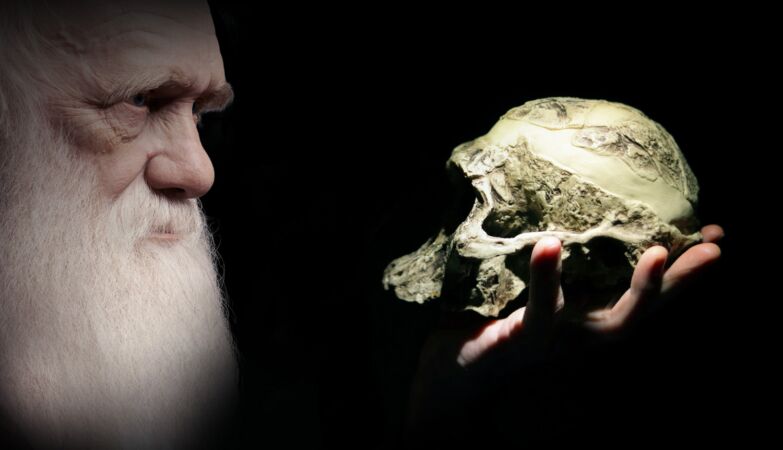

ZAP // Fabio Paiva; IvanM77 / Depositphotos

Human evolution may have given us larger brains-with an unexpected cost: that of having made us more vulnerable to cancer, reveals a new study.

One small genetic change That helped give humans their great brains may have become more susceptible to cancer than our closest primates relatives reveals a new UC Davis Comprahensive Cancer Center investigation.

O, published this week in Nature Communicationsreveals as a single amino acid replacement in an immune protein called Fas Ligand It makes human cells to combat cancer less effective against solid tumors compared to chimpanzees and other nonhuman primates.

The authors of the study found that humans have a unique mutation, in which the amino acid Serine replaces proline In position 153 of the protein fas ligand.

This change apparently minimal makes protein vulnerable to being deactivated by plasminaan enzyme that tumors use to spread throughout the body.

“Evolutionary mutation in FASL may have contributed to the larger brain size in humans,” he says Jogender zip-singProfessor of Medical Microbiology and Immunology and Senior Author of the study, quoted by.

“But in the context of cancer, It was an unfavorable commitment because the mutation gives certain tumors a way to disarm parts of our immune system, ”adds the investigator

The investigation suggests that this genetic change helped neural development during human evolution, but came with an unexpected cost: Greater vulnerability to cancer in modern humans.

How tumors exploit this weakness

FAS Ligand serves as a crucial weapon for immunity cellstriggering the programmed cell death in cancer cells through a process called apoptosis. However, the human version of this protein contains a structural weakness that aggressive tumors can explore.

In cancers like the Triple-negative breast cancercolon cancer and ovary cancer, high levels of the enzyme plasmin can neutralize The Human Ligand before it kills the tumor cells.

This mechanism helps to explain Why certain immunotherapies work well Against blood cancers, but often have difficulties with solid tumors.

Researchers have found that the FAS Ligand Humana is highly susceptible to plasmin cleavage, while the versions of chimpanzee and monkey Rhesus resist this degradation.

In addition, they concluded that tumors with high levels of plasmin show greater resistance to treatment – and that Blocking plasmin can restore power to kill cancer of human immunity cells

The discovery offers new strategies to improve cancer treatment. By combining current immunotherapies with specially designed plasmin inhibitors or antibodies that protect the Ligand FAS, researchers can be able to improve immunity responses against solid tumors.

Ovary cancer cell tests derived from patients confirmed that tumors with high plasmin activity were significantly less sensitive to the Human Ligand compared to the primate versions. Block Plasmin Activity restored the effectiveness of immunity cells that kill the cancer.

“Humans have a significantly higher cancer rate than chimpanzees and other primates, ”said Tushir-Singh.” There are many things we don’t know yet and we can learn from primates to apply to improvements in human cancer immunotherapies. “

The brain connection

O evolutionary context Add another layer to this discovery. Human brains are approximately three times larger that chimpanzee brains, requiring careful regulation of cell death during development.

The same mutation that has made FAS ligand vulnerable to plasmin can have Provided advantages during neural developmentby reducing premature cell death on brain tissue.

This represents a classic evolutionary commitmentwhere beneficial genetic changes to a characteristic carry hidden costs in other places.

Similar patterns were observed with other cancer -related genes such as P53 EO BRCA2where variations that provide advantages in some contexts increase susceptibility to the disease in others.

The investigation team demonstrated that antibodies directed to specific regions of FAS Ligand can Protect it from degradation by plasmin without interfering with your function of killing cancer.

In mouse studies, these protective antibodies successfully restored the effectiveness of plasmin -rich immunity cells.

The findings suggest that Measure plasmin levels in tumors could help predict which patients could benefit of combined therapies directed to both immune control points and plasmin system.

“This is an important step in customizing and improving immunotherapy for positive plasmin cancers that have been hard to treat,” Tushir-Singh concludes.