Israel remains invested in overthrowing the Ayatollas regime, although this is not an operational goal, but a long -term strategy. Donald Trump even put this hypothesis, but shortly thereafter assured him that knocking him down would only bring “chaos.” Iranian politics experts explain why ending theocracy in Tehorão is extremely difficult, because it should be cautious in comparisons with previous external interventions, such as Iraq, and what can happen if the Iranian regime, in fact, collapses

It remains “realistic” that Israel’s war against Iran may lead to a change of regime in the country, almost half a century after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. At the end of 12 days of continuous attacks on Nuclear, military and economic infrastructures of Tehran, it seems to be one of Telavive’s goals, even not immediate. However, doubts remain about to what extent the United States are aligned with Israel at this point.

In the aftermath of the first US attacks on Iran last weekend, against three nuclear centers, the US state and defense departments were quick to clarify that the intervention was limited and that it did not mean that Washington was actively involved in the war, much less that he wanted to cause a change in the leadership of Iran. Hours later, the US president himself took a contradictory position, writing on his social network: “It is not politically correct to use the term ‘regime change’, but if the current Iranian regime is unable to do the big will again, because there would be no change of regime ??

Already after the adaptation of his campaign slogan and presidency to Iranian reality–and reacting, furiously, to break a ceasefire between Israel and will announce hours earlier, Donald Trump seemed to turn back. “The US does not want a change of regime,” he said to journalists before embarking on the NATO summit in The Hague. “A change of regime only brings chaos.”

With all advances and setbacks, the hypothesis remains “definitely realistic,” CNN Portugal Houssein Al-Malla, from the German Institute of Global and Regional Studies (Giga), because “history shows us that the collapse of regimes in the Middle East is never out of the question-see the case of Libya in 2011 or Iraq in 2003”. Still, it assumes the specialist in international interventions in fragile contexts, a big issue hangs in the air: “Not only is forced regime change extremely difficult to control, but also often creates more instability than the one that resolves.”

After announcing a ceasefire and the end of what he himself called the “12-day war”, the president of the United States spent the dawn from Monday to Tuesday agreed to see what they did not want: Israel and will violate this same ceasefire Photo: Evan Vucci/AP

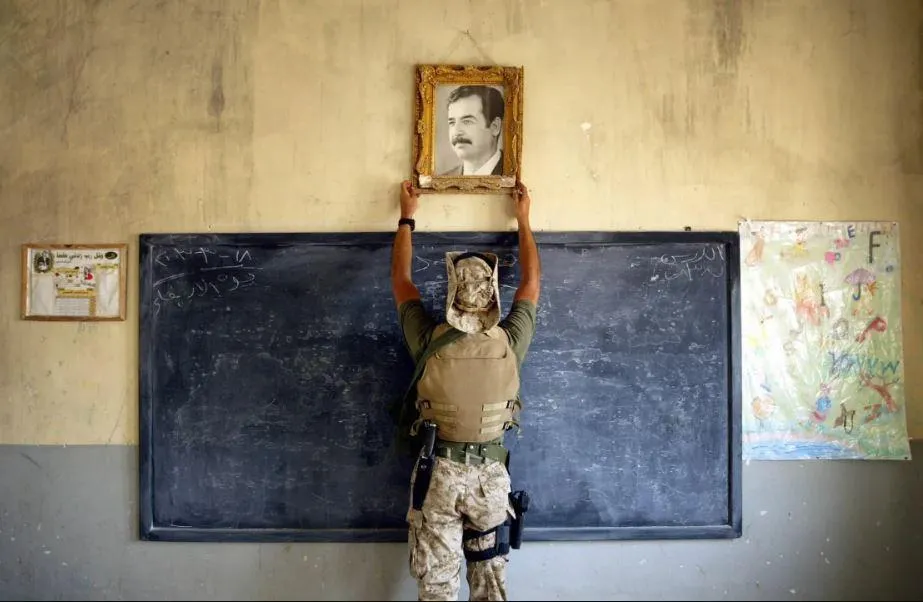

Iraq is a good case of study in the context of the country’s invasion across 2003 after Benjamin Netanyahu ensured Western allies that the Saddam Hussein regime was making weapons of mass destruction. It is known today, almost 20 years later and after a long war that caused thousands of civil and military deaths on both sides, that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, a version that the Israeli Prime Minister kept last week, although in 2022 he had assured the US Congress that “there was no question that Hussein was developing” this armament.

At the turn of the millennium, Netanyahu assured the US that testifying the dictatorship of Saddam would bring stability to the country and the entire region, and was also based on this argument that George W. Bush’s administration opted for direct intervention. Now, and in the face of news that before the beginning of this conflict, the parallels with Iraq abound, although the Iranian case is different from, two other countries that have seen regime changes in the sequence of interventions led by the Americans since the Millennium turn.

“As we have seen, reality changes every hour, but I think it is important to highlight the differences between conflict in Iran and these cases,” says Jonathan Monten, director of the University College London (UCL) international public policy program. “In Iraq and Afghanistan, the US had local partners on the ground, the resistance was well organized and there were already relatively strong rebel groups within the US -backed countries, including even in the case of Libya, where US air attacks were accompanied by support for local militias.”

On the contrary, he points out the British analyst, “there seems to be no such group in Iran at this time – no local partner or plausible group that could seize power if the US or Israel dropped the current regime.”

“Iran is not simply another authoritarian state, it is a theocratic republic with a deeply institutionalized governance system that combines clerical authority with elected positions,” adds Al-Malla. “This double structure makes the Islamic Republic fundamentally different from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which was a single -leading autocratic regime and a coercive security apparatus.”

