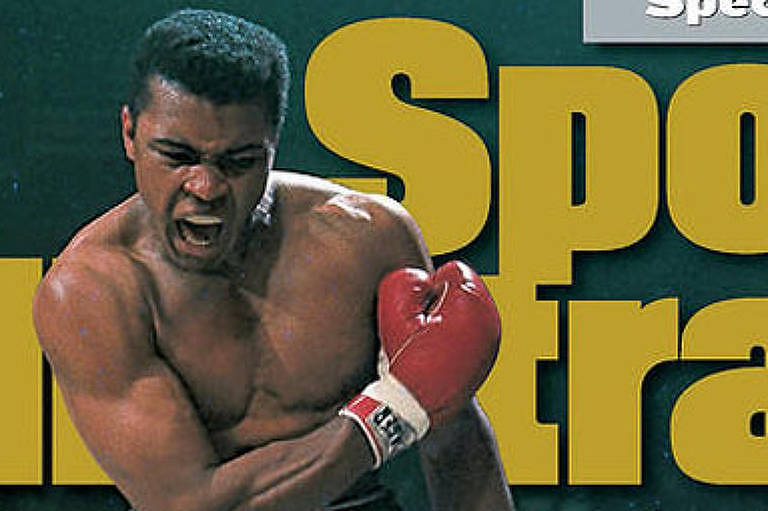

When Muhammad there hit Sonny Liston with a right -hand straight one -minute and 44 seconds from the start of the title fight on May 25, 1965, some things happened in a rapid succession: Liston went to the ground. There he stopped over him, shouting, “Get up and fight, sucker!” And amid the snap and brightness of the flashes, Neil Leifer, a 22 -year -old freelance photographer who worked for Sports Illustrated, squeezed the shutter of his camera.

His image Ali – feet, with severe expression, shaking his arm over the defeated Liston – did not go out on the cover of the magazine. Nor was it used at the opening of the report. It was published on the last page and then forgotten in a file of the photography editor. And yet, now 60 years later, Leifer’s photo is considered by many to be the greatest sports image of all time.

Still surprisingly, the image that comes to mind when we think of there – one of the most photographed athletes in history – was made on a hockey track of a Youth Center in Lewiston, Maine, against less than 4,000 fans. Even more surprising is that Leifer’s photography has gone over the iconic.

Here, Leifer, now 82, who took her first photo for Sports Illustrated the day she turned 16, talks about how the image came to her life.

This interview has been edited for size and clarity.

Let’s go back 60 years, for the night of the title of the heavyweights in Lewiston. Some of the largest magazines of the time sent their most renowned photographers. Why was Neil Leifer, only 22, was cast?

I was no longer a beginner at that time. In 1965, I had already made 15 covers for Sports Illustrated. At the time, many covers were illustrated, with paintings or caricatures, and I probably got one in two available for photographers. I had also photographed the first fight between Cassius Clay and Sonny Liston in Miami [15 meses antes]When we had five photographers – all my heroes: Hy Peskin, Marvin Newman, Ralph Morse, Bob Gomel. And I got the cover. In Lewiston, we had two precious seats on the edge of the ring. Herbie Scharfman got one, and me with the other.

In his photo, his colleague from Herb Scharfman magazine appears among the legs of Ali, clearly losing the moment. How was it decided that Scharfman would be on one side of the ring and you on the other?

It was his choice. He liked to sit in the middle of the ring [ao lado dos juízes] Because if you are in a seat like what I was, you shoulder to shoulder with other photographers and gets tight. But that made no difference. I always understood something about sports photography: the importance of luck. You need to be lucky. And I was lucky to be in the right seat that night. And when you are lucky, you can’t make a mistake. What happened that night was that I was very lucky, and I didn’t go wrong.

[Nota do repórter: o fotógrafo da Associated Press, John Rooney, posicionado à esquerda de Leifer, capturou o mesmo momento, mas sua imagem em preto e branco, embora muito divulgada, não tem o mesmo impacto poético ou força da imagem colorida de Leifer.]

When there and Liston fought in Miami, everyone thought Liston was invincible. The bets favored him at 7 to 1. Liston was seen as the solid boxer, from Estabishment, and there, then still Cassius Clay, like newbie and extravagant. For many, Ali’s victory marked a new era for boxing, sports and culture. Did this go through your head as you prepare for the rematch?

For me, this fight was nothing different. It was just another fight. For me, it was a payment. In fact, I entered thinking that no one would remember her. There he had won Liston so easily in Miami that anyone just knew that he would have no problems with Lewiston.

How did you prepare for the fight?

I probably arrived in Lewiston three days earlier to work with the electricians, which you usually had to bribe. Maybe not bribe, but when I started offering money, I could help you needed. I had two sets of flashes, perhaps about six meters above the ring, and the electricians needed to hang them in the right place and make sure they worked.

You used a medium -shaped Rolleiflex camera. Why?

