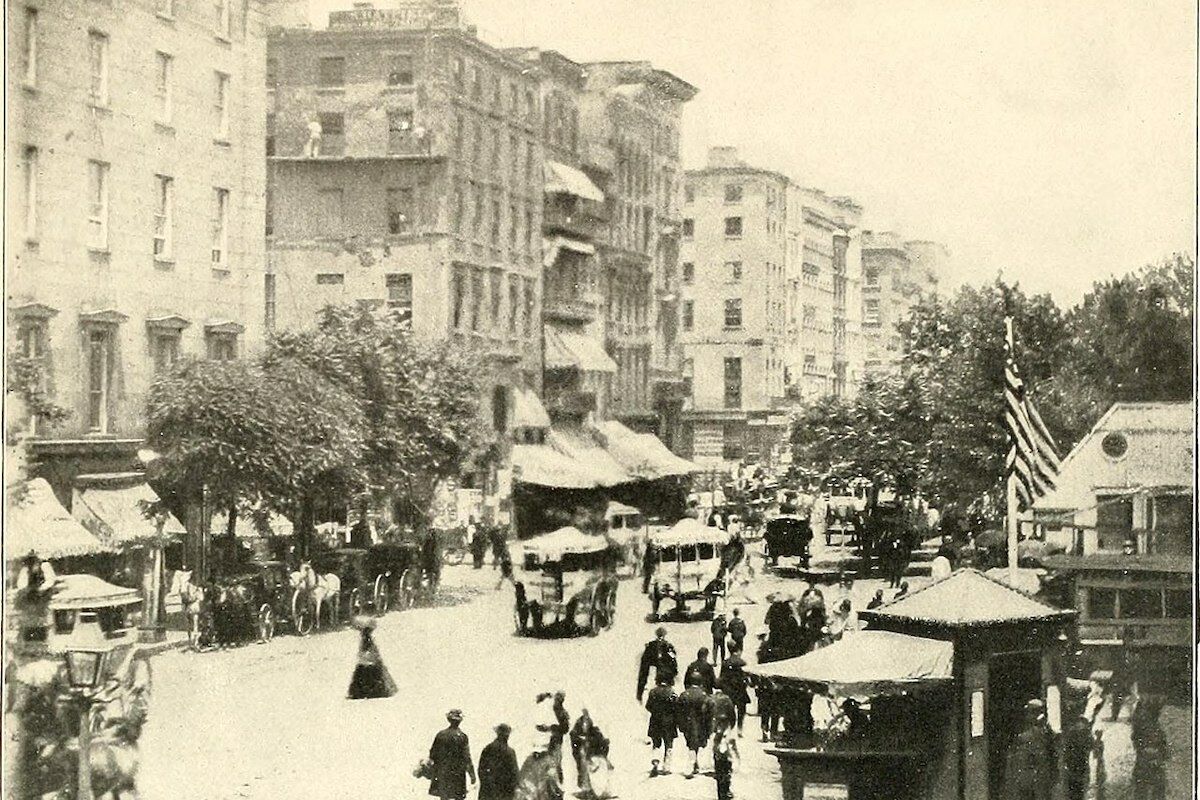

New York, at the beginning of the civil war, in 1861. Although it was never approved, New York prepared a law similar to those of other cities in the country

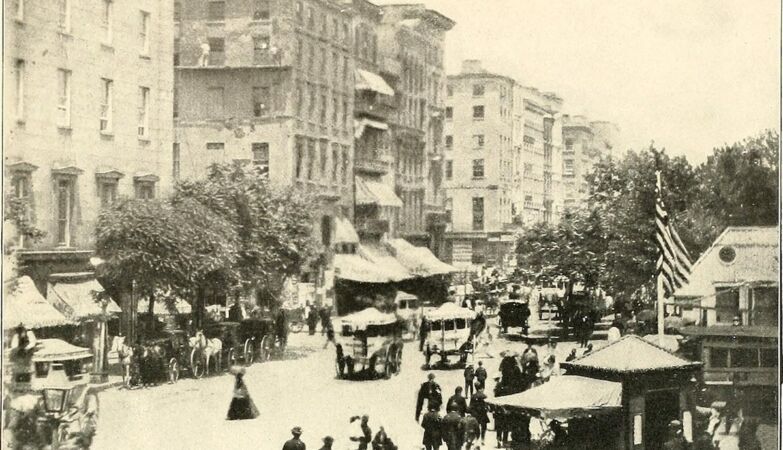

After the civil war, several US cities applied laws that prohibited deformed or mutilated people from being seen in public.

“It’s better to be beautiful than good.”

When Irish poet and writer Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) pronounced this sentence, it seems that he was thinking in the United States of his day.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, several cities and at least one state of the United States promulgated a series of laws that made a crime not having certain physical characteristics or have other characteristics that were against the predominant aesthetics of the time.

Over time, these controversial regulations, which included fines and prison sentences, became known as “FEIRA LAWS“.

Hide the “unpleasant”

“The so -called ‘laws of ugliness’ were a series of municipal decrees that prohibited the presence of people with certain physical characteristics in public places,” Mundo Susan Schweik, Dean of Arts and Humanities at Berkeley.

The first of these regulations was approved in the city of San Francisco in 1867, added the American teacher, who conducted an exhaustive study of these regulations for her book The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (The laws of ugliness: disability in public).

The Californian City Ordinance criminalized any “sick, mutilated or deformed in some way To the point of becoming a disgusting or repulsive object ”seen in the streets, squares, parks and other public places.

