About 225 km above France, American astronauts opened the hatch of a spacecraft and found themselves face to face with cosmonauts of the Soviet Union.

“Happy to see him,” said Colonel Alexei Leonov in an accent with a brigade general Thomas Stafford from NASA.

“Ah, Hello, very happy to see him,” Stafford replied to his own accent Russian.

The two men then squeezed their hands.

Today, Russian and American astronauts routinely share trips to the International Space Station, regardless of the geopolitical conflict that divides their nations. But in the summer of 1975, seeing two rival men men greeting in orbit, through a bridge among their coupled spacecraft, was a powerful and unprecedented gesture, witnessed by millions in the world that spinned below.

Hand tightening, which took place 50 years ago, on July 17, defined the Apollo-Soyuz test project, the first international human space flight. This simple partnership symbol between bitter competitors remains a lasting legacy of the mission.

Continues after advertising

“It’s amazing to think that two diametrically opposite countries, with different systems and cultures, essentially ready to destroy themselves, can somehow cooperate and perform this highly technical and complicated mission,” said Asif Siddiqi, a history professor at Fordham University and expert in Russian space history.

A generation after the squeeze of orbital hand, Soviets and the United States would come together to build the ISS. The aged space station has its days numbered, and there are no immediate plans for Russia and US to maintain their cooperation on human space flights. The US also competing with China for dominance in space. But experts like Siddiqi see reasons for hope on the 50th anniversary of the Apollo-Soyuz Mission.

“Whenever they tell me it would never happen today, I think, well, that’s what people said in the late 60’s,” said Siddiqi.

Continues after advertising

“Androgynous” coupling

At the beginning of the space era, while the US ran to reach the Soviet Union, a partnership in space was proposed. In September 1963, speaking at the UN General Assembly two months before his murder, President John F. Kennedy suggested a joint mission to the moon.

“Why, then, should man’s first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition?” asked. “We should certainly explore if scientists and astronauts from our two countries – and around the world – cannot work together in conquering space.”

This dream was postponed, and the US would surpass the Soviets in the lunar race with Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

Continues after advertising

Interestingly, the American arrival on the moon may have created a new window for cooperation. Public support for Apollo missions fell, and the program ended after the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. This left the US space program without an immediate goal.

At the same time, the reputation of both nations was stained abroad: the Soviet Union for the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the US for involvement in the Vietnam War. This has created an additional motivation to jointly reaffirm the status of each country at the top of the global hierarchy.

“They needed to rise and cooperate to show the rest of the world: we are as super and grandiose as we have always been. We are doing things that no other country can do in similar capacity,” said Olga Krasnyak, an associated international relations professor at the National University of Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

Continues after advertising

This mutually recognized opportunity for prestige led to initial conversations among countries’ officers in 1970. From the beginning, it is clear that the mission would face huge diplomatic, technical and cultural obstacles. There was no easy way for launch.

“How do we communicate with people who speak totally different languages and think differently about engineering and problem solving?” Said Brian C. Odom, NASA’s chief historian. “On paper, it seems easy. You throw, we launched, we find ourselves, squeeze our hands, follow our ways. But making it happen without five people die in orbit, it’s incredibly difficult.”

Both sides suspected the safety of the other’s main spacecraft. The three astronauts selected for Apollo 1 died in a fire during a rehearsal in 1967, while the three Soyuz 11 cosmonauts died in space in 1971 when the cabin decreased. Provocations about the superiority of the spacecraft on the other on the other irritated those involved in the mission. American astronauts were used to a much more manual orientation system with Apollo, while Soyuz was largely automatic and controlled from the ground.

The vehicles even used different atmospheres in their interiors. Soyuz simulated the family’s family conditions, with a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen and pressure equivalent to sea level. Apollo, in contrast, used a pure oxygen atmosphere at much lower pressure.

