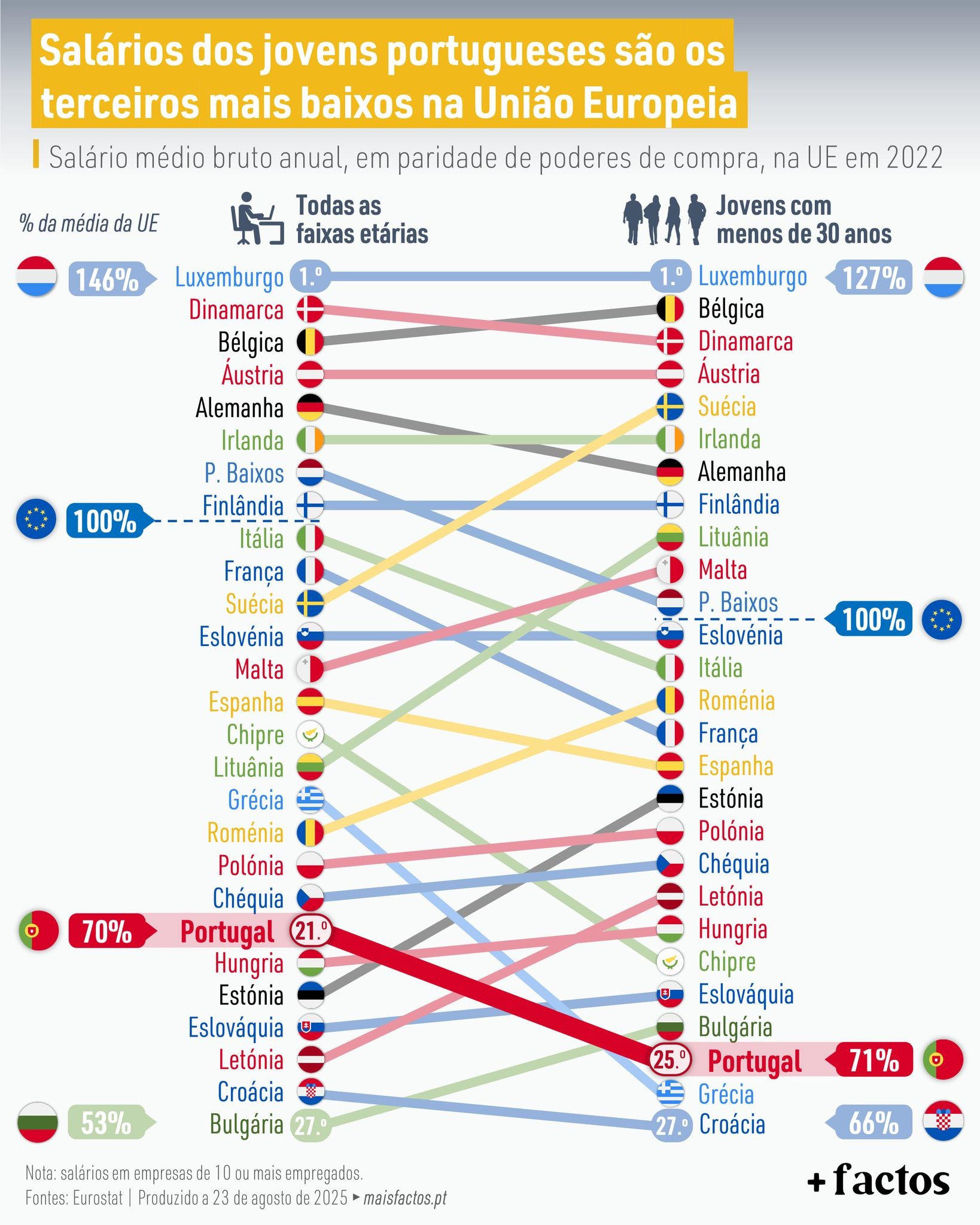

Unsurprisingly, wages are low in Portugal. In 2022, according to the Eurostat (Structure of Earnings Survey), the annual gross average salary adjusted to purchasing power represented only 70% of the EU average – among the worst in Europe. The purchase powers (PPC) metric eliminates price differences and exposes a structural disadvantage.

Among the younger ones, the portrait is even more worrying. For workers under 30, the PPC annual gross average salary corresponds to 71% of the European average, placing Portugal in 25th position among the 27 Member States (3rd worst). This translates into postponed autonomy, difficulties in access to housing and greater propensity to qualified emigration.

There are identified factors that help explain the differential: relatively low productivity, strong weight of micro and small companies with compressed margins and high context costs (tax, bureaucracy, regulatory uncertainty). Studies show, for example, that the gross operational margin of non -financial companies is the lowest in Europe, which limits sustained salary increases and competitiveness.

Nevertheless, there are recent signs of nominal recovery. In 2024, the average remuneration per worker grew 8.0% according to Banco de Portugal, reflecting the minimum wage update and some recovery of purchasing power compared to inflation, with a real gain estimated at 5.3%. It is an important but insufficient relief to close the distance to the European average.

If we want higher salaries – especially for young people – the route is known: raise productivity (education, qualification and technology), promote business scale and investment, reduce bureaucracy and make the statement more competitive, ensuring more dynamic housing and work markets. Lasting salary gains are born of growing economies that grow more and better – this should be the focus.

- The facts seen to the magnifying glass by André Pinção Lucas e Juliano Ventura – A partnership of the postcard with the Institute

Also read: