It stopped being a promise and became routine in large companies. According to McKinsey, 78% of global organizations already use it in at least one business function. The telecommunications, finance and retail sectors lead this adoption, with rates between 30% and 40% actively, in addition to testing pilots or prototypes.

After 30 years of dedication to and “policy making”, I made one of the most exciting choices of my professional life: coming to Wharton, the University of Pennsylvania’s business school, to study the new frontiers of management and leadership.

One of the topics that has caught my attention the most so far has been the use and implementation of artificial intelligence in companies, an approach that combines technology, strategy and work psychology. My challenge has been to connect this organizational vision to what economics teaches about productivity, progress and inequality.

As Prof. showed us. Stefano Puntoni, although widespread, the adoption of artificial intelligence still does not seem to be accompanied by clear metrics. When asking executives how many monitored the return on investment in GenAI, almost no one responded. The race for efficiency is real; learning about its effects, not so much.

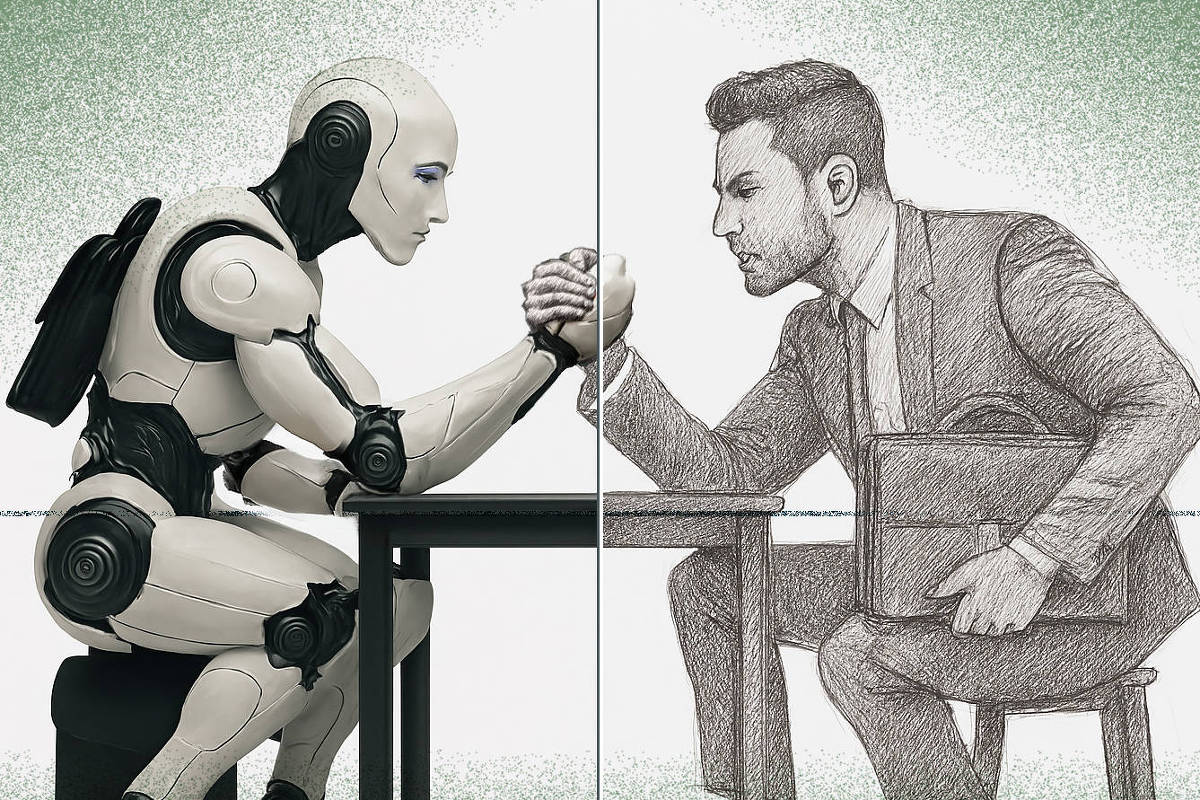

This mismatch reveals a central point: organizations will decide whether they want to use technology to replace people or to expand their capabilities. The first option generates quick and superficial gains; the second creates lasting innovation and trust.

As Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson remember in , technological advancement has never been automatically synonymous with prosperity. During a thousand years of history, economic power was reorganized around machines. And not always in favor of the majority.

When technology serves to concentrate control, it increases inequalities; when it is designed to distribute opportunities, it promotes well-being and growth. Progress is neither linear nor neutral: it is the product of human and institutional decisions.

Today, this choice is repeated. Generative AI redefines tasks and roles, but also challenges the meaning of work. By automating what once expressed human talent, it can erode the sense of competence. By imposing standardized processes, it reduces autonomy. And, by replacing human interactions with algorithms, it weakens belonging.

There are three dimensions that, according to work psychology, support well-being and productivity. AI can shorten the arduous journey of learning, the one that develops instinct, judgment and experience. Efficiency should not replace maturity.

The evidence is eloquent. Research by Puntoni and other authors shows that workers evaluated by algorithms show less empathy and willingness to help colleagues. According to statistical tests, consumers, in turn, value products more when they perceive human participation in their creation.

The technology is the same; Interaction design is what changes everything. Choices about AI happen across multiple decision layers — from teams to boards, from algorithms to regulation. Making them explicit is essential for culture to be translated into ethical standards and metrics.

But AI can also open a new cycle of opportunities. As Prof. showed us. Christian Terwiesch, generative AI can transform the innovation process itself. Instead of restricting decisions to a few, it allows more people to create, test and propose solutions supported by AI; what he calls “innovation tournaments.” The human role, in this context, would be that of curator, not executor.

GenAI helps create more and better ideas, faster, but it still needs people to provide direction, purpose and value judgment. Companies that know how to balance these forces between machine speed and human judgment will open new horizons of competitive advantage.

The future of innovation, therefore, does not just belong to technology, but to the culture that surrounds it. Companies that combine structured processes of experimentation with freedom to imagine will create not just products but meaning.

And perhaps this is the true promise of AI: giving people back the time and energy they need to think, create and reinvent what progress should really be. Progress is fast, and just transition policies are becoming urgent, including to support those who will be most affected and create conditions for continuous relearning.

But ultimately, these choices will not be made in a vacuum. They will be shaped by economic incentives, public policies and the way in which markets value —or not— investment in people.

If the system only rewards short-term productivity gains, the use of AI will tend toward substitution and concentration. If, on the contrary, it rewards the creation of human value and the dissemination of knowledge, technological advancement could become a new engine of shared prosperity. The economic balance of this new era will be in combining productivity with human development; efficiency with learning.

The challenge, therefore, is not just for companies, but also for regulation: making technical progress go hand in hand with economic and social progress.

Artificial intelligence can generate abundance or inequality. What will determine the result is not the algorithm, but the set of choices, incentives and values built around it.

LINK PRESENT: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click the blue F below.