Kikuyo Nakamura and Mitsuko Yoshimura know they don’t have much more life. But this gives them greater urgency to educate younger generations about the costs of a nuclear war

When Kikuyo Nakamura’s adult son discovered lumps on his back, she assumed that they were only rashes.

Still, he encouraged him to go to the hospital-better to prevent remedy.

Hiroshi, his second child, was born in 1948, three years after the US released an atomic bomb in Nagasaki. As a survivor of bombing, Nakamura feared long ago that he could convey health problems to his children.

In 2003, at the age of 55, Hiroshi went to the hospital. They spent two days without any news. Then three. Then a week.

Finally, Nakamura went to the hospital, where her son told him “they will do more exams,” he says to CNN.

Kikuyo Nakamura, now 101, believes he passed cancer to his son, after a doctor suggested that radiation passed through breast milk Photo: Futa Harm, Cnn

The results showed that he had stage 4 leukemia – an advanced blood cancer that had already spread to other parts of the body. According to Nakamura, the doctor told her that she had passed cancer to her son-suggesting that the radiation that caused cancer was transmitted by breastfeeding when he was a baby.

When Hiroshi died six months later, his mother believed he had killed him. It is a thought that still haunts it, more than two decades later.

“I was taken by guilt and suffering … Even now, I still believe in what the doctor said, that I caused the cancer,” Nakamura shared, now 101. “This guilt still lives on me.”

Kikuyo’s son, Hiroshi, was born three years after the US released an atomic bomb against Nagasaki foto: FNN/Cortesia of Kikuyy Nakamura

Women who are exposed to nuclear radiation are generally encouraged to interrupt breastfeeding immediately after an atomic explosion. But experts claim that there is no concrete evidence that the “Hibakusha” of the first generation – survivors of the atomic bomb of World War II – can transmit cancer material to their children, years after the exhibition.

The week of the 80th anniversary of the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, elderly survivors – some, such as Nakamura, over 100 years old – share their stories of suffering and resilience while they can still.

Many of the survivors were young women, pregnant or fertile age, when bombs fell and lived much of their lives under a strong shadow of fear and stigma.

Doctors, neighbors and even friends and family told them that their exposure to nuclear radiation could lead them to have children with disease or disabilities-this could even conceive.

Hibakusha women – the Japanese word for atomic bomb survivors – faced a severe stigma, often guilty of infertility or not related to radiation Photo: US Army/Courtesy of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Even when a child’s infertility or deficiency had nothing to do with radiation exposure, Hibakusha women often felt guilty and rejected.

Those with visible scars of the explosions faced barriers to the wedding. Physical wounds were harder to hide – and clearer proof of exposure.

And at a time of society when the value of women was closely linked to marriage and motherhood, this stigma was particularly pernicious.

This has caused a large number of surviving women-many of whom suffered from TSPT (post-traumatic stress disorder)-“hiding the fact that they were Hibakusha,” according to Masahiro Nakashima, professor of radiation studies at Nagasaki University.

“In a society like the Japanese – where gender discrimination and male domination are deeply rooted – women have been especially affected by radiation,” Nakashima tells CNN.

Nagasaki’s bomb had a lasting impact on women hit by the explosion

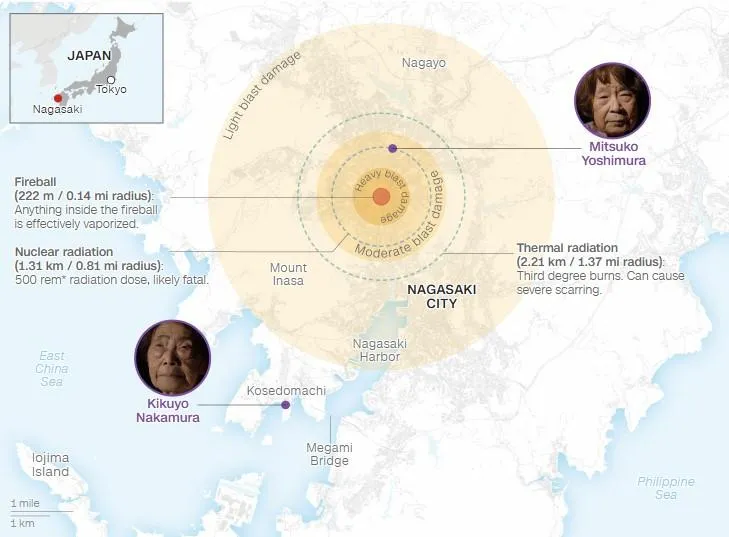

All survivors of atomic bombs in Japan received government identity cards. Mitsuko Yoshimura worked at the Mitsubishi Arms factory in Nagasaki when the bomb detonated, 1.1 km away, according to his ID card. Kikuyo Nakamura was about 5 to 6 km from the place where the bomb fell outside the city.

