A project to last decades and cost billions of euros envisages the recovery of a lot of territory

Flooded parks, submerged underpasses and streets swallowed up in knee-deep water – lower Singapore is no stranger to what experts call “nuisance flooding”, which, although troublesome, does not pose a major threat to people or property. But in a small island nation that prides itself on long-term planning, the recent floods are considered an omen of much worse things to come.

The Southeast Asian island state expects surrounding sea levels to rise by 1.15 meters by the end of the century. In a “high emissions scenario”, it could rise by up to 2 meters by 2150, according to the most recent government projections. Combined with extremely high tides and coastal storms, sea levels could sometimes exceed current levels by up to 5 meters – higher than the height of about 30% of Singapore.

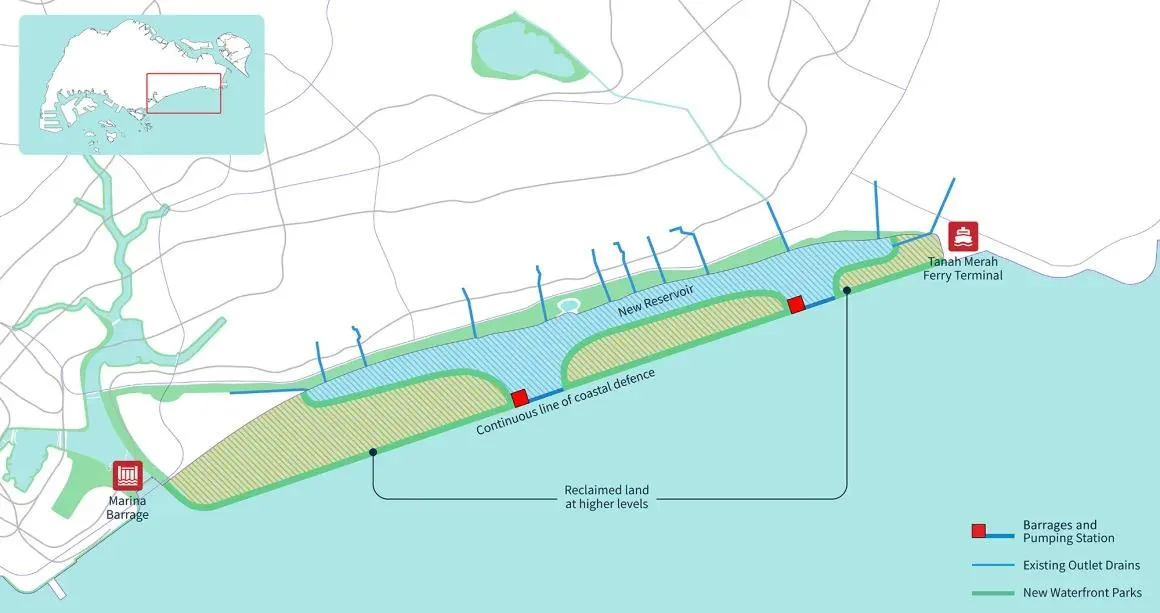

The proposed solution? A chain of habitable artificial islands around 13 kilometers long that will act as a sea wall, protecting the entire southeast coast of the country, which is 50 kilometers wide.

Named “Long Island” – a working title for now – the project is expected to take decades and cost billions of euros to complete. The plan calls for the recovery of around 8 square kilometers of land (two and a half times the size of New York’s Central Park) from the Singapore Strait.

The idea dates back to the early 1990s, although it has gained significant momentum in recent years. In 2023, Singapore’s urban planning agency, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), revealed an initial outline consisting of three parcels of land linked by tidal gates and pumping stations.

The proposed Long Island project would be built off the southeast coast of Singapore, a low-lying area. URA

Engineering and environmental studies are ongoing, so the shape and position of the islands remain subject to change. But there appears to be little doubt among those in charge that the plans will, in one form or another, move forward later this century.

“It’s a very ambitious proposal”, considers Adam Switzer, professor of coastal sciences at the Asian School of the Environment at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), in Singapore. “And it really is a testament to the way Singapore considers long-term planning in virtually everything it does.”

More than coastal defense

Singaporean officials claim it is a simple sea wall, but they wanted to maintain residents’ access to the coast. The URA plan would create more than 20 kilometers of new waterfront parks, with land also available for residential, recreational and commercial use.