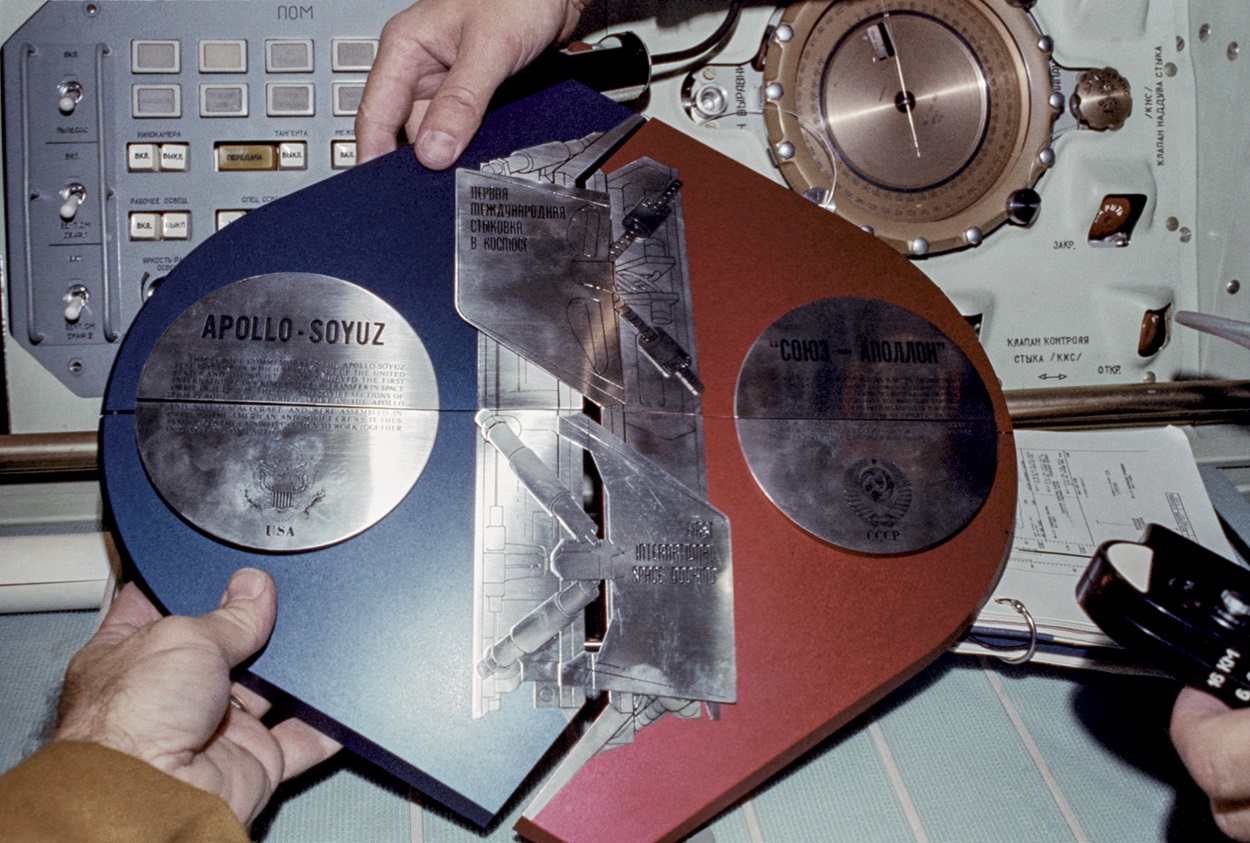

This discrepancy was resolved with the development of a coupling module with hermetic hackles at each end. Once the module connected the two ships, members of the crew of one could enter, ensuring that both the hatches were closed as the pressure adjusted to match the conditions on the other side. When this process was completed, the hatch to the other ship could be opened, allowing the crew to safely enter without risk of “decompression disease,” a condition caused by rapid depressurization.

For this mission, Soyuz was kept at lower pressure than normal to facilitate transitions between ships. The coupling module was also designed to be androgynous, to ensure that no spacecraft was perceived as “feminine” or passive.

While mission planners faced these challenges, a deep and lasting friendship flourished between astronauts and cosmonauts. The Apollo side, led by Stafford, also included Donald “Deke” Slayton and Vance Brand. Leonov flew on the Soyuz side with Valery Kubasov.

The crews learned each other’s languages, although Leonov played that Stafford’s dragged pronunciation was “Oklahomski.” They trained together at NASA’s Johnson space center in Houston and Star City, the Russian space center near Moscow. During these meetings, space travelers hunted, drank and celebrated together. They shared steam baths and participated in snowball battles.

The two commanders remained particularly close to the rest of their lives: Leonov helped Stafford adopt two children from Russia, and Stafford has made a funeral compliment in Russian (or, better, Oklahomski) at Leonov funeral in 2019.

Strawberry and Borscht Juice

Against all the odds, the crews finally reached their launch platforms in the summer of 1975. On July 15, the Soyuz crew took off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, followed by the Apollo crew, which launched about seven hours after the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The approach to the coupling was relatively quiet, although Apollo’s crew found that a “Florida super mosquito” had embarked with them, and Stafford joked that a juice spill had turned Apollo into a “strawberry spacecraft.”

The spacecraft successfully coupled at 12:12, US East time on July 17, high over the Atlantic Ocean. Hours later, the historic handshake was broadcast live to millions of viewers. The mission even inspired a cocktail called Link Up, with equal parts of Southern Comfort and Vodka mixed with lemon and ice, served at the Savoy hotel in London.

The crew spent the next two days exchanging gifts, having dinner together (including gifts with Borscht), listening to music and experimenting. The ships separated on July 19.

“A little messy”

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Americans and Russians again united forces in space, first at the MIR space station in the early 1990s. The American-Russian partnership is now the dorsal spine of ISS, which has been continually inhabited since 2000.

This season is in its final years. Russia argues to build its own separate successor space station, and the US is fostering commercial orbit stations-efforts that can make Apollo-Soyuz seem like a distant memory.

But Krasnyak, the Russian expert in international relations, said the legacy of this mission, and cooperative spatial exploration in general, remains important for the Russians 50 years later. Whether the US and Russia partner in future human space flights or not, she noted that the two powers remain world leaders shaping international deliberations about the space.

Siddiqi, the historian of the Russian space flight, sees the US Mission of 1975 as a precursor to the complex international partnerships that characterize the modern space flight, even of an “indirect way.”

“It was a little messy, but the way takes back to Apollo-Soyuz,” he said. “Other historians would see this differently, such as a break or an isolated event, but I see a lot of continuities.”

Odom, NASA’s chief historian, does not see Apollo-Soyuz as a direct parent from ISS, or other subsequent spatial collaborations. From his perspective, the legacy of the mission is more in the context of a time when two conflict powers extended an olive branch in orbit, with repercussions on how their citizens were on Earth.

“The people involved are thinking about what cooperation can really mean,” said Odom. “If we can cooperate with the Soviet Union in this way, we can cooperate with anyone.”

c.2025 The New York Times Company