Australia’s driest desert is blooming again after a historic flood that is attracting birds, mammals and visitors from around the world

In satellite images, it looks like a collection of large smudges of blue and green paint – spreading, flowing, penetrating the brown paper of the desert. In the arid center of Australia, these patches represent a new inland sea, born from a flood that traveled hundreds of kilometers through the veins of a gigantic, parched continent. The rare phenomenon is now bringing life back to the desert, attracting mammals, birds and tourists to the heart of the Australian outback.

“Imponderable” – this is how ecologist Richard Kingsford, from the University of New South Wales, describes the possibilities for scientific discovery opened up by this sudden oasis in one of the driest regions on the planet.

“It’s the water birds, the spectacular current of water crossing the middle of the desert. It’s the fish in the rivers. And it’s also the following months, when carpets of wildflowers cover the desert”, he says. “Rare events are not well understood precisely because they are rare. We don’t know for sure how big this flood will be.”

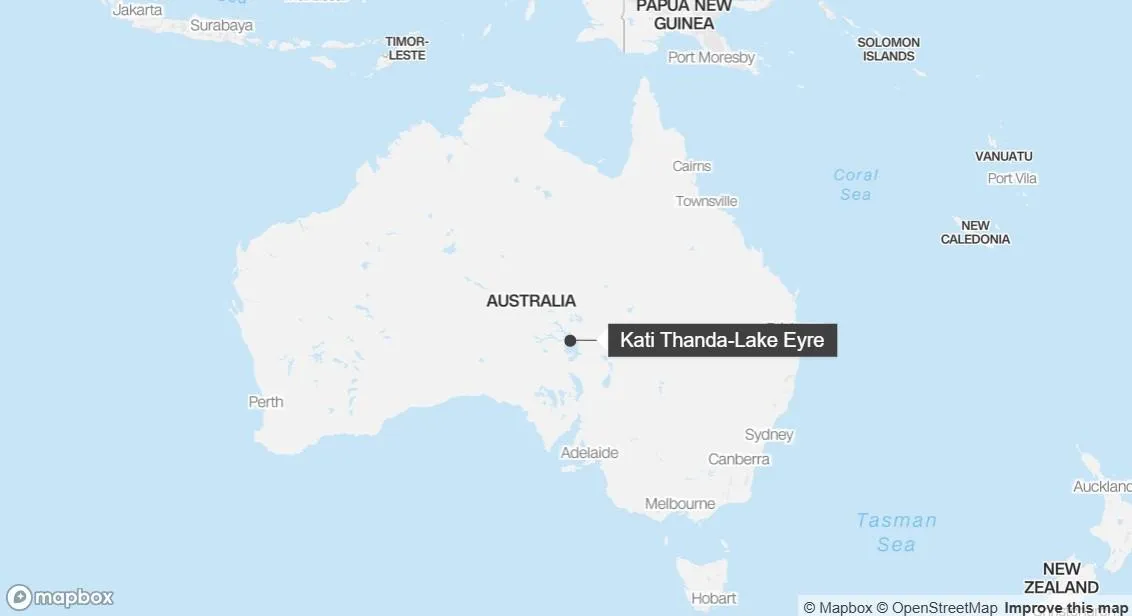

Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre is an ephemeral lake measuring 9,500 square kilometers and, despite its name, it is rarely full. It receives an average of just 14 centimeters of rain per year and can be described more as a gigantic salt flat in the South Australian desert. In 1964, British land speed record holder Donald Campbell used the dry lake bed as a race track, then achieved a world record speed of 648 km/h on the vast, uninterrupted white surface.

Ten years later, in 1974, the lake filled completely for the third time on record. This flood became the highest water level mark – never repeated, although smaller floods have been observed in recent years. This year, after Tropical Cyclone Alfred dumped rain on inland Queensland in March, water rushing down Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre appears to be filling it for the fourth time in 160 years.

This animation, made up of 16 images captured by NASA’s Terra satellite, shows the evolution of Lake Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre between April 29 and June 12. (Image: NASA)

“A huge tourist boom”

Two major river systems feed the lake: the Georgina-Diamantina River, which began filling north of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre in May, and the Cooper Creek system. Cooper Creek, somewhat erroneously named by British explorer Charles Sturt, is far from just a stream. “During a flood, it can be between 60 and 80 kilometers wide,” explains Richard Kingsford.

