Johnica Winter

New research analyzed prehistoric feces from the Loma San Gabriel culture and discovered that intestinal infections were a constant.

A new report published in PLOS One has uncovered evidence of harsh living conditions in the Cave of Dead Children in the Zape River Valley near Durango, Mexico. The research concluded that the population of the prehistoric culture of Loma San Gabriel frequently suffered from intestinal infections caused by a variety of pathogens.

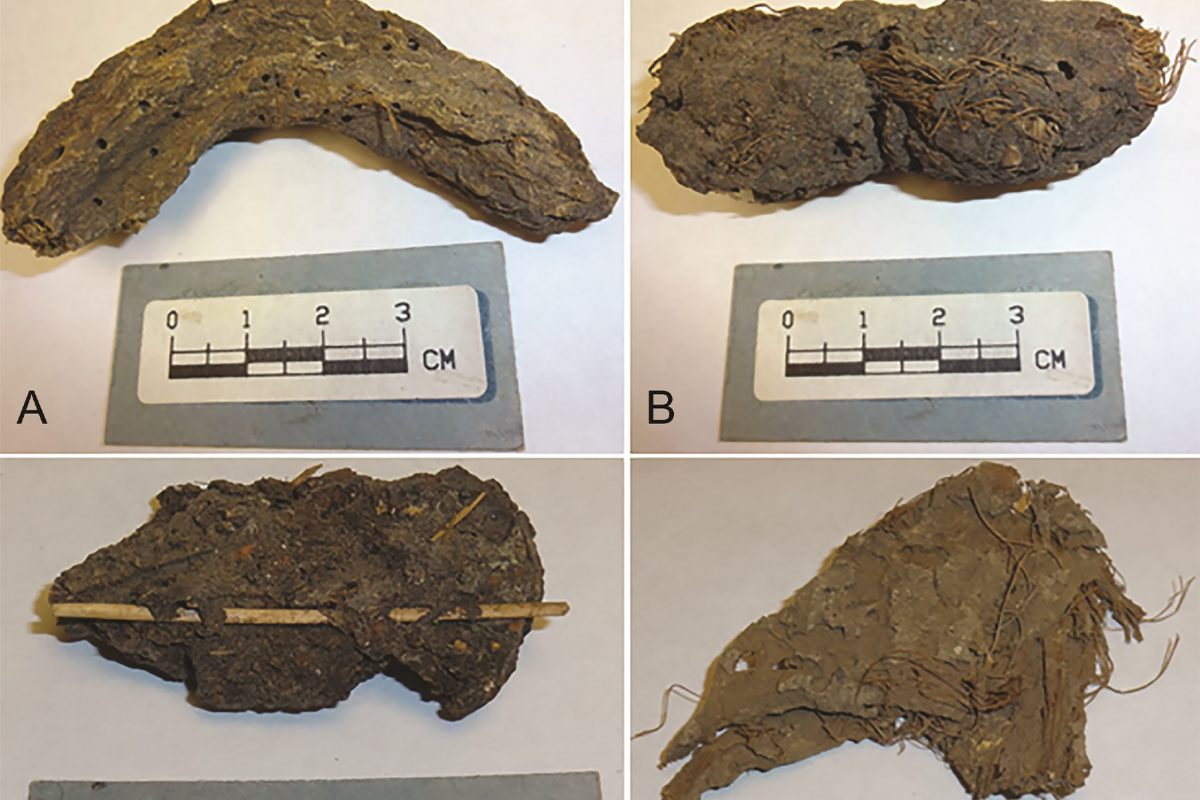

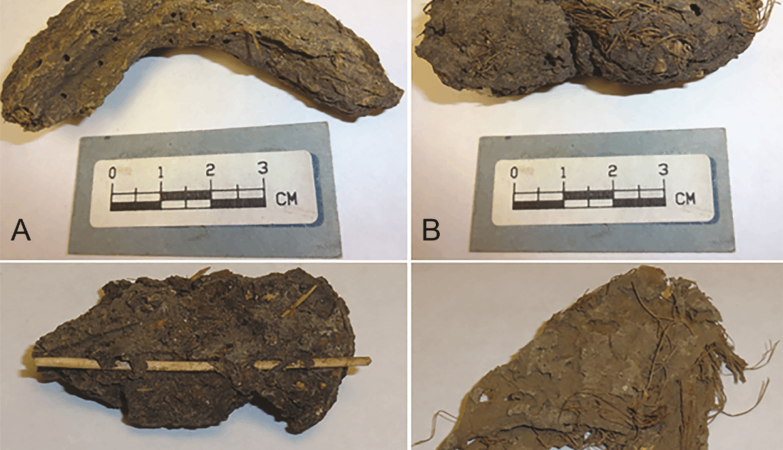

The research team, led by Drew Capone of Indiana University, analyzed 10 samples that are 1300 years old of paleofeces recovered decades ago from the cave. “Working with these ancient samples was like opening a biological time capsule,” said Capone, noting that each sample revealed “insights into human health and everyday life.”

The cave, excavated in the 1950s, was a place of rituals and domestic activities for the people of Loma San Gabriel, who practiced small-scale agriculture, produced characteristic ceramics and, at times, performed child sacrificeshence the name of the cave. Previous microscopic studies of fecal remains from the site had already identified eggs of parasites such as hookworms, whipworms and pinworms, recalls .

In the new study, researchers used advanced molecular techniques, including DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to identify a broader range of ancient pathogens. Analysis revealed that each sample contained at least one disease-causing microbesuggesting widespread intestinal infections among the population.

The most common pathogens were the Blastocystis parasite, which causes gastrointestinal discomfort, and multiple strains of Escherichia coli (E. coli), detected in around 70% of the samples. The team also found genetic traces of Shigella, Giardia and pinworms, all associated with intestinal diseases.

According to the study, the abundance of microbes indicates poor sanitation conditions in the community, where people were likely exposed to fecal contamination through drinking watersoil or food. The researchers noted that some pathogens may have broken down over time, meaning actual infection rates may have been even higher.

Co-author Joe Brown of the University of North Carolina said the findings demonstrate the “potential of modern molecular methods to support studies of the past“, revealing how ancient disease patterns reflect modern public health challenges.