It was still morning when a crowd of sleepy students – all with equal uniforms and impeccably identical hairstyles – aligned with the daily gathering next to the flag mast at his Bangkok Secondary School.

Baramee Chaovawanich, an eighth grade student, was among the 3,600 students present when the teachers traveled each line, examining all adolescents in a monthly verification of the fulfillment of the clothing and appearance code.

It was then that a teacher pointed to Baramee Chaovawanich, known for the nickname “Khao Klong”, and said his hair was too long. Ashamed, the boy was forced to come ahead and have his head partially shaved in front of the entire school, with the teacher deliberately cut the cut for Khao Klong to use it that way for the rest of the day.

“I was very ashamed. I was a child and was transformed into a joke, isolated, and they shaped my hair so that I was ugly on purpose,” recalls Khao Klong, now 20 years old and at the university. He vividly remembers having returned to class later, where “everyone turned to me and untied to laugh.”

“It was a scene that was recorded in my memory, and it made me very insecure,” he confesses.

Punishment may seem extreme, but for decades, such situations have been common throughout Thailand, with students being subject to strict rules on their appearance that go far beyond school clothing codes from other countries.

For example, male students had to have military -style haircuts, and female students had to wear short cuts up to their ears – until the rules were softened in 2013 (when boys could grow their hair to the neck, and girls could make it even longer, as long as they were caught).

Khao Klong’s hair was just a few inches above the limit, but even that was considered too much.

A Thai barber sharing a student’s head near a Bangkok school on July 31, 2013, shortly after the government relieved the rules on student hairstyles (pornchai kittiwongsakul/AFP/Getty Images)

However, the rules on hairstyles are significantly changing. In March, the highest administrative court in the country annulled the directive, established by the Ministry of Education in 1975, declaring it unconstitutional.

The rules “impose excessive restrictions on personal freedom”, thus violating the Thai Constitution, says the court decision. The decision added that the 50 -year -old regulations were “not aligned with contemporary social conditions” and impaired children’s mental health during ages of great development, especially those with various gender identities.

The court ruling had long been expected, after the 2020 student protests across the country had brought the issue to the center of attention and led the Ministry of Education to let each school decide their own rules.

The decision was enthusiastically received by some students, who had long wanted to express themselves freely through their appearance.

“Things have changed, especially (how) they checked their hairstyles,” says Nijchaya Kraisriwattana, 16. Her school in Bangkok used to do weekly inspections to the students’ appearance, and Nijchaya had already lost academic points for having too long hair.

The rules were so rigid that it really had to arrest the bangs back and hide the rebel hair around the face, but nowadays the rules seem “more relaxed,” he explains.

However, concerns persist between those who fear that some schools continue to impose rigorous guidelines and severe punishment without government intervention.

“Initially, I was happy when I read the news of the decision, but then people started analyzing it well. It seems that there are still gaps, which makes me a little worried because it does not seem much different from before,” says Khao Klong. This young man and other student activists “have not seen many changes to happen yet,” he adds.

CNN contacted the Ministry of Education for comments.

Although it may be difficult to understand why the rules were so rigid, reflect the conservative and hierarchical Buddhist society of Thailand and a culture born of many years of authoritarian government.

The influence of the army is deep in Thailand, a constitutional monarchy who suffered a dozen successful blows since 1932 – the latest in 2014. The rules of the students’ clothing code were written by a military government under the dictatorship of a decade of Thanom Kittikachor, which was deposed by violent revolt in 1973.

But the conservative influence of the army on how students should present themselves at school persisted to this day, explains Thunhavich Thitiratsakul, a researcher of educational policies at the Thailand Development Institute, which he has written about the policy of the clothing code.

“It is a social norm, the social value is that students have to obey the law, and if they behave well, they become good people,” he says.

In Thailand, “students have to hear their parents and follow the school’s regulations,” he adds. “If (they) get a job in the future and know how to follow the rules it means that they are good people and tend to do well.”

The court order acknowledged this way of thinking, stressing that hairstyles regulations aimed to “cultivate students as future citizens, emphasizing the need for close supervision by parents and teachers to ensure that they followed the norms and laws of society.”

This military-style education extended to other forms of discipline. Khao Klong recalls to be beaten by teachers almost “every day” in basic education for “lack of discipline, sometimes with a ruler until the object broke. The rules were also strict about uniforms, similar in all public schools, specifying even the types of socks and shoes that students should wear.

Over time, students began to react. But even the slowdown in the rules in 2013 generated controversy with some parents and teachers to argue that more flexible regulations would encourage disobedience and distraction.

The debate continued until protests broke out across the country in 2020, with a group of students deciding that it was time for things to change.

