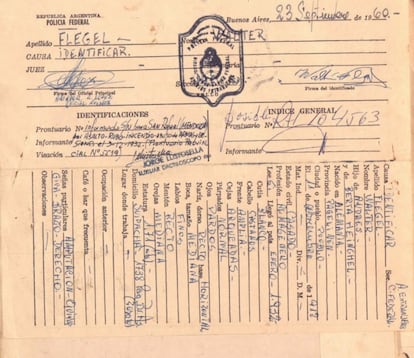

Walter Wilhem Flegel, born in 1912 in Pagelinen, Province of Instterburg, Eastern Prussia, temporary worker in a sawmill in Chile, imprisoned for theft for 11 years in the Argentine province of Mendoza and finally exemplary employee in a company in Buenos Aires, it was between September 23 and 30, 1960

Flegel’s story occupied the attention of the Argentines when the world was looking for in every possible corner to the Nazi hierarchs who had fled Germany after the fall of the third Reich. A mysterious list warned that this German of humble clothes was none other than Bormann himself, disappeared as a ghost on April 30, 1945 in the Führer’s bunker and reappeared tens of times in places as distant from each other as Moscow, Cape Town, Sydney or Bariloche, in the Argentine mountain range. Bumann was now hiding in a small wooden house raised with his own hands in Zárate, 100 kilometers from Buenos Aires, along with his wife and three small daughters, which he saw only once a week because he worked as serene in the sheds that Construcciones Claussen had in the capital.

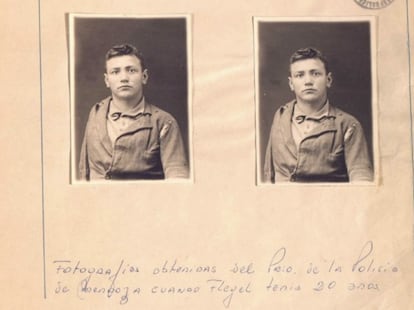

Flegel was famous for a week, very much, as attesting to the more than 100 pages dedicated to his detention that work in the archives of the Argentine Police on the Nazi issue, and available at the initiative of the Government of Javier Milei. Among the hundreds of documents, the photos of a skinny man and face full of bones, which poses with a combination of surprise and stupor to the camera. The police part of that day describes Flegel as a man who “expresses himself fluently and without inhibitions, revealing a median culture” and the “psyche of a common man.” “The palpebral cleft [la abertura del ojo] It is small, the brown eyes with a senile arch, the back nose something concave ends up in a tip reminding of a duck peak, it is medium -sized, ”wrote the police expert. With a little attention it is perceived that Flegel lacks the right arm.

The man who was Bumann had arrived in Chile in 1930 “as crew of a 10,000 tons loading ship” and dedicated himself to “rural tasks.” “It was in those functions when in July 1931 the transmission strap of a mill tore his right arm in its entirety,” says the police. Given the difficulties in Chile, Flegel crossed the Andes mountain range to Argentina, “doing it to horse back,” to the province of Mendoza. “It was there that his situation became unsustainable, cause for which he had to commit subsistence. On one occasion, in April 1932, he intended to steal a trade and was discovered by one of the caregivers, whom he injured using the revolver,” reads one of the declassified documents.

Flegel was imprisoned until 1935 and, already in freedom, “a horse stole.” “The owner attacked him to rebors and Flegel defended himself with a revolver.” Condemned to six years in prison, he left in 1943. Flegel’s life was since then that of a nomad who earned a living as a street vendor until, in 1944, Construcciones Claussen hired him as serene. Sent by the company to Corrientes, on the border with Brazil and Paraguay, Flegel met Haydee Colinett, a 16 -year -old teenager with whom he married in 1947 after “having obtained the corresponding permission from his father.” In 1948, Flegel finally settled in Zárate, in the house where 12 years later he would be arrested by two civilians. In his statement, he told the Police that “he only dedicates himself to work, not attending meetings, clubs, nor does he frequent the friendship of the neighborhood or with national ones.”

The Argentine press became a feast with the false Bormann. Today we know that the Nazi hierarchy had been dead for 15 years when Flegel fell imprisoned, but then his arrest put the democratic government of Arturo Frondizi before the eye of the world. The diplomatic messages sent by Germany to Buenos Aires are evidence of the interest that aroused the case. The common sense, however, worked in favor of the detainee: although his face could lead to some confusion, “it would have been easy for the police to determine that Flegel was not Bormann only taking into account that the former is 48 years old and the second 60”, he wrote in an editorial the newspaper El Diario The reason.

From Germany the testimony of a sister arrived, while the Israeli sensational press assured that there was no doubt that in Argentina they had caught Bormann. The newspaper The reason He revealed from Argentina, “based on sources that leave no doubt”, which Bormann frequented a bar of Lavalle 545 street in the city of Buenos Aires. “There, the brown eminence, the man in whom Hitler deposited his trust, while hurrying his favorite drink, beer, filed a conversation with other hierarchs of the third Reich, including Adolfo Eichmann.” The testimony of Eichmann, who did live in Argentina, was, according to the press, where the track had come out to find Flegel, a fact that the Israel government took care of denying.

The “unable” source turned out to be an Italian doctor who had met Bormann in Munich and told The reason that he had seen him several times at the Bar on Lavalle street, which he wore “elegant” and that “he had his artificial right hand with a black leather glove covered.” The newspaper topped the text regretting that Argentina would have been “Nazis refuge, covered by powerful characters.”

In the absence of social networks, Zárate neighbors were responsible for giving wings to all kinds of false news. In a box entitled Doubtsa special envoy said that “some dark details” suggested that Flegel, although it was not Bormann, “it could be an individual linked to the Hitler regime.” The journalist then quotes neighbor Moisés Fridman: “Police came on Friday to protect Flegel, who was already surrounded by Israeli commands. They knew his whereabouts for the delation of Eichmann.” A H. García, a public hammer, said that in 1952 Flegel’s wife told her that her husband had belonged to the battleship Graf Spee and that “that is why he was prohibited from entering the country.” On December 17, 1939, when Flegel had already been in Argentina for almost a decade.

“Bormann’s dactyloscopic dates are not yet [llegarían desde Alemania recién a finales de noviembre]but it can already be established in a concrete way that Walter Flegel is not Martin Bumann, ”said Interior Minister Alfredo Vitolo on September 30, 1960. The main argument was that Flegel has been in Argentina since 1931. The political repercussions began then. In an editorial dated October 5, the newspaper Argentinemianes tagletsedited in German in Buenos Aires, he wondered “why the bluff has been committed” to arrest Flegel. The newspaper stressed that the capture had been based on “a list of 20 names of Nazi -resident war criminals in Argentina” delivered to the government. “And Flegel was consciously chosen from those 20 names by certain people who had no ear to stop true Nazi war criminals,” the newspaper complains.

On September 30, 1960, Flegel finally was released. They were waiting for him at the door of the Federal Police Central “The engineer Claussen”, who had always defended the innocence of his employee, and dozens of journalists. Stunned by the questions, Flegel said he had met Hitler “during a meeting in Allestein in 1927, but then nothing more”; that only German and Spanish “badly”; and that he did not return to Germany because he did not have the means to do so. The next day, the Argentine newspaper The worldalready disappeared, thus closed his chronicle of the day: “Yesterday, Flegel, modest worker forged at work, returned to his department manager routine in the Alsina 465 building, by Claussen and Cia. It may be a desperately monotonous routine, but tranquility and anonymity are sometimes unappreciable gifts.”