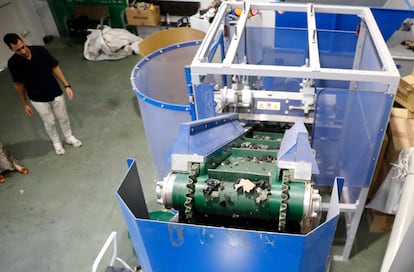

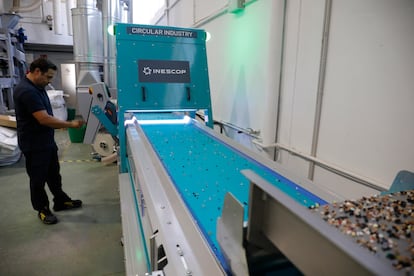

A bucket in the form of inverted trapeze, a transmission tape, a crusher and several tubes for the channeling and separation of different materials. This plant laboratory plant, which fits in a small industrial ship, is the only one that exists in Spain aimed at, for the moment, the investigation of the difficult shoe recycling process. It is located at the headquarters of the Inecop Footwear Innovation and Technology Center, in the Alicante municipality of Elda, one of the nerve points of the sector in the province, together with Elche.

“Footwear is a challenge for chemicals, engineers and biologists,” says Borja Mateu, innovation agent of the center. “If it costs us to recycle a plastic container, which is hardly formed by one or two components, it is easy to imagine how complicated a shoe is, which has a twenty one, between tissues, metals, polymers or adhesives,” he adds.

There is no “specific container for the collection and separation” of this product, laments Mateu. And the legislation, with a royal decree to regulate the circular economy of footwear on the 2026 horizon, begins to create an emergency situation.

The data handled by the Eldense Research Institute, 2023, reflect that Spain is the twenty -world shoes producer, with 80 million pairs that leave the factories. In addition, the industry imports 315 million more pairs and exports 156. In terms of consumption, “we go out to 4.4 pairs per head per year and more than 95% ends up in landfills, incinerated and without management,” says the Alicante scientist. At an average weight of 600 grams per par, the sum is approaching the 130,000 tons of potential waste every season. And with hardly any way out in the growing second -hand market.

“The shoe does not come in the textile” in the reuse business, Mateu explains. “It deforms with its first use to adapt to the foot, it affects the health of the user if it is not used well and is difficult to hygienize, since it is not washed in the same way as the clothes.” There are also no plants that separate it, except for a pilot project in Tenerife. “In Europe, there are only some that have started operating in France, the Netherlands and Italy. If you throw a shoe to the container, it ends in the garbage,” he says.

The Inescop plant was inaugurated in 2022, although in reality it began to operate in 2019. Elche The Eldense center maintains agreements with NGOs and social entities, which are discarded. Once there, the processing plant faces the problem of separating elements “that are not even seen, such as the Cambrillón, which is a metal guide that is inserted in the sole.” But a shoe, a boot or heels can be formed by “leather, polymers, rubbers, synthetic materials, textile fibers, metals such as iron, aluminum or zamak- a alloy of zinc, aluminum, magnesium and copper- and adhesives that, by definition, are complicated from separating,” says the specialist.

Inescop tests consist of crushing footwear and separating, with different processes, ferrous materials and resulting particles depending on their size. They also divide and distribute density materials, with light textiles on the one hand and the sole, leather and foam components on the other. In their laboratories they do not stay there. “Chemical recycling is the future because it allows the material to make the industry pure or other sectors, but it must enter clean, without impurities, to be able to perform the dereticulation of the Eva rubber, the lock of rubber or the biodegradation and composting of the leather.”

In addition, “we transmit to the manufacturers guidelines for the use of recycled and recyclable material. In a practical way, in addition, attending to the production processes, which understand it as another factor and not only attend at the price, fashion material or color. It is the ideal path. The only one, actually.” Because even seemingly simple rubber flukchs and PVCs can be a challenge for recycling. “If we apply the processes for the refor of rubber, the PVC burns,” he says. However, this awareness is not simple either. “The footwear is an industry industry,” says Mateu, “is based on small factories that specialize in certain components and then the big ones join and get for sale.” “In those SMEs, which already live in an unstable situation, it is very difficult to make them see the need for recycling, but we are approaching.”

With the impulse of the European Union to the circular economy, all sectors are committed to recycle. And that is where the collective systems of expanded responsibility of the producer (SCRAP) enter, which manage the recycling of waste from the different industries. At the beginning of this month of July, the Ministry of Ecological Transition brought to Public Exhibition the Royal Decree that will regulate the SCRAP of the fashion and footwear sector, and that it is expected that it enters into force with the arrival of 2026.

In Spain, for now, there are two, in almost larval state. Re-Veso, which covers both fields. And gerescal, exclusive to footwear, formed by nine large companies from all over Spain and whose executive director is Rafa Reolid, who insists that “the footwear cannot be put in the same bag as the textile.” “Our function is to give solutions to manufacturers and distributors to recycle shoes,”

They have already established “agreements with NGOs such as Caritas or Human and with clean points of different waste consortia”, for selective collection. Reolid admits that it is still “statements of intentions that will be strengthened when regulatory regulations.” “NGOs usually have second -hand stores, but what they don’t sell,” he says. “Now, we will buy them and take them to recycle.” The fate of used shoes will be “first, the second hand.” “Then, energy regeneration, that is, allocate it to the food of boilers in industries such as cement, for example.” “The third way would be pirolization,” that is, the decomposition of footwear in different materials, “such as the sole or oils, which can be used in the petrochemical industry.” And finally, in the smallest part, it is expected to go to the recycling process that Inescop is testing “with a machine that would have to industrialize.” At the moment, a greater proportion of recycling with current knowledge cannot be reached.

Although the ideal would be to use these shoes waste in the manufacture of other shoes, and there are projects to reuse the sole material in the manufacture of other soles, this is also very complex today. “The shoe residue does not have to return to the footwear,” says Reolic, “it is easier for the furniture to go, for example.”

There are already signatures that revive them as decorative and exhibition material in their stores, they say in Inescop, where crushed pieces also apply in the elaboration of urban banks, soils for children’s parks and climbing and even “asphalt for filming traffic”.