Over the years, cities such as Reno (Nevada), Portland (Oregon), Lincoln (Nebraska), Columbus (Ohio), Chicago (Illinois), New Orleans (Louisiana) or the state of Pennsylvania copied the spirit and lyrics of the text dictated in San Francisco.

In the case of Chicago, one of the last cities to approve such regulation in 1916, the argument presented by the local authorities was that of “Remove” all “ugliness from the streets”reported the local newspaper Tribune.

“It seems that the ‘ugliness’ in question referred to inanimate objects, such as piles of bricks, but the obstructions they wanted to eradicate were human,” added Schweik.

At the time, some justified measures as a way to control disease and protect public health.

“A Thesis of ‘maternal influence’ He suggested that if a pregnant woman saw someone sick, mutilated or deformed, she would be so impressed that her baby could be born sick, ”he explained.

Proof of this belief can be found in the text published in 1906 by American cleric Charles Henderson.

“O epileptic is an object of terrorand no one who has witnessed a person to convulsion can escape the haunting memory of the spectacle and completely free his mind from terror or aversion, ”he wrote, supporting measures to isolate the” unwanted. “

In the postwar period

For Schweik, the fact that these laws began to be approved two years after the end of the civil war (1861-1865), which left thousands of injuries and mutilated across the country, it was no coincidence.

A striking element is that many of these “ugliness laws” were supported by charity organizations.

“These rules were used to institutionalize people considered disgusting“BBC Mundo Raquel Mangual, a researcher at the Temple University deficiencies institute.

The various rules provided penalties as Fines and Prison for “sick, mutilated or deformed people” who were exposed to the public.

“The consequence was that the people to which these ‘laws’ were applied were forced to enter nursing homes or charities. And that was a non -official life -arrest sentence, ”said Schweik.

The poor were the target

Although the “laws of ugliness” seemed to have the purpose of pursuing certain groups for their aesthetics, or lack of it, the experts consulted indicated that, in fact, they had a different purpose.

“These rules had very little to do with physical attractiveness and were used to Take people with disabilities off the streetshomeless or suffering from diseases such as epilepsy, ”Mangual explained.

Guy Caruso, an expert on intellectual and developmental disabilities, spoke in similar terms.

“Homeless people, disabled or mutilated, were mostly poor who had to be begged to survive and people were repulsed by seeing them on the streets,” said Temple University professor.

But the ordinances not only sought to hide people considered “unpleasant or disgusting”, prohibiting them from being on streets, squares or parks, as well as They made their livelihood difficultforbidding them from requesting alms.

The Chicago rule, for example, provided for dollar fines (more than 15 euros in current values) for each infraction by a “sick, mutilated or deformed person” displayed in public places.

Open the doors for discrimination

Although the number of people to which the rules were applied is unknown, as neither the police nor the courts kept records, the experts consulted stated that their impact transcended the victims.

“These laws were part of a set that intertwined with a group of laws that emerged in the late nineteenth century control the type of people That you wanted to allow in public spaces, ”said Schweik.

The expert claimed that the ordinances were eventually linked to Racial segregation laws approved in the southern US.

Mangual said the instruments also opened the doors for eugenic legislation approved by some states in the late nineteenth century.

“These laws facilitated the approval of other laws that authorize sterilization Of people with disabilities or mental illness in order to eradicate these groups, ”he added.

Schweik admitted that the “laws of ugliness” served to discriminate against people with disabilities, but clarified that this was not their main goal.

“I often say that (former president) Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) was not the target of these rules. The main target was the poor people“He insisted.

In 1921, at the age of 39, Roosevelt suffered from polio, a disease that paralyzed him from the waist down and forced him to use a wheelchair for the rest of his life. However, his condition was hidden and, at certain public events, used crutches and other devices to stand up.

Dead but not forgotten

With the arrival of the 20th century, the application of the “laws of ugliness” became quite unusual. However, they They were not revoked until the 1970sthanks to the pressure of the movement for the rights of the disabled.

“In 1970, in the city of Omaha (Nebraska), a police wanted to arrest a homeless, but had no reason to do so, because the man was not requesting alms, drunk or disorder.

“A judge rejected the police claim, saying,” Should I allow my neighbor’s children to be arrested if they are ugly? A local newspaper has published the story, and activist groups began to organize to demand the revocation of the rule, “he continued.

“By the way, the headline used by the newspaper: ‘Legal Law only punishes the ugly‘This is why we know these instruments today as’ laws of ugliness’. This, despite the fact that the ugly word does not appear in any of them, ”he concluded.

And while not all cities have revoked their laws, the approval of the Americans with disabilities (ADA) by the US Congress in 1990 made them ineffective in practice. ADA prohibits any kind of discrimination against people with physical or intellectual disabilities.

Despite the official revocation of the rules, experts claim that consequences were not overcome.

“The spirit of these laws is still rooted in the subconscious of people and institutions and this is seen in the way people with disabilities are treated today, as they are still seen as if they were children,” said Mangual.

Schweik also stated that “the culture of the ‘laws of ugliness’ It’s still very alive”And said the current US President Donald Trump is one of those who contributed to it.

“Trump forged his political career in the early 1990s to campaign against the homeless and disabled in the tributary fifth Avenida de New York, which made him resentful because that ‘degraded’ the area around Trump Tower“He remembered.

“Today, instead of decrees, cities are using more subtle ways to keep people away from others, such as the installation of banks and other street furniture in squares and meter or train stations that prevent beggars from staying for a long time or sleeping in these places,” he said.