Brazil’s defeat to Uruguay in the decisive game of the 1950 World Cup, now known as Maracanazo, was called by Nelson Rodrigues “Our Hiroshima”. “It was a national humiliation that nothing, absolutely nothing, can heal,” wrote the chronicler in the sportsman, eight years after the match.

Nothing, in fact, healed. Not five world championships. The maximum that occurred was the replacement of that 2 to 1 with a 7-1, which passed in the past decade to be the symbol of “national humiliation”, to the point of making “7 to 1” a popular expression that denotes resounding failure.

But the 7-1 defeat to Germany in the 2014 World Cup semifinals, held in Brazil, has a different weight from the 2-1 defeat to Uruguay in the final duel of the 1950 World Cup, held in Brazil. 75 years ago, there was almost certainty of triumph.

“It was a new age that was going to open to Brazilian football. Everyone was waiting for her: she was scheduled to start. July 16, 50,” Mario Filho wrote in the famous “The Black in Brazilian Football.” “What doubt could there be? Flame factories tried to make hundreds of thousands of flames: ‘Brazil, world champion’.”

Brazil was not world champion.

It was enough for the tie with Uruguay, after thrashed over Sweden and Spain in the final quadrangle. The expectation was a new defeat, but the crowd present at the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Stadium – after baptized in honor of Mario Filho and known by the name of the Rio de Janeiro neighborhood of Maracanã – saw a heinous turn.

“For we entered a stunning barrel in the beards of 200,000 Brazilians. It was a worse tragedy than that of Canudos,” wrote Nelson Rodrigues – Mario’s Brother – who, with his playwright, visualized a scene of “national suicide”. “We were, all of us, a nation that almost takes anthill.”

More than the goals of Juan Schiaffino and Alcides Ghiggia, he has echoed for seven decades and a half decades the slap of Obdulio Varela. A slap that, it seems, never happened.

It was for history that the Uruguayan captain assaulted the Brazilian Defender Mustache. The person responsible for reporting the probably fictitious episode was Mario Filho, who made considerable concessions to the imagination and had no images to deny him.

There is no complete record of the video match. The moves of the goals, one or another unimportant move and scenes of joy and sadness left in the world that was the largest stadium in the world. The supposed aggression was really on the role, in Mario’s texts, but gained the popular imagination and was pointed out as an explanation for zebra.

Brazil had done 7-1 in Sweden and 6-1 in Spain, with the crowded audience singing the song “Bullfights in Madrid”. Uruguay had suffered to seek a 2-2 draw with Spain and defeated Sweden 3-2. It was evident the favoritism of the home owners, and such a surprising defeat had justifications that went beyond tactical and technical concepts.

In short, the obdulio slap cowered Brazil and magnified Uruguay.

It matters little that Mario Filho himself has reviewed his initial version. In the latest edition of “The Black in Brazilian Football”, he wrote that Varela “grabbed the mustache by the neck”. “He didn’t put his hand on his face. Either way, the core of the issue has not changed.

The episode helped Nelson Rodrigues develop the concept of the “mutt complex”, the “inferiority in which the Brazilian voluntarily puts himself in the face of the rest of the world.” According to him, “Obdulio treated us the kicks, as if mutts were.”

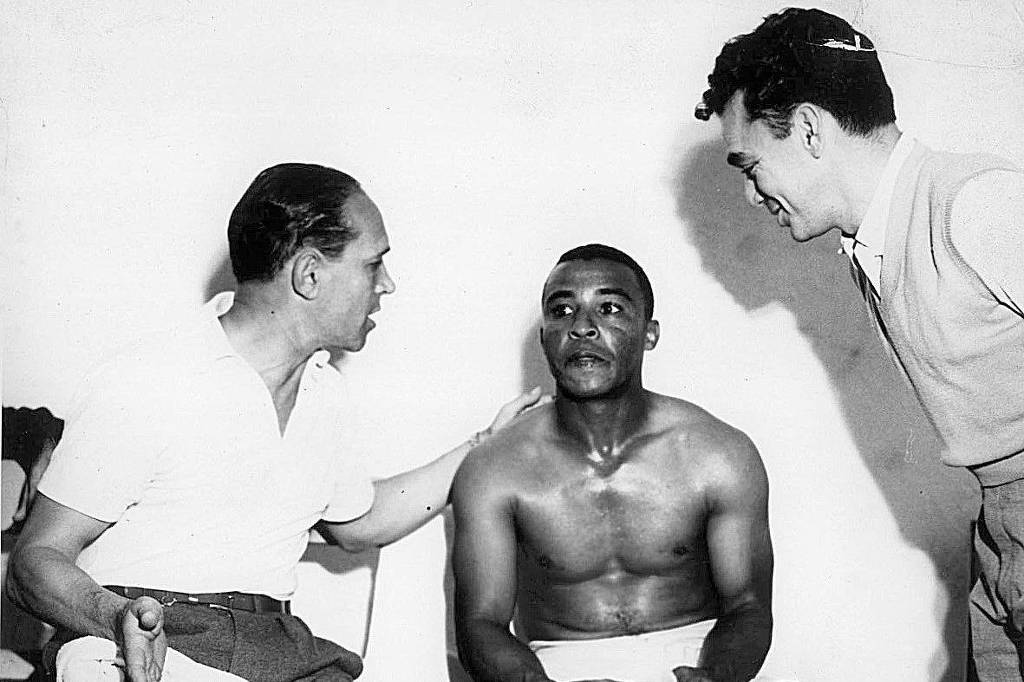

Treated the kick -or tapas, or numbers, depending on the account – mustache was pointed out as one of the culprits. He was a black man, such as goalkeeper Barbosa and defender Juvenal, also responsible for failure. “It was what it gave, according to the racists who appeared to the hills, to put more mulatto and black than white in the Brazilian writer,” wrote Mario Filho.

No one suffered as much as Barbosa, who failed Ghiggia’s fatal kick. In 2000, shortly before he died, he noted that his punishment may be excessive. “What is the maximum penalty in Brazil? The maximum penalty for a crime in Brazil is 30 years. I pay for that goal for 50,” he said.

Barbosa is a historic idol of Vasco, an exceptional quality archer. It is, however, more remembered by the ball that did not take than the many that grasped. His trajectory – specially his pain – caused and caused attraction, with multiple representations in the field of arts.

One of them is Raul Drewnick’s book “The Ghost Goalkeeper”, a simple children’s work that rehabilitates the figure of the player. The work is “dedicated to the memory and honor of Barbosa, goalkeeper of Brazil at the 1950 World Cup and supreme martyr of Brazilian football”.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the victim, never for the tyrant. Barbosa was, yes, the biggest victim of the biggest tragedy of Brazilian football, a Greek drama passed in Maracanã,” Drewnick told Sheet.

“Everyone got rid of the blame on Barbosa, that was the drama. It was easy to get such an obvious victim, the goalkeeper who took two goals. Who speaks today of Flávio Costa?” Asked the writer, Corinthian, still annoyed because the right-wing Cláudio, the largest top scorer in Corinthians history, was not summoned.

Really, few remember Flávio Costa. Remember Barbosa’s error. And they remember the Obdulio slap, even if it has not happened.