Quality. There is no difference between the quality of my photo of Al-lyston and Richard Avedon’s in the studio. Second, I wanted the cover of the magazine, perhaps also the opening of the story. How to decide in a second fraction is photographed vertically or horizontally? One of the great advantages of Rolleiflex: the square frame. You don’t have to rotate the camera if you are thinking of a double page. You take the best photo and, if you cut well vertically, become an entire page or cover. If you cut well horizontally, it becomes a double page.

These white, black and red really jump to the eye. How did you get this effect?

You illuminate like a studio portrait. I think we were three with flashes. You want fighters to stand out and muscle tone is accentuated. It’s like doing a fashion rehearsal for Vogue: you choose a point in the ring where you think “here will be the best place to take action” and illuminates the subject there.

The framework has no visual distractions. He holds the look at the fighters.

Because there was no commercialization. The mat was a simple canvas, beige. Nothing in the shorts. Nothing in the gloves. The background would be different today, with all kinds of crap: Light beer ads, hotel …

But it is also the dark background. Talk about it.

Smoking was allowed, and at the time the public was 90% male, and many smoked cigarettes or cigars. Many cigars. The flashes crossed the smoke and created a slight bluish mist instead of a total black, which gave a more dramatic touch to the photo.

A lot of people call the blow that overthrew Liston “ghost punch” because they didn’t see the fast straight to hit him and assumed that the fight was armed. Did you see the blow?

They ask me this more than anything else. No, no one expected a two -minute fight, and I was focused on the equipment. But it is important to remember that Liston got up and they fought again. All he had to do was stay on the floor for another second and it would be over. But he got up.

Looking at the picture, we imagine that there was stopped on Liston for a couple or three seconds, but …

Until I saw the video some time later, that’s exactly what I thought.

But seeing the video and movement of Ali’s arm is a fraction fraction of a second. It hardly happens. Why did you click right now?

It’s not modesty: it was pure luck. My flashes took three seconds to recharge. Three seconds until I can take another photo. If there I had done something even more spectacular two seconds later, I would not have registered.

Knowing that I would have to wait three seconds for the next photo makes your decision to shoot even more amazing. Did you see there start to swing your arm?

You hope the action happens at a certain point. He knew that three meters from me, in the center of the ring, it was the perfect place. So I do two things, and nothing more: focus the camera – at the time there was no automatic focus – and I leave the flashes recharge. I knew the referee was not between me and the fighters. It all happened very fast, but I knew everything was where I wanted.

The composition is fantastic. There it is centered. It has the glory of victory and the pain of defeat. And it’s the only colorful photo of that moment. Did you know you had captured the right moment?

I had no idea. It happened so fast.

Today, your photo is considered by many to be the largest in the history of sport. But when the Sports Illustrated edition came out, she wasn’t on the cover.

I thought I had a very good picture and I was pretty disappointed that I wasn’t on the cover. But I didn’t think so much, and no one else thought either. The photo did not win a single prize. Zero. No honorable mention. At the time, I thought, “I was in the right place and took the picture.” But is this something that people would comment 60 years later? Not even a million years ago I imagined that.

[A foto de Rooney, sim, ganhou um prêmio importante da World Press Photo.]

How did your image go from ignored to iconic?

This is the young there, in the ring, in its best form. And he was handsome. A charismatic, confident subject, an incredible fighter, an extraordinary human being. This is how people want to remember there.

Lewiston was Ali’s first fight after changing Cassius Clay’s name. A lot of people didn’t like it. Then he adopted unpopular positions against the Vietnam War and civil rights. At the time, they were radical postures, but over time they became common sense. Did the culture take to reach the photo?

As the reputation and prestige of Ali grew, the importance of the photo has also grown. He became Muhammad there, this iconic figure that is today.

When you say he “became” Muhammad there …

This is the only explanation I have, because the photo itself is not special. I love the image, I am proud of it, and I thank God for being lucky to be in the right place and not missing the moment. But I don’t delude myself thinking it’s the biggest sports photo of all time, because I don’t believe it.

Why not?

If I had taken exactly the same picture in a preliminary fight with a beautiful black boxer – same look, same pose, same light – no one would have carried out. What makes the photo special is the subject. The image was very generous with me, but there is nothing in it that makes it a great photography. I’m just being honest. My favorite image is Ali-Williams, because it was not a matter of luck. It came from my head. This is the one that is hung in my house, and will continue there while I live.

[A imagem de cima para baixo de Leifer mostra a luta de Ali com Cleveland Williams, em 1966.]

You would still make 40 covers for Time and shoot Popes to Charles Manson. But it is by Al-Liston that you are known.

I made a lot of good photos, a lot. I made images that I consider iconic. But I don’t delude myself about how my career would have been if it wasn’t for that image.

Does the fact that this photo has gained new meanings over 60 years changes your vision about the life of an image?

I don’t think so much about this kind of thing. Always fun see how people are touched by this image. Sometimes weird come to me and say nothing, just cross their arm in the chest. I don’t criticize anyone for feeling it. I just say that if it wasn’t Muhammad there, you wouldn’t feel what you feel when looking at her.

This article was originally published in The New York Times.