The water brought by this second system has not yet reached the lake and may not have its full effect before October. When it finally arrives, the desert ecosystem will experience the explosive extremes of its cycle of abundance and scarcity. Shrimp and crustaceans will spawn, fish populations will soar, mammals like the endangered plume-tailed mulgara rat and the dusky jumping rat will have the opportunity to reproduce. Pelicans, mosquitoes and other waterfowl will arrive from as far away as China and Japan. The dust and sand will turn green, blooming into vibrantly colored native shrubs.

A recent image shows flood waters passing through the Lake Eyre basin. “There is hope,” says Annemarie van Doorn, co-manager of the Kalamurina Wildlife Sanctuary. (Image: Annemarie van Doorn)

And birds won’t be the only ones to fly to this oasis. “There aren’t many wild places on Earth anymore, and this is one of them – wild and spectacular,” says Richard Kingsford. “These floods clearly attract countless local and international visitors to witness this phenomenon. They cause a huge tourist boom.”

But the increase in visitors has not been without growing pains, as the region adapts to its new popularity.

In February, the South Australian government announced a ban on walking on the lake bed, both to protect the fragile salt crust and surface and to prevent injuries in a remote area where medical help may be far away. The measure also respects the cultural practices of the Arabana people, who consider the lake sacred.

According to a recent report from public broadcaster ABC, however, some people continue to venture onto the lake bed due to a lack of signage highlighting the prohibition. The government has already promised to install new signs and infrastructure for visitors soon.

Distance as protection

Floods bring vegetation inland, as shown in this aerial photo of the Lake Eyre basin. (Image: Arid Air)

To serve the tourist market, operators like Phil van Wegen dedicate themselves to a life in the remote Australian outback. In Marree, a small town south of Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, Van Wegen runs Arid Air, a company that offers scenic flights over the huge lake in small Cessna propeller planes.

“The flight, the route we take, leaves people amazed,” he says. For him, the desert is “vast, ever-changing and spectacular.” “If anyone wants to come and see this, Marree is a relatively easy destination. We’re only about 700 kilometers from Adelaide, and there’s tarmac right outside the door.”

The Ghan railway line ran through Marree until the 1980s, ensuring a “busy little centre”, says Van Wegen. Today, he is one of around 50 to 60 residents and believes it is the great distances that help keep Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre pristine.

“It’s lucky it’s so remote. It’s so far from everything that no one touches it or explores it. It’s its own form of self-preservation.”

Natural rhythms

This does not mean, however, that Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre has no protectors.

Conservationists Annemarie van Doorn and Luke Playford watch over the region like sentinels. Together they manage the Kalamurina Wildlife Sanctuary, a 679,667 hectare property owned by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, situated on the eastern shore of the lake. The vastness of the territory they oversee can only be truly understood from the helicopter they use in their conservation work – the area they are responsible for is the size of the US state of Delaware.

When the region is dry and the roads are passable, they can reach the nearest supermarket – a nine-hour drive away, in the city of Port Augusta. Now, however, the floods have cut off the dirt roads that connect them to the rest of the world. They will remain in their desert home, isolated by water for months, possibly until the end of the year. The Royal Flying Doctor Service lands there once a month to check its condition.

“You can’t see anything around it. It’s so, so silent,” Annemarie van Doorn tells CNN International by phone. “There’s no light pollution, there’s no noise. And we look up and there’s a dingo walking around on the sand dune, and we think, ‘How lucky are we.’

Then there are other times when you have flies crawling into your nose and eyes, and it’s 48 degrees, and you think, ‘This is miserable,’ but you do everything for a great cause.”

The couple’s main cause is to keep the environment pristine – which mainly involves controlling the population of invasive wild animals, such as wild boars and camels. About two-thirds of the water that reaches Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre passes through Kalamurina, and the couple watch life transform their arid world.

“This is special because it is a natural event,” says Luke Playford. “It’s the biggest flood in 50 years and, although it has caused a lot of damage in Queensland, it is not a climate change-induced phenomenon. It is a unique occasion.” “It’s good news,” adds Annemarie van Doorn. “There is hope.”

That hope is shared by Richard Kingsford, the ecologist, who will join tourists, conservationists and other scientists on long journeys by road and air through the outback to glimpse a temporarily fertile desert.

“I’m a conservation biologist, and it’s often depressing to watch the world and what we do to it. But this gives me incredible optimism – to see this system still fulfilling its natural rhythms in such a spectacular way.”