Atomic pump effect distances in Nagasaki on August 9, 1945

* Radiation is measured in REM’s. It is expected to dose of 500 REM kill half of the people exposed within a month.

Sources :, Futa Nagao (photos)

Graph: Soph Warnes, CNN

Wounds for Life

Exposure to radiation affected some survivors of the second generation, depending on the moment of pregnancy.

The embryonic period – usually between the 5th and the 15th week – is especially sensitive to the development of the brain and the organs of the fetus. Women exposed to radiation during this period showed a higher risk of giving birth to children with intellectual disabilities, neurological problems and microcephaly, a condition characterized by small head and impairment of brain function, according to the Japan-Eua Radiation Research Foundation (RERF)-successor of the atomic pump victims committee, formed shortly after World War II.

Other studies show that Hibakusha women also faced long -term health risks.

A 2012 RERF study found that. Solid cancer rates in women at 70 increased 58% for each gray of radiation absorbed by their bodies at age 30. A Gray is a unit that measures the amount of radiation energy that a body or object absorbs. For men, solid cancer rates increased 35%.

For hibakusha women, stigma was particularly cruel in a society that connects its value directly to marriage and motherhood Photo: US Army/Courtesy of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Nakamura was 21 years old and hung clothes outside the window around 11am when the bomb fell to Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. He says he was 5 kilometers from the epicenter – just beyond what experts call.

The young mother saw a bright light, followed by a crash and a strong gust of wind that cast her into the air. When he recovered his conscience, his house was destroyed – furniture scattered everywhere and glass shards covered the floor. Nakamura called her own mother, who helped her take care of her eldest son.

Relieved that they were not physically injured, the family fled to an anti -aircraft shelter. Only the next day Nakamura realized the dimension of destruction. Relatives who lived near the University of Nagasaki, closer to the explosion, died.

Nakamura claims that she has not suffered any effect on radiation exposure. Four years later, they removed his womb, and at age 70 the doctors found a tumor in their abdomen, but doctors told him that none of the problems were related to bombing, he says.

Psychological trauma, however, has accompanied it since.

Ashamed of her own exposure, she feared that stigma also pass to her grandchildren.

“If people knew that my son died of leukemia, especially before they [netos] If they get married, others could not want to marry them, “Nakamura shares.” I made sure my children understood that. We kept this in family and we didn’t tell anyone as he died. ”

But encouraged by other survivors, he finally spoke publicly about his son’s cancer in 2006, three years after his death.

“I received phone calls and even letters from people who heard my story. This made me realize the severity of the hereditary effect on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” he said.

Even though now knowing that it is unlikely to have been causing the son’s cancer, says that, as a mother, the feeling of guilt is a burden that will carry forever.

“I’m still sorry. I still apologize to you. I say, ‘Forgive me.’

Children who have never come

Mitsuko Yoshimura, now 102, always dreamed of having a big family – but never managed to have children Photo: Futa Harm, Cnn

The unique burden of Hibakusha maternity is something Mitsuko Yoshimura, now 102, never carried.

Separated from parents and sister still young, he always wanted to have a family. He moved to Nagasaki looking for a good job at the Mitsubishi Treasury Department-a few months before the US launched the bomb, turning the city into a hell on Earth.

“When I arrived on the road, there were people with blood gushing their heads, people with their skin torn from their backs,” he recalls.

Yoshimura married another bombardment survivor an ano after the end of World War II, hoping a new beginning Foto: Futa Nagao, CNN/Cortesia de Mitsuko Yoshimura

Being only one kilometer of the epicenter of the explosion, its survival was a real miracle. In the following months, he was left behind to help the injured. But your body also suffered.

“My hair fell. Whenever I tried to comb it with my hands, strands slowly came out,” says Yoshimura. It also vomited blood regularly over months after the explosion.

Still, he resisted. He married a year after the end of the war. Her husband was an atomic bomb survivor, like her, and the marriage marked a new start to the couple.

But the son who wanted so much was never born. It had two spontaneous miscarriages and one lord.

Yoshimura’s niece, Saori Hayasaki, a third generation survivor, learns about her family’s past with her Photo: Futa Harm, Cnn

Today, Yoshimura lives alone; Her husband passed away years ago. At his home in Nagasaki, where there are photos of children and grandchildren, there are dolls – a silent substitute for what was lost, he says.

With his remarkable age, Nakamura and Yoshimura know they don’t have much more life. But this gives them greater urgency to educate younger generations about the cost of a nuclear war.

“People really need to think carefully. What do victory or defeat bring? Wanting to expand the territory of a country, want a country to gain more power, what do people seek exactly with it?” Asks Nakamura. “I don’t understand. But what I feel deeply is the complete foolishness of war.”

Credits

Journalist

Hanako Montgomery

Editors

Sheena McKenzie, Todd Symons

Producer

Junko Ogura

Senior video producer

Insert anoushfar

Visual Publisher

Carlotta Dotto

Video Editors

Estefania Rodriguez, Daishi Kusunoki