Discusses one of the most relevant topics since the creation of . The Draghi report and the study by the London School of Economics have put back at the center of the agenda a question that should be simple, but which rarely receives clear answers: what needs to be done for the continent to return to sustainable growth? From this, something new was formed: movements in search of a long-term consensus, capable of surviving governments, guiding strategic investments and maintaining cohesion between countries.

The European diagnosis is clearly that, without growth, there is no way to finance the energy transition, the defense of the continent, deal with population aging and guarantee technological autonomy in a more competitive world. Everything involves productivity and innovation, integration of industrial standards and institutional security. The region chose to discuss a new project; If it is going to prosper, the story will have to tell.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Brazil remains trapped in shallow debates. Since the Washington Consensus, whose principles inspired monetary stabilization, we have lacked a minimum set of priorities to guide policies and provide predictability to business. And, mainly, engaging society in the challenge of growing more and sustainably, with continuous improvement in social well-being.

Our problem is known and measurable. Brazilian productivity has been stagnant for four decades and, since 2010, according to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), the country’s potential growth has steadily slowed down, reflecting limitations in technology, education and efficiency. The investment rate remains around 18% of GDP, a level insufficient to support deeper economic modernization.

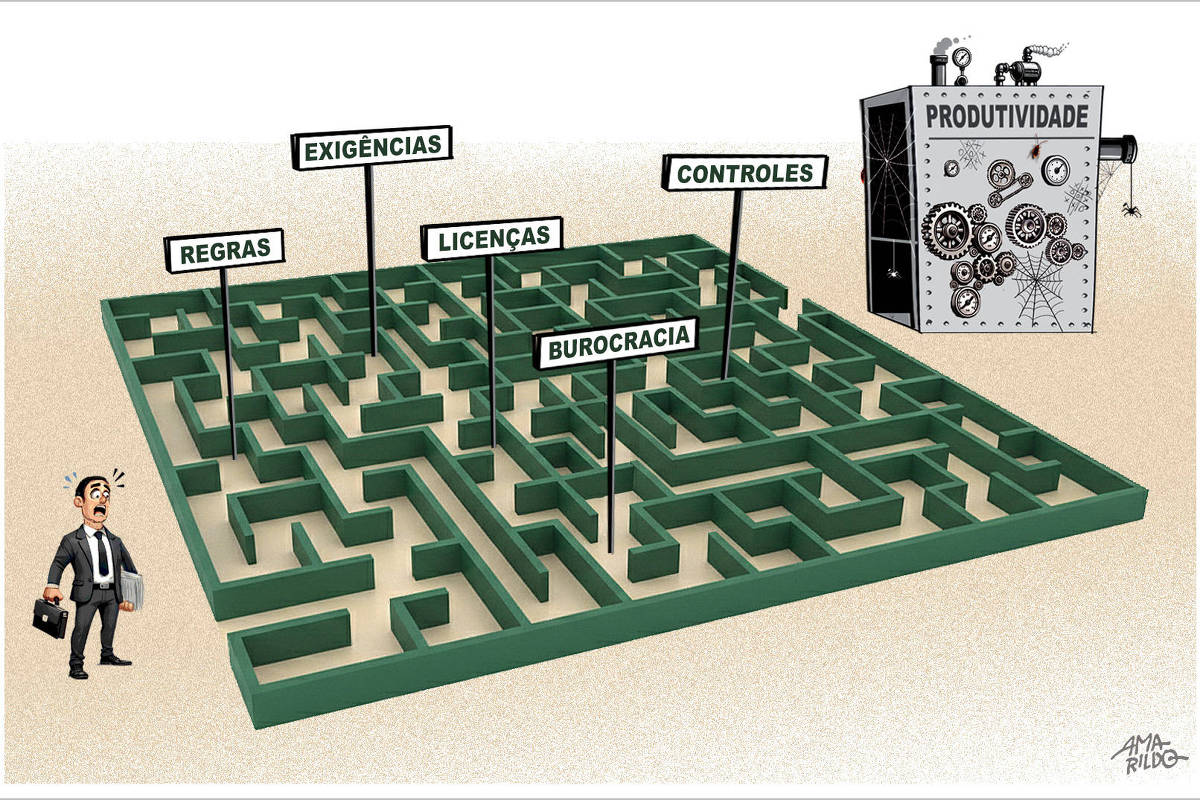

There are also well-known challenges: in a country where rules, bureaucracy and litigation abound, there is a lack of predictability in the business environment, learning and innovation. Too much consumption, not always responsible; there is a lack of savings and efficient allocation of scarce resources.

At the same time, Brazil has real opportunities: clean energy, efficient agribusiness, environmental assets of great value, availability of natural resources that are becoming increasingly scarce on the planet. We have public digital infrastructure like few other countries, with great scale and quality: Pix (5 billion monthly transactions), e-Social (more than 80 million active links), Cadastro Único (39% of the population) and digital identity (more than 150 million). The SUS reaches at least 160 million Brazilians. International studies show that digitalization and interoperability can reduce the administrative cost of public services by up to 30%. For Brazil, where the “regulatory cost” is estimated at around 1.5% of GDP, the potential gains would be significant. A State capable of providing secure, standardized and auditable data reduces friction, deviations, reduces the cost of serving and improves the quality of public policies.

But what we lack, until now, is not diagnosis; it is consensus.

The European discussion highlights that sustainable growth is not born from isolated initiatives, but from mobilizing projects, anchored in principles that cut across governments. Draghi and LSE converge on three essential pillars: 1) institutional and regulatory stability; 2) continuous productivity, technology and innovation agenda; 3) strategic investments with solid governance — one focus would be the defense area.

None of this happens spontaneously. These are political choices, based on institutional maturity and financing capacity, articulated by leaders committed to a vision of the future.

Brazil needs to build a similar movement. This requires defining a minimum core of national objectives, recognized by society as indispensable, with clear metrics: increasing productivity; increase predictability in the business environment; simplify regulations and reduce the cost of investing; modernize the State; qualify the workforce for a digital economy; and deepen our insertion in international trade. Update the design of programs based on social dynamics, especially demography, deepening public security policies.

Countries that have overcome the middle-income trap have done so with continuity, clarity of priorities, lasting institutional commitments and evaluation of results. There is no other way. Without this type of convergence, politics is reduced to disputes over means, while the country continues without discussing ends.

Society — workers, companies, academia, governments — needs to return to the center of this debate. Brazil has already built important consensus to combat inflation, which in its worst moments seemed to be an unsolvable problem. It is possible to construct guidelines to develop the country.

Growth requires a consistent institutional agenda, capable of reducing uncertainty, bringing back fiscal balance, increasing productivity, attracting powers and institutions, and reconnecting Brazil to the future. And make young people’s eyes shine when they look at their opportunities and their own country.

Growth means making choices and building consensus to move forward. If we don’t realize this, we will continue to alternate occasional advances with frequent setbacks, while wasting historic opportunities.

You need to have a sense of urgency to progress.

LINK PRESENT: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click the blue F below.