“The supreme leader is not just a political figure, but a religious authority,” says Houssein al-Malla, and this fact complicates not only external intervention as internal dissent, but was seen with the repression of the thousands who mobilized against the oppressive regime after the death of Mahsa Amini, in 2022 Photo: Bulent Kilic/AFP via Getty Images

Among the United States, attacking the three largest nuclear centers of Iran on Saturday night and Trump announced a fragile truce between Teerão and Telavive – which were accused by part of part and new Israeli attacks on Iranian territory – the whereabouts of Aiatola Ali Khamenei.

Hidden in a bunker, he reported the newspaper, Iran’s supreme leader renounced all electronic communications, transmitting information through a faithful counselor, and has appointed three potential successors to take his place if something happens to him. “Since there is no local resistance, if the US or Israel try to murder the Supreme Leader, it will most likely be replaced within the current regime, and that is the big difference from previous situations where the US has overthrown regimes,” explains Jonathan Monten. “In the case of Iran, the leadership would be replaced internally – and the new leadership would be in arms with the same strategic issue that the current leader faces.”

Distinguishing Iran from Iraq, Afghanistan, and even Libya is what Houssein Al-Malla defines as the “institutional architecture” of the Iranian Shiite regime. “Religion plays a central role in defining the internal legitimacy of Iran and its stance on foreign policy,” says the analyst based in Hamburg. “The supreme leader is not only a political figure, but a religious authority, which complicates both internal dissent and external intervention. A challenge to the regime can easily be framed as a challenge to Islam itself, particularly between its loyal base – and this ideological layer creates a resistance that is simultaneously doctrinal and strategic, the way religion is inserted in a wide more institutional architecture and makes the regime more difficult to dismantle and more capable of absorbing the shocks. ”

In addition, when Iran faces threats, the tendency is for elites in the power centers, from the supreme leader to the presidency and the parliament, through the powerful body of guards of the Islamic Revolution (IRGC) and the judicial power, unite to face them. “These institutions are not always in agreement and competition between the elites is a permanent feature of Iranian politics-but when the country is under external threat, there is a historical tendency for these actors to close ranks,” explains Al-Malla, who gives war-branches as examples (1980-88), the “maximum pressure campaign” of the two Trump administrations and the conflict now on an ongoing conflict with Israel.

“All these experiences have triggered similar patterns of elite consolidation. Even the reformist voices that criticize internal regime policies often change to a nationalist position when it is considered that sovereignty is under threat. And in this sense, the pressure from abroad can, paradoxically, reinforce the regime from the inside – reinforces the argument that the Islamic Republic is not a target by its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but its actions, but Identity, which, in turn, justifies internal control. ”

The signs that have come from Iran in the last 14 days point to this resilience of the regime. As Mohammad Ali Abtahi, reformist politician and former vice president of Iran, says: “[A guerra] softened the divisions we had, want among us [pilares institucionais]whether with the general public. ”

“The collapse of the Baath regime in Iraq has opened the door to sectarian conflicts and foreign intervention and Iran may have a similar destination if the transition is conducted from abroad” Photo: Chris Hondros/Getty Images

With the reality changing hourly, and Trump visibly annoyed by Iran and, in particular, with Israel for disrespecting their ceasefire, doubts about whether a change of forced regime continues on the horizon. For UCL’s Jonathan Monten, “after US bombing, Israel has reached its most significant military goals and seems unlikely to continue to try to change the regime without US support – but you need to see what happens in the coming days.”

As ABTAHI indicated to the New York Diary over the weekend, Israel miscarred the Iranian reaction to the war. And as Houssein Al-Malla indicates to CNN Portugal, “the change of regime in Iran is still a long-term strategic aspiration” to Israel-which seeing the leadership of the Archirrival as “the main factor of regional threats”, considers this change of regime “the only way to ensure lasting security” in the region. Still, he opposes the expert, “even in Israelite discourse this is more of the ultimate goal than an immediate operational objective.”

In the US, the case is quite different and requires caution. “Although some voices still defend the change of regime, current policy focuses more on containment and deterrent than in intervention,” says Al-Malla, because “the costs and consequences of previous regime change efforts remain well present in the minds of the decision makers.”

Although at this stage, the change of regime is not an actively persecuted policy, the hypothesis should not be discarded, especially if the conflict between Israel and will last in time. As the Giga expert assumes, “a prolonged conflict can create cracks.” An example of this is the fall of the Shah in 1979, following several years of growing dissent and foreign involvement. ”

From Paris, Reza Pahlavi, heir to the deposed Shah, asked at the beginning of the week to “all those who are loyal to the Iranian nation and not to the Islamic Republic” to take advantage of the current conflict to rise against Aiatolas Theocracy, ensuring that they do not want power to themselves, but offering to lead “a democratic transition” in the country. It is true that his father’s deposition has been a strong memory that apparently stable regimes can be rapidly undone, “there are serious chances that his request falls apart, says Houssein Al-Malla. “There are exiled monarchical groups and diaspora opposition networks trying to revive this dynamic, but they lack coherence and internal legitimacy.”

If the current conflict drags on, and the regime change even happens, “it will not be simple, previously accompanied by chaos, internal struggles and risks of a vacuum of power,” says the expert. “The collapse of the Baath regime in Iraq has opened the door to sectarian conflicts and foreign intervention and Iran may have a similar destination if the transition is conducted from abroad. The change of regime in Iran is possible, but it is not a line of arrival. It is a rust – and if we turn it on without a plan, we risk triggering a regional fire storm.”