If humanity has been riding horses for millennia, why not do the same with zebras? The question necessarily takes us to the origins of equine domestication and the biological reasons that make zebras practically impossible to domesticate.

To begin with, it is necessary to remember that the human relationship with the horse was not always one of partnership. During prehistory, horses were mainly hunted for food. It was only much later that they began to be domesticated and transformed human mobility forever.

For decades, recalls , the main archaeozoological theory about the domestication of horses was the so-called “Kurgan hypothesis”. In the region of present-day Kazakhstan, where the ancient Botai culture existed, archaeologists found thousands of horse bones dating back to around 4000 BC, accompanied by evidence such as possible fence posts and pottery with traces of fats of equine origin, probably associated with the collection of milk.

The wear identified on the animals’ teeth was initially interpreted as a sign that they were already using brakes. But recent studies have challenged this view.

Similar patterns of tooth wear have been identified elsewhere without any evidence of domestication. Furthermore, in-depth genetic analyzes have adjusted the timing of these events.

A genomic study published in June 2024 in Nature revealed that Yamnaya horses were not direct ancestors of the first domestic horses, known as the DOM2 lineage, nor did they show signs of controlled breeding. Domestication appears to have actually occurred in the Black Sea steppe zone, but later than previously assumed, shortly before the rapid expansion of horses and chariots at the beginning of the second millennium BC.

But if we can domesticate horses, why not zebras?

Difficult and sharp

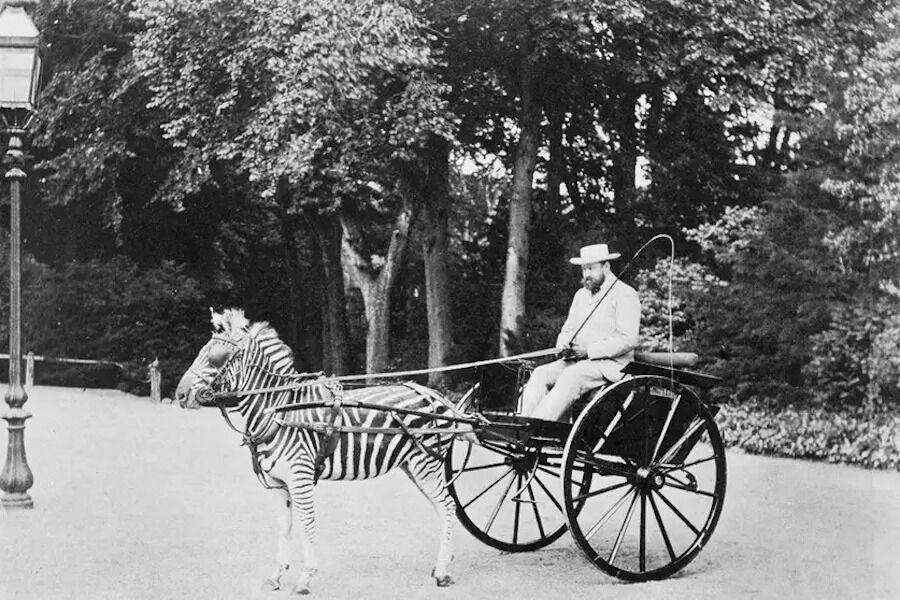

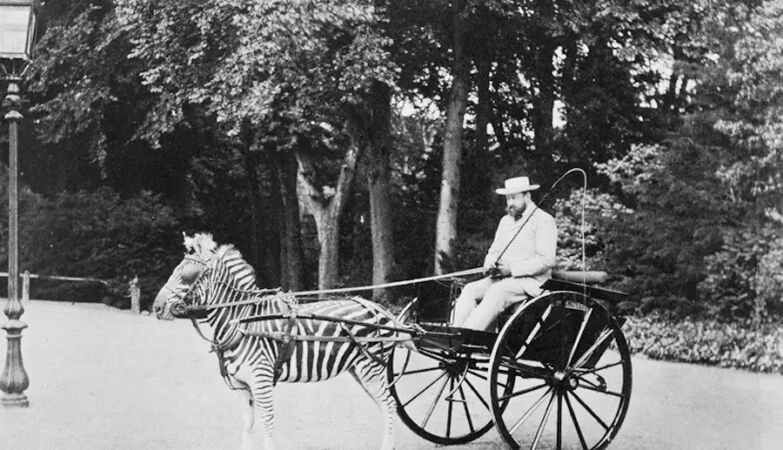

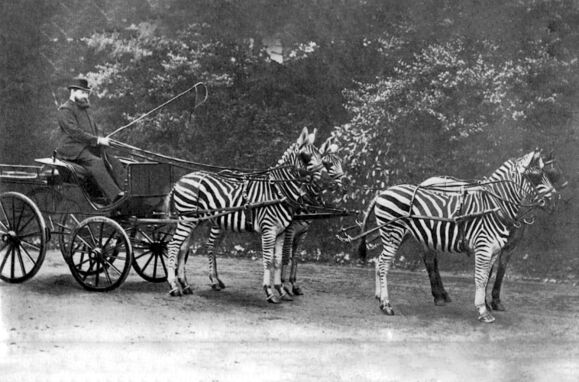

PD

Lord William Rothschild with his zebra-drawn carriage, 1890.

The problem was definitely not a lack of will.

During the colonial period, the Dutch attempted to tame zebras in South Africa, but quickly discovered that these resist fiercely to domestication. Although some dogs can be trained occasionally, most are able to free themselves from harnesses and have an extremely difficult to control temperament.

At first glance, a zebra may just look like a striped horse, but the species split from a common ancestor about 4 to 4.5 million years ago. The adaptation of each one to their respective environments determined very different behaviors.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where lions, cheetahs and hyenas are natural predators, zebras have evolved into animals highly vigilant, reactive and equipped with an extremely keen escape instinct. When cornered, they have a impressive defense capability: A single kick can break a lion’s jaw.

These characteristics make them poor candidates for domestication. Unlike Eurasian equids, whose population was more vulnerable and dependent on humans, zebras have always maintained a strong autonomy and a natural aversion to close contact with people.

Domestication, as a rule, requires species that mature quickly, exhibit a stable temperament and develop a relatively cooperative relationship with humans — attributes absent in zebras.

There are, of course, historical exceptions that feed the myth that it would be possible to ride zebras like horses. The naturalist Walter Rothschild (in the photos) drove, in the Edwardian period, a cart pulled by zebras, and there are reports of isolated cases of zebras being trained to ride. But experts and historians emphasize that these are rare situations that say nothing about the species in general.

Even if it were possible to tame them consistently, there would be another obstacle: the size. Zebras are considerably smaller than most modern horse breeds, closer to ponies, which would limit their ability to support riders or carry larger loads.