90 years ago, a left-wing movement broke out in Brazilian barracks involving military personnel and civilians dissatisfied with the federal government. The objective was to forcibly remove the president from office and establish a socialist government along the lines of the Soviet Union (USSR).

There were shootings and deaths in large cities such as Natal, Recife and Rio de Janeiro, then the federal capital. The barracks, called by the press at the time, was defeated and failed within a few days, but it paved Vargas’ path towards dictatorial power.

The mutiny that involved military members of the lieutenant movement and trade unionists also sealed the image of a communist threat — widespread to this day in sectors of the right —, whose permanent objective would be to end order, peace and destabilize the direction of the nation.

“Although promptly crushed, the communist insurrection of 1935 left deep trauma in Brazilian political memory”, says historian Homero de Oliveira Costa in the book “A Insurreição Comunista de 1935”.

In the work, the author analyzes the political, military and social objectives of the attempt organized by the ANL (Aliança Nacional Libertadora) —a broad front that involved communists, socialists and democrats against fascism— and led by.

Political scientist Paulo Ribeiro da Cunha, professor at Unesp (Universidade Estadual Paulista) and author of “Militaries and Militancies”, states that the anti-communist discourse preached by current politicians and military sectors is a legacy of the times of the Empire, “but it reached heights after the 1935 uprising”.

“After the 1917 Revolution in Russia, anti-communism gained a much greater dimension and the discourse of fear became stronger. It was even one of the justifications for the 1964 military coup”, says Cunha.

In addition to the violent reaction of the Vargas government to repress the mutineers in Rio de Janeiro, Natal and Recife – the main locations of the insurrection – the 1935 attempt failed due to a lack of planning, as the movement’s leaders themselves recognized.

Supported by the Communist International, which saw Brazil as fertile ground for the expansion of socialism in the world, the objective of Prestes and the ANL was to prepare the country for the overthrow of the regime and the rise of a popular government, but with strategy, organization and, preferably, without bloodshed.

On November 23, a Saturday, events in Rio Grande do Norte precipitated the events. In the barracks of the 21st Battalion of Hunters, in Natal, a group of low-ranking soldiers led by sergeant-musician Quintino Clementino de Barros rounded up the officers on duty and ordered: “You gentlemen are arrested in the name of Captain Luiz Carlos Prestes”.

There was no resistance. From then on, the insurgents, led by Quintino and supported by organized civilian groups (such as the dockers’ union), took over the barracks and occupied strategic locations: the government palace, Vila Cincinato (official residence of the governor), the railway station and the electricity, telephone and telegraph centers.

Informed about the riots that were spreading throughout the city, Rio Grande do Norte governor Rafael Fernandes and other civil and military authorities fled and hid in the homes of allies.

For three days, the city was under the control of the rebels, who issued a decree removing the governor, founded a newspaper called “A Liberdade”, proclaimed a revolutionary-communist government and took populist measures: free trams, confiscation of food in the markets, forced withdrawals at the local Banco do Brasil branch and distribution of money to the population.

After the action of local legalist forces, with federal support, the rebels fled to the interior and Governor Fernandes was returned to office.

“It was the first, only and fleeting Soviet government in the history of Brazil”, records historian Helio Silva in the book “1935 – A Revolta Vermelha”, about the events in Natal.

The events were also recorded by the writer, historian and folklorist Câmara Cascudo (1898-1986), who was born and lived practically his entire life in Natal. “Without systematic direction, the authorities were hidden, the people were terrified, Natal was an easy prey”, he wrote, about the “communist government”.

The events in Natal were rushed in such a way that there was no time to notify the ANL command in Rio de Janeiro, whose leaders were planning the best moment to break out the revolution at a national level. “It was a surprise for me,” Prestes would say later.

On Sunday, November 24, it was Recife’s turn, where the insurrection also began in the local Caçadores Battalion and soon spread to the capital of Pernambuco and Olinda. There was a shootout lasting several hours between rebels and loyalist troops, which resulted in deaths on both sides and a retreat by the communists, ending the riot.

In Rio de Janeiro, the uprising arrived on November 27th, under the command of officer Agildo Barata, linked to the communist party and assigned to the 3rd Infantry Regiment, in Praia Vermelha. Alerted by the events taking place in the north of the country, the legalist forces under the command of General Eurico Gaspar Dutra, commander of the 1st Army, acted quickly.

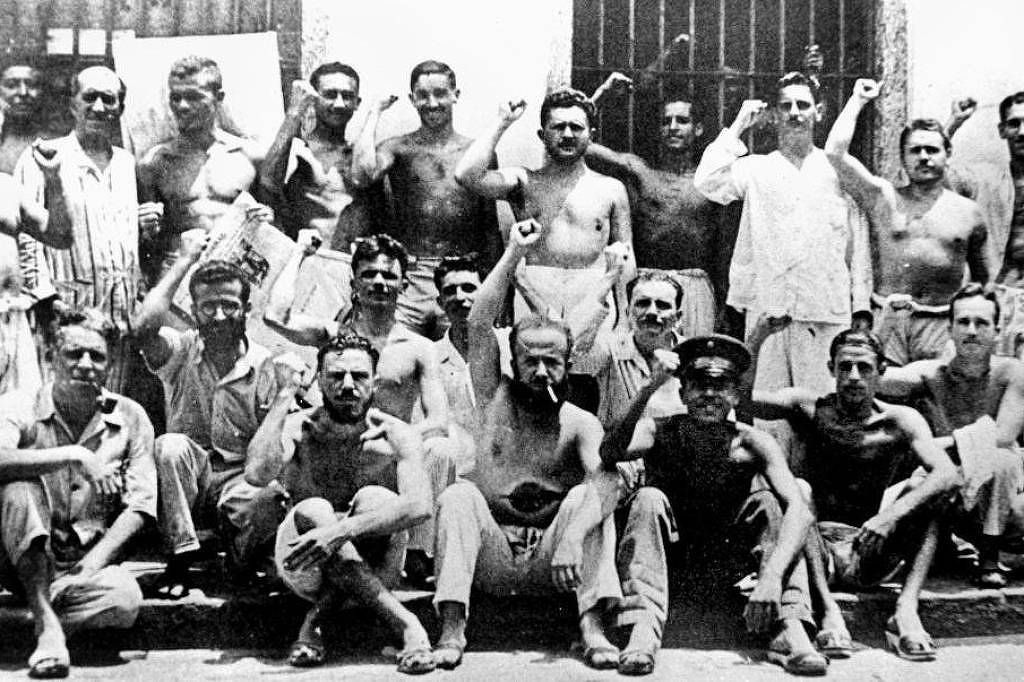

The movement was violently suppressed just hours after the first shootings that took place in the federal capital. The official number of deaths, as occurred in the Northeast, was never accurately counted.

It was the end of the Communist Intentona and the beginning of a time of persecution and arrests of left-wing activists by the federal government across the country, including the writer Graciliano Ramos. Because of what he treated as a communist threat, President Vargas managed to establish, without major political difficulties, the dictatorship of the Estado Novo, in 1937.