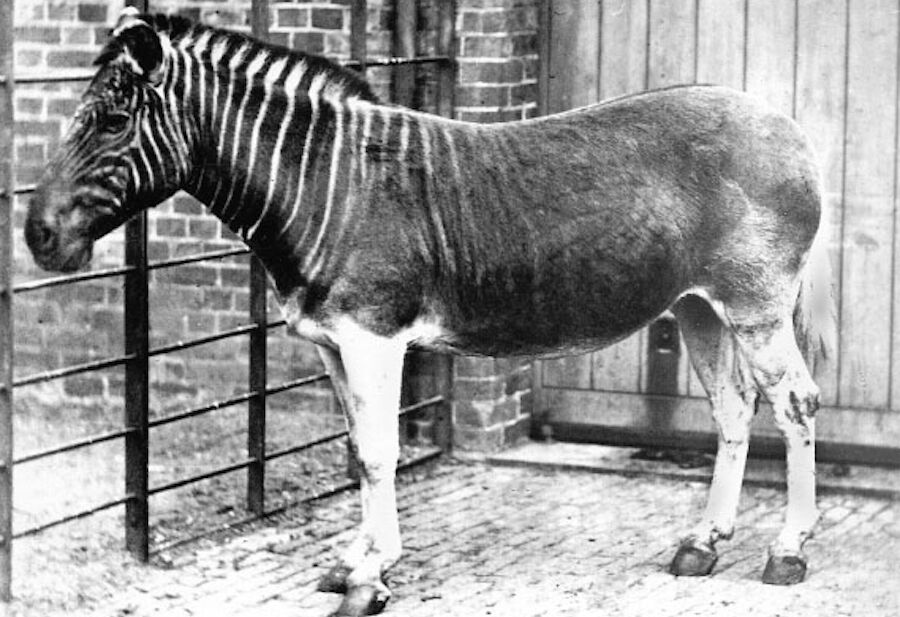

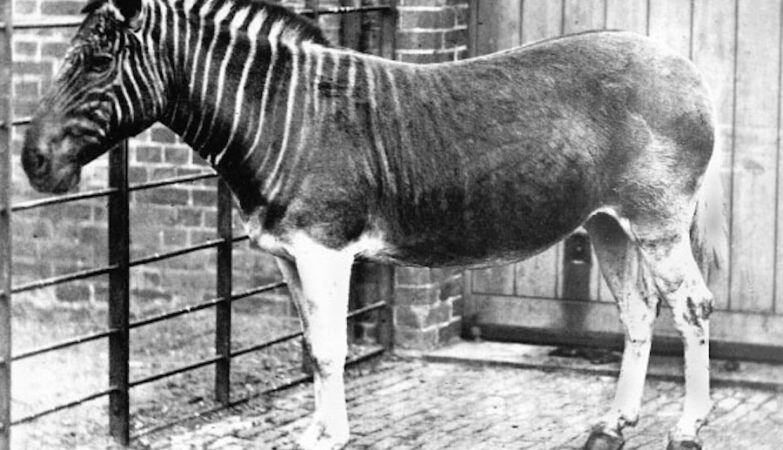

The only specimen of Quaga (Equus Quagga Quagga) photographed in 1870.

It was very similar to the common zebra, but striped only in the head and neck-a pattern that faded into a solid brown on the body. It was also more docile, which in a way dictated its end.

There is no one living who has seen the quaga (Equus quagga quagga) alive. The once prosperous subspecies of the zebra of the plains ran through the temperate prairies of South Africa, in large family herds, of 30 to 50 animals.

It was more docile than other zebras species, which also led to their recognition as subspecies, along with their distinct. But this personality trait may also have dictated to its end.

Like the modern zebras, they were herbivores: they lived on herb, vigilantes against predators such as lions and chitas. At night, at least one member of the herd was awake to watch over the area. The males were polygamous, led the harens, and sometimes conflicted with rivals by dominance.

Quaga was another victim of excessive hunting and loss of habitat provoked by human exploitation. The European settlers valued the quaga for both their flesh and their skin, which they often turned into leather. Farmers saw the animal as a competition by pasture and began to systematically remove them from the landscape.

Tragically, his decline has practically unnoticed due to confusion with other zebras subspecies. The term “quaga” was once used to describe all zebras, which shot conservation efforts in the past. When humans realized that these animals were unique, it was too late.

The subspecies disappeared from nature in the nineteenth century. The last known quaga died in a zoo in 1883.

More than a century later, Science began to try to bring back the quaga. After discovering, in the 1970s, that the animal was a subspecies of the Zebra of the plains, still alive, the Quagga project was created in 1987 in South Africa to put it back on pastures through selective reproduction.

Scientists took the zebras from plains that naturally display similar characteristics to the Quaga and began to reproduce individuals along successive generations, hoping to resurrect their unique appearance. Over time, the animals that resulted from the program became increasingly similar to the extinct subspecies, but like all selective reproduction projects, some stand back.

The most negative critics of the Quaga recovery process argue that the result may be a different color zebra, not a true genetic recreation of the original quaga.