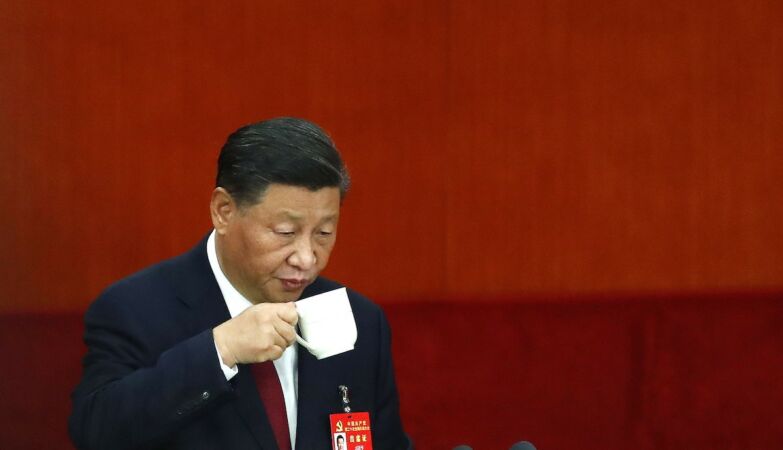

Mark R. Cristino/EPA

From the growth of industry that decimated Western competition or the early bet on renewable energy that is now bearing fruit, China’s five-year plans are likely to have repercussions on the global economy.

China’s top leaders meet this week in Beijing to outline the country’s goals and priorities for the remainder of this decade. The decisions taken at the Plenary of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party will serve as the basis for the next five year planwhich will guide the second largest economy in the world between 2026 and 2030.

The full plan will only be released next year, but authorities are expected to bring forward some guidelines on Wednesday. Experts say that the Chinese model, guided by planning cycles rather than elections, tends to produce decisions with global impact.

“Five-year plans define what China wants to achieve, indicate the direction the leadership intends to take, and mobilize state resources to achieve these predefined goals,” says Neil Thomas, a Chinese policy researcher at the Asian Society Policy Institute.

At first glance, the image of hundreds of de facto bureaucrats shaking hands and drawing up plans may seem monotonous. History, however, shows that their decisions often have deep repercussions.

Here are three moments when China’s five-year plan reshaped the global economy.

1981-84: “Reform and Opening”

It is difficult to pinpoint when China began its path to becoming an economic power, but many members of the Chinese Communist Party will say that it was in December 18, 1978.

For almost three decades, the Chinese economy was tightly controlled by the state. Soviet-style central planning failed to increase prosperity, and much of the population still lived in poverty.

The country was recovering from Mao Zedong’s devastating government. The Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), campaigns led by the founder of communist China to reshape the economy and society, resulted in the deaths of millions of people.

When speaking at the Third Plenary of the 11th Committee, in Beijing, the then new Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping, declared that it was time to adopt some elements of the market economy. His policy of “reform and opening up” became central axis of the five-year plan following, started in 1981.

The creation of special economic free trade zones, and the foreign investment they attracted, transformed Chinese lives.

According to Thomas, from the Asian Society Policy Institute, the objectives of that five-year plan could not have been achieved more emphatically.

“Today’s China goes beyond the wildest dreams of the people of the 1970s, in terms of restoring national pride and consolidating their place among the great world powers”, he states.

The process also reshaped the global economy. In the 21st century, millions of industrial jobs from the West were transferred to new factories in the coastal regions of China.

Economists called this phenomenon the “China shock”, which ended up fueling the rise of populist parties in former industrial areas of Europe and the United States and led to measures such as the imposition of tariffs and retaliations promoted by American President Donald Trump — who says he is trying to recover industrial jobs lost to China in previous decades.

2011–15: “Emerging strategic industries”

China’s status as “factory of the world” was consolidated with its entry into the global international organization that deals with the rules of trade between nations, the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 2001. But, at the turn of the century, the Chinese Communist Party was already planning the next step.

There was a fear that the country would fall into the so-called “middle income trap”, when a rising nation stops offering cheap laborbut still does not have the innovation capacity to produce goods and services with high added value.

To avoid this, China began investing in so-called “emerging strategic industries“, a term first used officially in 2010. The focus included green technologies such as electric vehicles and solar panels.

As climate change gained prominence in Western politics, China mobilized unprecedented resources to boost these new sectors.

Today, China is global leader in renewable energy and electric vehiclesin addition to controlling almost the entire supply of rare earths needed for the manufacture of chips and the development of artificial intelligence (AI).

The world’s dependence on these resources gives China a position of power. The recent decision to restrict rare earth exports led Trump to accuse China of trying to “hold the world hostage“.

Although “emerging strategic forces” were incorporated into the 2011 five-year plan, green technology had already been identified as a potential driver of growth and geopolitical power by then Chinese leader Hu Jintao in the early 2000s.

“The desire to make China more self-reliant in economics, technology and freedom of action goes back a long way, it is part of the very essence of the ideology of the Chinese Communist Party”, explains Thomas of the Asian Society Policy Institute.

2021-2025: “High-quality development”

This may explain why in recent five-year plans, China began to prioritize the so-called “high-quality development”, a concept formally introduced by Xi Jinping in 2017.

The goal is challenge US technological dominance and place China at the forefront of the sector.

Domestic success stories such as video app TikTok, telecommunications giant Huawei and artificial intelligence model DeepSeek illustrate Chinese advancement.

China’s progress, however, is viewed with suspicion by Western countries, who consider it a threat to national security. Bans and restrictions on Chinese technologies have affected millions of users and provoked diplomatic disputes.

Until now, Chinese technological advancement has depended on American innovations, such as Nvidia’s advanced semiconductors. With the ban on the sale of these components to the country imposed by the Trump administration, it is likely that the concept of “high quality development” will evolve into that of “new quality productive forces“, a new motto introduced by Xi in 2023, which shifts the focus to national pride and the country’s security.

This means placing China at the forefront of chip production, computing and artificial intelligence, without being dependent on Western technology, in addition to being immune to embargoes.

A self-sufficiency in all sectorsespecially at the highest levels of innovation, must be one of the central pillars of the next five-year plan.

“National security and technological independence are today the defining mission of China’s economic policy,” explains Thomas of the Asian Society Policy Institute. “Once again, this speaks to the nationalist project that underpins Chinese communism, ensuring that the country will never again be dominated by foreign powers.”