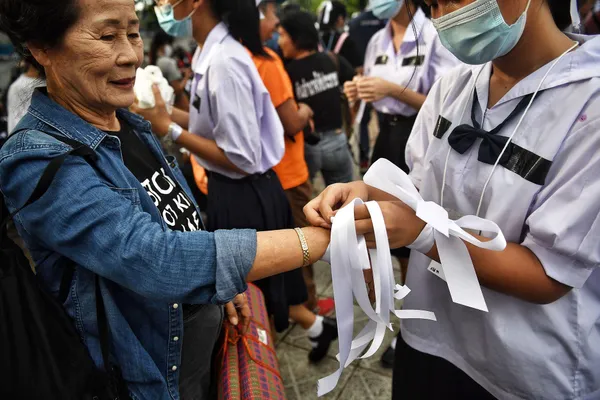

A secondary education student puts a tape on a wrist of an elderly protest during a protest for the reform of the education system and against the Thailand military government in Bangcoque, September 5, 2020 (Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP/Getty Images)

‘Bad students’ counterattack

Throughout the country, tens of thousands of pro-democracy protesters took to the streets, demanding reforms to the constitution written by the military and the powerful monarchy. The protests were notable for challenging old taboos and criticizing the royal family – which, according to Thai laws, is punishable by prison.

As the demonstrations extended to summer and autumn, the students also acted. Basic and secondary students promised to reformulate the clothing code and the regulations about hairstyles, as well as reform what they called the abuse of power by teachers and administrators.

The two movements were distinct, but student protests may have been influenced by the broader pro-democracy manifestations, he considers Thunhavich Thitiratsakul. Photographs of student protests showed hundreds of adolescents to adopt many of the visual symbols used in the pro-democracy manifestations, such as the gesture of lifting three fingers and the yellow rubber ducks. “Our first dictatorship is the school,” read in some of the protest posters.

Khao Klong was one of those students. His experience with the shaved head left a “mental scar” that he didn’t want anyone else to suffer, he explains. Therefore, he joined a coalition of activists called Bad Students.

Secondary education students raise three fingers, a symbol of resistance, during a protest in Bangkok, Thailand, on September 5, 2020 (Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP)

“Get rid of bitter and outdated uniforms!” Reads in a publication on the ‘bad students’ in November 2020, appealing to students to “dress as they want.” The following month, the group organized a protest in front of the Ministry of Education, where they hung their school uniforms at the gates.

The protests were colorful and animated by the students properly equipped. Some put black tape over their mouths to represent their feelings of oppression at school; Others used inflatable dinosaur facts, ridiculing what they called the older and outdated generation of Thai politicians who dictated their uniforms.

As a challenge, some cut their hair into the protests. A 19 -year -old, Pimchanok Nongnual, broke his hair on the Ministry of Education stairs and in front of a high employee at the time.

“What about the students with a fluid or non-binary gender?” Asked many rainbow-dressed students to demand more diverse uniforms in terms of gender.

“We felt hopeless. At that moment, it was like, if we are not, who will it be? In the sense that if we do not speak, who will speak for us?” Says Khao Klong.

The group presented petitions and complaints to the government, which led the Ministry of Education to revoke the hairstyles regulations in 2023 to ensure that “they do not limit students’ bodily freedom.”

Last year, the ministry also advised schools and teachers to be cautious when applying punishment.

A protester hangs school uniforms at the Ministry of Education gates during a manifestation of the ‘bad students’ movement in Bangcoque on December 1, 2020 (Mladen Antonov/AFP/Getty Images)

The recent order of the court seems, at least on paper, cement these victories, and by declaring the “unconstitutional” hairstyle rules, you can give students more power in schools that choose to maintain stricter rules.

Nijchaya Kraisriwattana, the student of Bangkok, felt the change when he recently arrived at school without arresting the bangs behind. “They just let me go without saying anything,” he recalls.

When they asked him if he wanted more freedom in his clothes, he answered effusively, “Yes, absolutely.” He said he liked to wear t-shirts and ganga pants and to be able to make his hair loose.

But Thunhavich Thitiratsaku considers that it is still early to celebrate. “Schools now need to be held responsible and consult their communities and school councils on how to adjust their regulations,” he says. However, it is unclear whether students will take place at the table.

Five years after the protests, students who were on the front line are tired. Many followed with their studies, dealing with the demands of school work, jobs and everyday life. The issue of student rights has disappeared from headlines, although obstacles persist.

Still, Khao Klong states: “With this court decision, I hope we can again discuss rights and freedoms in all schools, issues of oppression or authoritarianism.”

“Just because we didn’t talk about it doesn’t mean it disappeared; we just forget to approach it,” he adds. “We feel that the desire to fight may have diminished, but we still remember the sense of threat when we raised to fight for our own rights.”