More than two centuries after Napoleon Bonaparte’s disastrous campaign in Russia, scientists have managed to identify new biological causes that contributed to the collapse of the French army.

A study published on Friday (24) in the journal Current Biology, and released by CNN Internationalrevealed that the soldiers faced multiple infectious diseases, not just typhus, as previously believed.

The researchers analyzed DNA samples preserved in the teeth of soldiers found in a mass grave in Vilnius, capital of Lithuania, and detected two bacteria previously not associated with the episode: Salmonella enterica, which causes paratyphoid fever, and Borrelia recurrentis, responsible for recurrent fever.

FREE LIST

10 small caps to invest in

The list of stocks from promising sectors on the Stock Exchange

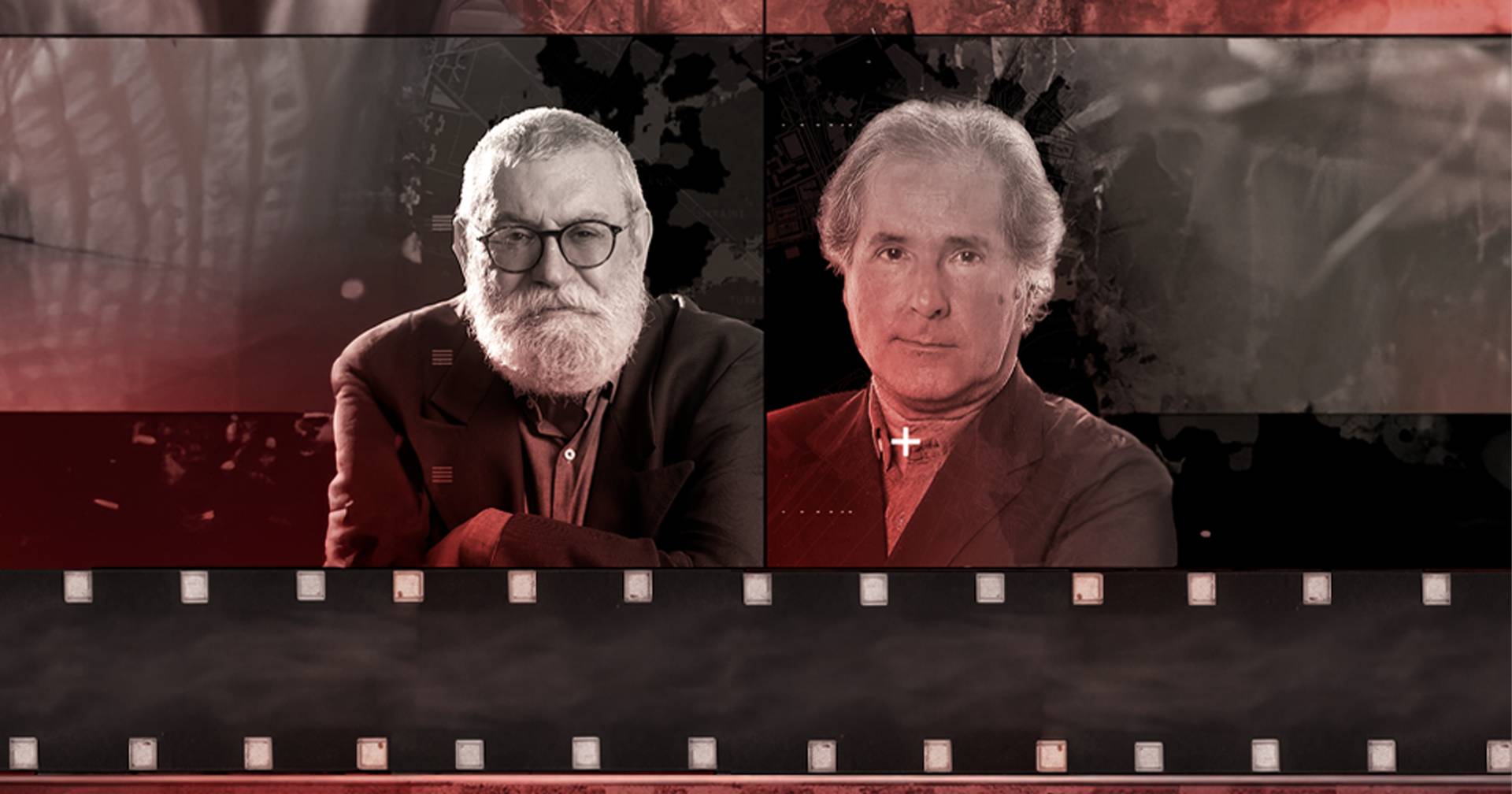

“We previously believed that typhus was solely responsible for the decimation of Napoleon’s army,” explained Rémi Barbieri, former researcher at the Pasteur Institute and current member of the University of Tartu, in Estonia. “But we found evidence of a much more complex scenario, with several infections acting at the same time.”

Collapse of troops

When Napoleon began his invasion of Russia in 1812, his army numbered around 500,000 soldiers. Six months later, only a few tens of thousands returned to France. Deaths were attributed to battles, extreme cold and starvation, but new evidence indicates that disease also played a decisive role.

Upon arriving in Moscow, the troops found an empty city, burned crops and a lack of food and clean clothing, an environment conducive to the spread of infections. “It was a real cauldron of diseases”, summarized Barbieri.

Continues after advertising

Technology and discovery

The research used high-precision genetic sequencing, capable of identifying extremely degraded DNA fragments. This technological advance allowed scientists to reconstruct the soldiers’ microbiome and detect pathogens invisible in previous studies.

“These powerful machines allow us to understand much more clearly the scenario of past infectious diseases,” said Nicolás Rascovan, study supervisor and head of the Microbial Paleogenomics Unit at the Institut Pasteur.

Although the team found no traces of typhus in the samples analyzed, Rascovan highlighted that the small sample — just 13 individuals — is not enough to rule out the presence of the disease in other parts of the army.

Lessons for the present

For scientists, the study goes beyond historical curiosity. He shows how ancient DNA can reveal interactions between wars and epidemics and help understand the evolution of pathogens that still circulate today.

“We are at a time when ancient DNA offers us a new lens through which to view history,” said Cecil Lewis, at CNNhistorical microbiome researcher at the University of Oklahoma. “This data helps us understand how diseases evolve and persist, which is vital for anticipating future threats.”

Today, both paratyphoid fever and relapsing fever still exist, but they are less common and less lethal. The disaster of 1812 left a lasting legacy: Napoleon’s decimated army marked the beginning of his political and military downfall in Europe.

Continues after advertising

“It is impressive to see how the advancement of technology allows us to discover today what was unimaginable 20 years ago,” concluded Rascovan.