Catholics. And that, in substance, was the great war he fought during his pontificate.

The idea of periphery was also marked by the 47 apostolic trips to 66 countries, which always sought to place the Vatican flag in world corners with threatened Catholic minorities or in full expansion: Bangladés ,, Congo, South Sudan, Japan, Mozambique, Madagascar, Philippines … His allergy to consolidated power, the western capitalist scheme, made him reject western Invitations to make a state trip to great powers such as France, the United Kingdom, Spain or Argentina itself, a place to which it avoided returning so as not to remove old issues and disputes from the past. But that idea of installing its church on the margins of the world was also forever printed in the preparation of the Cardinal College, the organ of greatest power of the Church and the instrument that must now choose the next Pope.

The conclaves, also in which Bergoglio was chosen in just two days and five scrutiny, used to be marked by the influence of the Italians and the richest churches: the German and the American. Francisco wanted to change that dynamic naming that naming pounding from remote places without apparent connections with the circles of power of Rome. The total number of cardinals has reached 252 and the voters are 138. From this select group, 110, 23 of Benedict XVI and 5 of John Paul II. The rest are non -electors, that is, over 80 years. In 2013, when the Argentine arrived at the Pontificate, Asia and Oceania had 11 electrical cardinals. After the last session, they reached 28 and even and where the percentage of Catholics is minimal, such as Eastern Timor, Singapore or Mongolia. A gravitational change that will generate a completely different geopolitical dynamic in the choice of its successor.

The change in the power scheme of the Church, Francisco’s great obsession, was the fundamental cause of his break with an important part of the dome, mainly in countries like the US. Bergoglio, with a reputation of progressive -the reality is that his speech on great issues such as abortion or homosexuality was not very different from that of his opponents -, he had to live together with an Emeritus Pope, to which the conservative sector made the theological correction and neatness. But also what a good Pope should be, although many of those same cardinals and bishops were responsible for his resignation in 2013.

Francisco was accused of heresy and a group of Cardinals raised a Dubia -aclarations- about Love happinessthe apostolic exhortation in which the door opened to allow communion to divorced men and women. But the war was increasing its violence, and an exarzobispo and ex -nunciation in Washington, Carlo Maria Viganó, requested his resignation publicly in an orchestrated and financed campaign from the US for an alleged cover -up of the abuse of Cardinal Theodor McCarrick. A prelate to whom, precisely, the Pope would later dispossess his rights as a cardinal and as a priest, returning him with a violence until then unusual to secular life.

Beyond the attempt to overthrew the Pope for reasons of power, Francisco had maintained a relationship with the fight against abuses somewhat intermittent. Although on his arrival he had launched a series of new measures, such as the creation of a pontifical commission for the protection of the minor, he did not seem that his papacy took the issue too seriously. Until he traveled to Chile in January 2018 and had a encounter with a journalist who reminded him of the case of the priest Fernando Karadima, a serial abuser. Francisco, with his spontaneous and something authoritarian nature, made a serious mistake: “The day they bring me a test against Bishop Barros, there I will speak. Not a single test against. It’s all slander. Is it clear?” The scandal was capital, but as was the case with Bergoglio, it was also the revulsion it needed to implement a process of reforming the prevention, control and sanction system for this matter.

The ten years of Bergoglio were accelerated, transformers and, to some extent, revolutionaries. But the unity of measure of the Church, an institution that survives and governs in the world for 2000 years, is the century. And well looked, it was a good idea that someone arrived from the end of the world so that everything changed as much as possible in the shortest time. Even if it was so that everything could continue the same.