Youtube

The enigma surrounding the supposed Babylonian battery continues to intrigue archaeologists and the curious. Especially after she mysteriously disappeared without a trace and was never seen again…

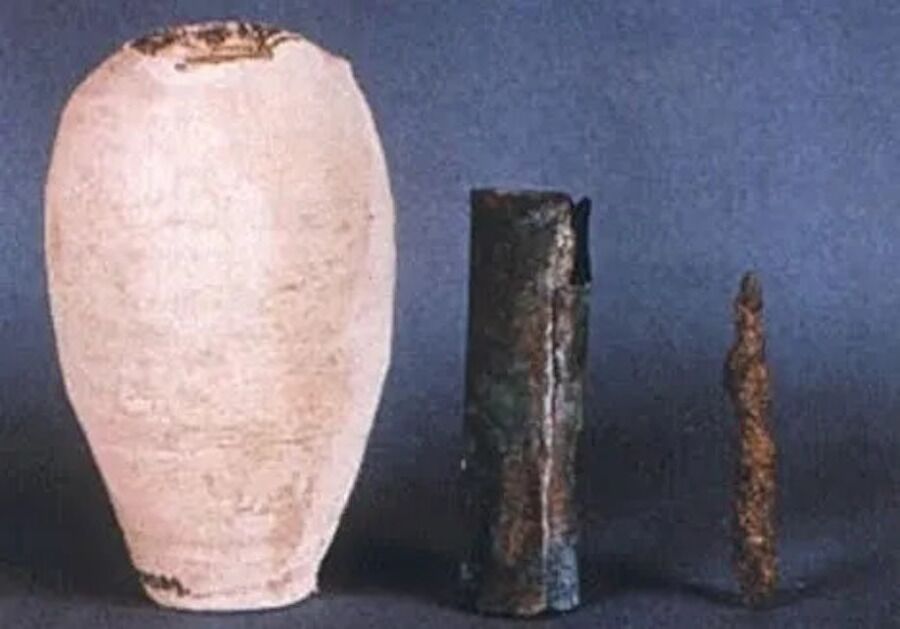

Discovered in (also) strange circumstances, at the beginning of the 20th century, a small set of artefacts consisting of a clay jar, a copper cylinder and an iron rod are the pieces of a puzzle that no one has been able to put together to this day.

It is one of the most debated enigmas in Near Eastern archaeology. Known as the “Battery of Baghdad”, the object has attracted all attention since it was Wilhelm Kinga German artist and archaeologist who would later direct the National Museum of Iraq, suggested that it could be a rudimentary form of galvanic cell, created many centuries before Alessandro Volta.

The piece was found in the Khujut Rabu area, near the ruins of the ancient city of Ctesiphon, successive capital of the Parthian and Sasanian empires. The jar, measuring about 14 cm when recovered, originally had a lid sealed with bitumen. Inside was a copper cylinder, inside which was fitted an iron rod that, apparently, would go through the top of the container.

The chronology proposed by König pointed to the Parthian period (150 BC–223 AD), but studies later leaned towards a Sasanian dating, between 224 and 650 dC Whatever the exact period, the antiquity of the object is indisputable and long predates the first formal description of a battery, published by Volta in 1800.

König presented his thesis in 1938, in the German magazine Research and Progress, in an article entitled “A galvanic element of the Parthian period?”, according to . Without ancient texts describing anything similar, the archaeologist relied on material analysis: two metals with different electrochemical potentials, copper and iron, and evidence that the jar may have contained an acidic liquid, such as vinegar or wine.

Modern trials have shown that with a suitable electrolyte, the set can generate approximately one volt. In theory, with multiple units connected together, the voltage could increase.

From here a building of hypotheses rose. What could a battery created almost two thousand years ago have been used for? One of the proposals concerns the medicineinspired by practices known from Antiquity (the Greeks, for example, used electric fish to relieve pain). Another suggestion is to special effects in templessuch as statues that would produce small shocks to impress worshipers (the idea was tested in a 2005 television documentary).

The hypothesis defended by König himself was that of electrogalvanization: applying a thin layer of metal to objects, a simpler and more precise method than the techniques then in use. The problem is that none of these interpretations withstands critical analysis.

The intensity generated would be too low for any gilding process. There are no traces of wires, nor evidence that Parthian or Sasanian civilizations mastered electrical principles. Furthermore, the supposed electrolyte would have to be renewed frequently, something difficult in a container sealed with bitumen. And, above all, there is a lack of any written reference or material that confirms the use of similar devices — something strange to say the least, if it were such an innovative technology.

An answer ahead of everyone?

Faced with these obstacles, an alternative explanation has gained popularity over the last few decades: that the set was a container for storing manuscripts. Very similar jars were found in nearby excavations, used to preserve scrolls wrapped around sticks or cylinders. The shape of the piece itself, as well as the archaeological context, seems to fit better into this scenario. Interestingly, König himself mentioned this type of container in his article, although he did not consider that the example he had in his hands could serve precisely this function.

In 1996, specialist Gerhard Eggert summarized this view in Skeptoid Magazine, arguing that the “ritual or functional” explanation, linked to the storage of texts, is much more plausible than interpreting the object as a source of energy. According to Eggert, the idea of an ancient battery results more from an impulse of “scientific mysticification” than from solid evidence, violating the principle of Occam’s razor — the requirement to prefer simple hypotheses when they adequately explain the facts.

The debate gained an additional dimension with a new mystery. In 2003, during the looting of the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, the artifact disappeared without a trace. Since then, it is not known where it is or what state it is in, making more complete analyzes that would allow us to definitively clarify its nature.