Young activists in US high schools had the FBI on their backs at the behest… of their own parents. It happened in the 60s and hundreds of cases are only now coming to light.

New documents, recently declassified, reveal that, during the 1960s and 1970s, dozens of American parents turned to the FBI, and, in some cases, actively collaborated with the agency to watch your own children teenagers involved in student movements and political protests in secondary schools.

One of the cases brought to light is that of Laura Mackay Irwinformer FBI stenographer, in Charlotte, North Carolina. In March 1969, alarmed by her 17-year-old son Basil Jr.’s involvement in the newly created Charlotte Student Union, Irwin wrote a letter to then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The student group demanded a more relevant curriculum and greater participation in school decisions, which for Irwin already seemed a sign of something more dangerous.

In the letter, he maintained that teenagers were not prepared to face “groups that operate in universities and try to destroy our educational system” and warned that these influences were “reaching high schools”.

Convinced that older young radicals were manipulating students, the ‘mother hen’ suggested that the FBI send agents to schools to warn students about the “danger of communism”considering the FBI to be the entity best suited to help.

Hoover responded a week later, thanked them for their concern and assured that they understood the “problems” students face today. He forwarded the letter to the FBI office in Charlotte with a clear instruction: develop Irwin “as a potential security briefer.”

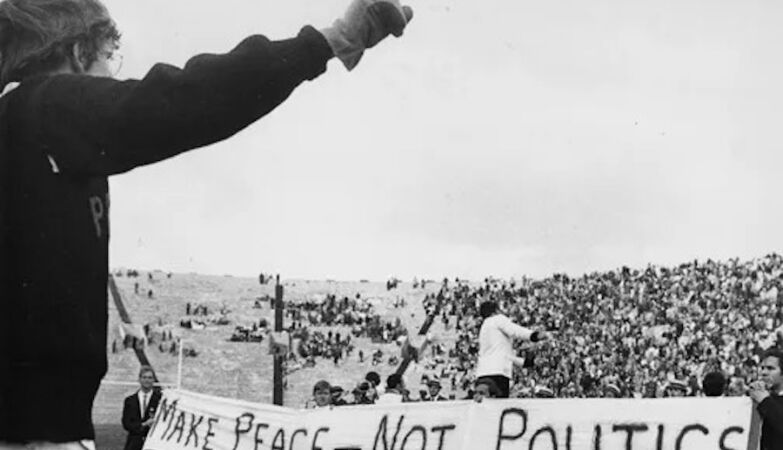

Inspired by the civil rights movement, the fight against the Vietnam War and currents such as Black Power, the Chicano movement and emerging feminism, thousands of teenagers began to organize themselves into autonomous groups. They fought for freedom of expression in schools, for curricular reforms and against the repression of political opinions in high schools. These struggles took the form of strikes, boycotts, sit-ins, marches, petitions and lawsuits.

Many adults, particularly among the white middle and upper-middle class, saw this activism as threat and disorder.

The press amplified the alarm: in 1969, the New York Times spoke of a “disturbing increase” in unrest in high schools; the following year, the Los Angeles Times reported a “frightening rise” in race riots in high schools. As the image of high schools in rebellion spread, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies mounted surveillance campaigns specifically targeting high school students.

Going directly to the FBI was common among worried parents. Many student groups, in fact, sought logistical support from older activists but, as former youth activist John Eklund recalls, there was nothing “nefarious” about this: young people were grateful to be taken seriously by supportive adults.

Since 2014, the researcher has filed nearly 2,000 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to access records about FBI surveillance operations targeting high school students in cities, suburbs and rural areas. He obtained 233 documents, many of them unpublished until then and whose declassification took between two and six years; In some cases, applications have remained pending for a decade.

In addition to collecting information, the FBI sought to intervene directly in family dynamics to curb youth activism. Between 1968 and 1970, under the COINTELPRO counterintelligence program, the agency specifically targeted high school students.

In a December 1968 case, after the arrest of a 17-year-old girl at a demonstration against the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington, officers noticed the obscenity-filled anti-war message written on her cap, which also mentioned the New York High School Student Union. An anonymous letter was then sent to the young woman’s mother, supposedly written by another “concerned father”, warning that if she allowed her daughter to continue with her “yippie” friends, she would end up “under psychiatric care”.

It is not known how the family reacted to the threat, but later documents show that the tactic of anonymous letters and phone calls to parents continued to be suggested to undermine student activism.

In total, the records analyzed indicate that the FBI monitored at least 109 independent groups of high school students, 60 underground school newspapers and 200 protests or incidents of violence on campuses between 1961 and 1976. The agency itself admits that these numbers are probably lower than reality, according to the Smithsonian.

The parents were not the only ones to collaborate with the FBI. School principals, teachers, classmates, and anonymous citizens also handed over confiscated pamphlets, meeting summaries, and lists of names. The difference is that, while many of these collaborators saw young people as mere pawns or nuisances, parents believed they were defending their children’s innocence.