Lee Sze Teck, a consultant with Singapore-based real estate firm Huttons Asia, explained to CNN that Long Island offers the “potential to build between 30,000 and 60,000 homes,” in both low-rise and high-rise buildings.

Land in Singapore, one of the most expensive property markets in the world, is notoriously scarce. Therefore, creating space for housing ensures that the project “can serve the community in many different ways,” says NTU’s Switzer.

And there is another geographic vulnerability that the proposal helps mitigate: water scarcity in Singapore.

Despite its tropical climate and heavy investment in desalination plants, the country has long depended on water (piped across the border from the Johor River in neighboring Malaysia) to meet demand. But given the persistence among Malaysian officials with the decades-old agreement — and with Singapore’s water consumption until 2065 — self-sufficiency is a geopolitical priority.

By connecting to the mainland at each end, Long Island would create a huge new reservoir, trapping freshwater that would otherwise be discharged into the sea. Switzer, who advises government agencies but is not directly involved in the project, believes the proposal could make a “major contribution” to Singapore’s growing water needs.

“The government is looking for as many victories as possible,” he adds. “It’s not just about coastal defense.”

An artist’s impression of the project, produced by Singapore’s urban planning agency using AI tools, shows the project’s potential residential and leisure uses. URA

Prepare the country for the future

Officials say they expect Long Island to take “a few decades” to plan, design and implement. After the land is recovered, it will take years, or even decades, until it is sufficiently stabilized to be able to build on it.

The Singapore government is banking heavily on Long Island as an illustration of its long-term vision — a common theme in the island’s politics. (Singapore’s founding father and prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, famously said: “I don’t calculate in terms of the next election… I calculate in terms of the next generation; in terms of the next 100 years; in terms of eternity.”)

Lee’s eldest son and later Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong, in 2019 that protecting the country against rising sea levels could cost 100 billion Singapore dollars (about 72.5 billion euros) over the next century. Earlier this year, his People’s Action Party — which has won every election since Singapore’s independence in 1965 — highlighted Long Island prominently in its election manifesto, with Lee’s successor, Lawrence Wong, also joining the bill.

Land reclamation has always been a central theme in Singapore’s efforts to prepare for the future. The country’s total area is now 25% larger than when colonialist Sir Stamford Raffles established it as a trading post for the British East India Company in the early 19th century. In fact, the coast on which Long Island will be built was itself reclaimed during the call of the 1960s and 1970s, when almost 15 square kilometers of new land were created, including a long stretch of beach, in the east of the country.

An aerial photograph of Singapore’s East Coast Park, the coastal strip along which the proposed flood defense would be built. Vipula Samarakoon/Alamy Stock Photo

However, land reclamation brings its own political and environmental challenges. The process requires enormous amounts of fill material (Long Island would need 240 million metric tons, according to ), which traditionally consists of imported sand. However, major Southeast Asian exporters — Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia and Vietnam — have at various times banned sand exports, citing environmental concerns over its extraction.

Currently, Singapore is looking for alternatives that reduce dependence on its neighbors. Investigations are underway, for example, to check whether ash from incinerated landfills can be used, together with soil and construction debris.

Nature Society Singapore has, however, raised a number of concerns, including the impact of land reclamation on the region’s horseshoe crabs, hawksbill turtles and Malay rainforest turtles that nest there.

“A much broader picture”

Other low-altitude nations are — or are considering — turning to land reclamation to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Indonesia’s proposal for a gigantic sea wall to protect its capital, Jakarta, remains shrouded in intense political debate more than a decade after the first plans were presented. Thailand and the Maldives are among the other countries that have suggested building islands in response to rising sea levels.

In Denmark, construction of a 110-hectare artificial peninsula intended to protect the capital, Copenhagen, from severe flooding began in 2022, although it continues to be the target of protests.

In contrast, there has been little significant opposition to Singapore’s Long Island thus far. Flood resilience appears to be a priority in a country that has spent (around €1.77 billion) improving its drainage infrastructure since 2011.

The scheme may be the ultimate example of coastal resilience, but NTU’s Switzer thinks the broader strategy could encompass everything from sediment realignment to “nature-based solutions” like building oyster beds or expanding mangroves and offshore reefs.

“Long Island is just one part of a much, much larger picture,” he adds. “As a low-lying nation, incredibly dependent on our coastline, this has to be at the forefront of everyone’s thinking.”