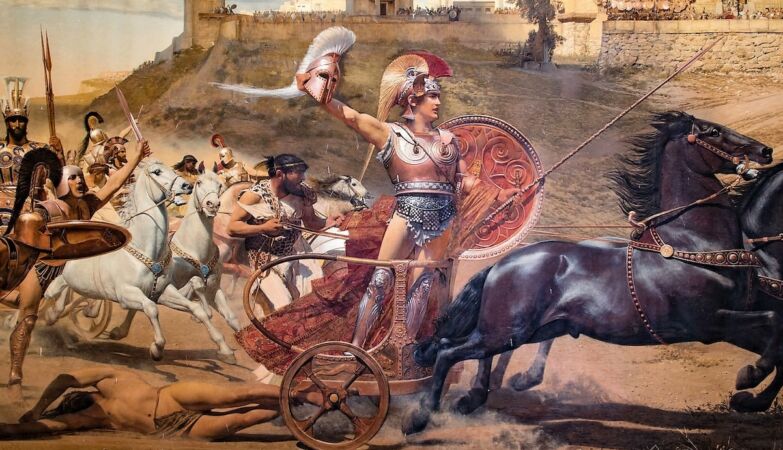

Achilles, the hero to whom we owe our tendon’s name

Buried in his body is a tribute to a long-dead Italian anatomist — and he’s not the only one. He walks around with strangers’ names sewn into his bones, brain and organs. We all walk.

Some of these names sound like myths. The Achilles tendon, the band on the back of the ankle, pays homage to a Greek hero struck down by an arrow in his weak spot.

The Adam’s apple refers to a certain biblical bite into a forbidden fruit. But most of these names are not mythical. They belong to real people — mostly European anatomists from centuries ago — whose legacies endure every time someone opens a medical manual.

They are called eponyms: anatomical structures named after people rather than being described for what they really are.

Let’s take the fallopian tubes. These small canals between the ovaries and the uterus were described in 1561 by Gabriele Falloppio, an Italian anatomist fascinated by tubes, who also gave his name to the Fallopian canal in the ear.

Gabriele Falloppio (1523–1562) was an Italian anatomist and surgeon who described the Fallopian tubes in his work Observationes Anatomicae (1561).

Or in Broc areaa, named after Paul Broca, the 19th century French doctor who associated a region of the left frontal lobe with speech production. If you’ve ever studied psychology or know someone who’s had a stroke, you’ve probably heard their name.

Then there is the Eustachian tubethat little channel that opens when we yawn on a plane. It was named after Bartolomeo Eustachi, the Pope’s doctor in the 16th century. All these men left fingerprints on our anatomy — not in the flesh, but in the language.

Why have we kept these names for centuries?

Because eponyms are more than medical curiosities — they are intertwined in the culture of anatomy. Generations of students recited them in amphitheaters and wrote them down in notebooks. Surgeons mention them in the middle of an operation as if they were talking about old friends.

They are short, sonorous and familiar. “Broca’s Area” is said in two seconds. The descriptive alternative — “posterior inferior frontal gyrus” — sounds like a spell. In busy clinical settings, brevity often wins.

Furthermore, eponyms come with stories, which makes them easier to memorize. Students remember Falloppio because it sounds like the name of a Renaissance musician. They remember Achilles because they know where to aim the arrow. In a field dominated by Latin, a human story serves as a useful hook.

And, of course, there is tradition. Medical language is based on centuries of scholarship. For many, eliminating eponyms would be like tearing down history itself.

Or shadow side two eponyms

But there is a darker side to this linguistic relationship. Despite their charm, eponyms often miss the main point: they rarely say what a structure is or what it does. “Fallopian tube” reveals nothing about its function or location. “Uterine tube”, yes.

Eponyms also reflect a narrow version of the story. Most emerged during the European Renaissance—a time when “Discovering” anatomy often meant claiming knowledge that already existed elsewhere. The figures celebrated are overwhelmingly white European men. The contributions of women, non-European scholars and indigenous knowledge are practically invisible in this language.

And there are truly uncomfortable cases: some eponyms pay homage people with horrible pasts. A “syndrome by Reiter“, for example, was named after Hans Reiter, a Nazi doctor who conducted brutal experiments on Buchenwald prisoners. Today, the medical community uses the neutral term “reactive arthritis,” a small but significant refusal to celebrate someone who caused suffering.

Each eponym is a small monument. Some are historical curiosities; others, monuments that perhaps we would prefer to let fall into oblivion.

Descriptive names make more sense

Descriptive terms, in contrast, are clear, universal, and useful. There’s no need to memorize who discovered something — you just need to know where you are and what you do.

If you hear “nasal mucosa”, you immediately know that it is inside the nose. But if someone asks you to locate the “Schneider’s membrane”you will probably not know what to answer.

Os Descriptive terms are easier to translate, standardize and searchr. They make anatomy more accessible to students, clinicians and the general public. And, above all, they don’t glorify anyone.

What to do with all these old names?

There is a growing movement to phase out eponyms—or at least use them alongside descriptive terms. The International Federation of Anatomists’ Associations (IFAA) recommends the use of descriptive terms in teaching and writing, keeping eponyms in parentheses.

This doesn’t mean erasing the history books — it means adding context. We can teach the story of Paul Broca by recognizing the bias present in naming traditions. We can remember Hans Reiter not by associating his name with a disease, but as a historical warning.

This dual approach allows preserve history without letting it dictate the future. It makes anatomy clearer, fairer and more honest.

The language of anatomy is not just academic jargon—it is a map of power, memory and legacy engraved in our flesh. Whenever a doctor says “Eustachian tube,” it echoes the 16th century. Every time a student learns “fallopian tube,” they move closer to clarity and inclusion.

Perhaps the future of anatomy does not involve erasing old names, but understanding the stories they carry — and deciding which ones deserve to be kept.