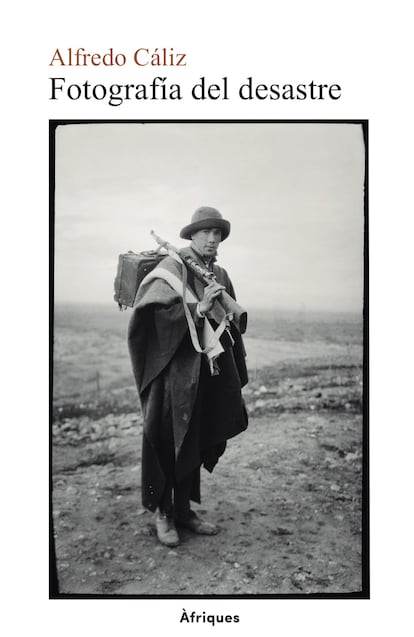

It all starts with a family legend. Grandpa Juan de Dios took Franco to the landing of Alhucemas (September 8, 1925). A young Grenadian, 19, who, pushed by propaganda and patriotic fervor was enlisted in the newly created Spanish legion, loads on his shoulders, then, colonel who will later lead him and will be perpetuated in a dictatorship of 40 years on the other side of the Mediterranean. A story that serves as a thread at (Madrid, 57 years) to dive in relations between Spain and, historical memory or family traumas and countries in their new book (àfriques Edicions, 2025). A work that is difficult to classify within a specific literary genre and that is tasted by the search for forgiveness.

Ask. Countries, like people, have memory?

Answer. Countries are built in relation, or against other countries. From the opposition, from contrasts, the definition of who we are arises. That is, the identity, which seems the most fixed thing in the world, does not arise from the ground, is built in front of the other.

P. The question was if countries have memory.

R. I think so, although memory is fragile, so I would trust history more. And, although sometimes it costs me to see the two words together, historical memory, somehow we have to call that form of restoration of justice towards the parties when there is a trauma.

A part of our history that has been stolen, silenced. It is the passage of the Arab through the Peninsula. I think it has to do with a sin of Islamophobia

P. Do countries also have traumas, then?

R. Of course, the countries accumulate the traumas that do not solve. I think the most recent in Spain is the civil war, which continues with a lot of fringes hanging. They are things that are unsolved, they cannot hide under the carpet, because then they leave.

P. Does your book talk about this?

R. This book also addresses a part of our history that has been stolen, silenced. It is the passage of the Arab through the Peninsula. I think it has to do with a sin of Islamophobia. And we will not complete ourselves, or break the trauma, until we integrate that part of ours that we have lost. I believe that the construction of this traumatized Spain has to do with the construction of a Spain that forgets one of its parts.

P. Is that concretized in the relationship between Spain and Morocco?

R. Of course, there is trauma, because, a country like ours is built based on denial. We have projected our negative image in Morocco. We have denied that relationship, which is very exchange, very fruitful. Perhaps because of that trait, that Islamophobic being, we have built an identity in relation to not being like them. With Morocco there are, first, secular prejudices and then a great historical misunderstanding.

P. In his book he affirms that in the Rif, in the former Spanish protectorate, there is a relationship of love and hate with Spain.

R. The Rife have always been divided, and they are still. They have many cabils that have never been completely united, some in favor of the Spanish presence, others not. Abd el-Krim, which I speak a lot in my book because it is a very important historical figure to understand the RIF, Spain and Morocco, was the first to unify the cabins in an effort against the Spanish occupation and proclaim the Republic of the Rif, just after (July 1921). And the idea of the Republic is still very alive in northern Morocco, because, really, with whom the RIFs feels a deep disaffection is with the Majzén, the state, Moroccan.

P. Is that family legend about his grandfather and the landing of Alhucemas that led him to Morocco, a country that stars in his first photographs book?

R. I went to Morocco in 1992 to work as a photographer’s assistant in a movie called. I was 19 years old. I was starting to take pictures and it was my first contact with the country. I took few personal photos, but they were the typical of any tourist. And in his book South of Tangier: “You are not in Morocco until you stop doing what you are supposed to do.” So I returned later and that was when I got fully. I lost many times because of the Medinas, I got into people’s houses and, following that, I emotionally connected very easily with Morocco. From there leave 10 years of trips that culminate with the publication of my book Inshallah.

P. And then, they began their trips through sub -Saharan Africa.

R. The first time I traveled south of Sahara was in 2000. I had the sensation of epiphany that I was white and they black, that clear from the beginning. The first thing I did was photograph a black photographer. And I have done many more of these characters to give them visibility, to invite people to think that they are the ones who have to tell their stories.

P. What was your first country?

R. Cape Verde. They were trips that P. was commissioned to me what was their first country?

R. Cape Verde. They were trips that Marie Claire’s magazine commissioned Uganda, Senegal, Mali, Nigeria … I had to cover Africa, social issues, and I was happy because I was beginning to travel through those countries, linked to journalism, NGO projects, microcredits to women, issues such as female genital mutilation or AIDS. And, as of 2003, I began to collaborate with the country. I went to Sierra Leone with Juan José Millas and then many more reports for reports such as Lola Huete, Rafa Ruiz, Tomás Bárbulo emerged. Later with the future planet, the possibilities of working in Africa opened much more, of doing journalism.

P. I remember that future planet was inaugurated with an article by José Naranjo and yours on the immigration routes:

R. It was the first report for future planet and let’s say it was the time when I enjoyed traveling with Pepe Naranjo. We both had the same desire to do long things and on four bitches we did the trips, it excited us deeply. In that specific report there were almost three weeks. Then we went to Senegal and did, whatever, a gold mine in Ghana. Perhaps, be a photographer from another era, in which it was intended to spend more time in the places. But that is now done otherwise, the irruption of the networks has remarkably changed the landscape of journalism. Everything is faster, more immediate and above all a lot of African journalists and photographers have been incorporated with a lot of capacity and a strong desire to tell their own history. And that’s good, very good. From the beginning, I at least, I have needed it, break with that divided world between those who look and those who are looking. Division that has coincided with the color of the skin.

A country like ours is built based on denial. We have projected our negative image in Morocco. We have denied that relationship

P. Why was photographer?

R. Because I wanted to go far. I used the photograph to leave home and, as the neighborhood was afraid, I had to go to the world.

P. You wanted to go far because there were problems at home. Your book starts from Annual’s disaster, but, perhaps, the true photograph of the disaster is not that, but that of the relationship with your father. It seems that in the book you want to adjust accounts with yourself and with it.

R. Yes, the two things. With myself and with my father, who left home. And, also, to take away, in some way, that shadow that I describe in the book that my father was, which did not allow me to enjoy the recognition that others gave me, because he had never given it to me. So, forgiving that clean.

P. Another line that travels your book is forgiveness.

R. Of course, forgiveness, obviously, is a nuclear theme of the book. Probably, I was starting to forgive my father. And forgive someone is nothing other than lighten. And I believe that for this there is an exercise to do and that I have tried to do in this book.

P. Returning to the beginning of our conversation, do countries also forgive?

R. Of course, they have to forgive. We speak at the beginning that they have memory, traumas … and therefore, too, they must forgive. Is that forgiveness is fundamental. Forgiving is almost like forgetting. And forgetting is good.

P. And how does a country forgive?

R. Well, I believe that with hygiene in institutions, being able to recognize their mistakes and with a lot of education, that does not indoctrination.

P. And Spain and Morocco, can they forgive?

R. Yes, I think so. Morocco and Spain have been looking for many years.