Alberto, 48, was taken aback a few weeks ago. When he opened the computer of his daughter Paula, 12, a student at a public high school in the center of Valencia, he saw that the girl had asked Google’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) to give her a summary of a story by Oscar Wilde that he knew she had to read for language class. And, in addition, he gave the main characters, and questions like those that could appear on a first-year ESO exam. Alberto questioned his daughter, and she assured him that she had read the story more than a month ago, that she had the exam the next day, and that, since she had left the book at school, she had looked for it to review. “I accepted her explanation because she is a very good student, but the truth is that I was worried. It may sound naive, but I hadn’t seen it coming,” he comments.

Scenes like the one described by Alberto (whose name and that of his daughter have been changed to protect the minor) are repeated in thousands of Spanish homes, says María Sánchez, president of Ceapa, the large confederation of public education families, which brings together more than 12,000 associations of mothers and fathers of students (Ampas) from schools and institutes. Starting with his own home, he says. Children, at the end of primary school, and especially adolescents, have started using AI at home to study without supervision from teachers or parents, in a way that sometimes consists of productive help and many others in an externalization of intellectual effort. A change in which families do not know how to act. “Mothers and fathers convey concern to us, because the majority do not have, or rather, we do not have, sufficient knowledge to guide them or control their use. Some do not even know what,” says Sánchez. In response to that concern, your entity has just completed a guide, which will be presented in December, that tries to guide parents and children about the risks and educational opportunities of new technology.

In recent months, various surveys have been published, of uneven quality and with differences in age ranges, on how much the use of AI to study has spread among students, which show figures ranging from more than 40% to more than 80%. The most recent official data, published on November 20 by the INE, indicates that 59% of the population between 16 and 24 years old already uses it for this purpose.

Directly to the kids

One of the main problems with the school use of AI in children and adolescents, points out the president of Ceapa, is that its rapid expansion is not responding to a plan designed by educational administrations to improve the learning of minors. But rather a race of private companies, “driven by economic interest”, that have not gone knocking on the door of teaching departments, educational centers, teachers or parents, but directly to the end user, the students, who in Spain alone, between primary and secondary, number six million. “It is happening to us,” says Sánchez.

The issue generates concern and also “controversy” in Affac, the largest entity of Catalan families ―which is not part of the state-owned Ceapa and brings together another 2,400 Ampas―, admits its director, Lidón Gasull. “In my opinion it is not about opposing Artificial Intelligence, but about setting limits, regulating, and being very careful, because we are talking about a particularly vulnerable population, and we have no information or control over the real impact that its use can have on their learning process. But on these issues the administration is always far behind reality,” he says. Until last December, the Government did not publish a report of recommendations on the use of screens in educational centers and social networks in minors, and at the moment, the Spanish educational administrations do not have a regulation of AI in educational matters, although Galicia is preparing regulations (aimed primarily at use in the classroom) and the Ministry of Education plans to address the issue in the future together with the Ministry of Digital Transformation.

One of the main arguments in favor of the professional use of AI is that it allows us to free up time from less relevant tasks to dedicate it to truly important ones. The same reasoning seems applicable, to some extent, to higher education students. In primary and secondary school, on the other hand, the tasks are designed – or should be – so that kids acquire knowledge and skills during the process of doing them, so that productive savings generally predicated on AI is much less evident.

Flashcards, maps and podcasts that help you study

Leaving aside, which seems like a lot – from helping them with cumbersome administrative tasks to assisting them in the early detection of students with learning difficulties – that fall within the professional use of AI, experts point out that kids can use it in two very different ways. Asking them to do the assignments or read the books for them, which will probably end up having harmful cognitive consequences, and will also be negative for their grades, since, as artificial intelligence spreads, it is foreseeable that the forms of evaluation will also change to become more face-to-face. Or, using it with an active approach, which involves applying techniques that science has shown work when learning.

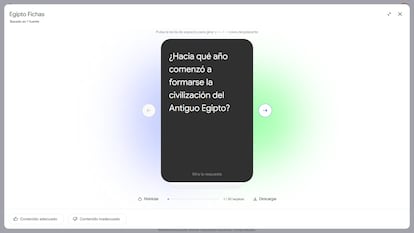

This second type of positive use is what Ben Gomes, Google’s Director of Learning and Sustainability, highlights in an office at the Google DeepMind headquarters in London, at the end of a forum on AI applied to learning organized in mid-November to which the American company invited EL PAÍS to attend. For example: enter a document, say a History topic, into the AI application and ask it to create flashcards (cards with questions and answers in the style of Trivial) or questionnaires, two of the classic ways of exercising evocation (rescuing what has been learned from memory), which, . Or also, ask create mind maps with said content, or even a podcast with the topic, so that the student can listen to it, for example, while walking or playing sports. Apps like NotebookLM, ChatGPT or Le Chat allow some or all of those things.

With or without parental control

The companies that are focusing on educational AI have among their priorities, Gomes continues, the so-called “guided learning”, applications (or utilities within those that already exist) that adopt “a more Socratic style of interaction, with more visual elements, and questions at the end, which does not give the student the answer directly, but rather makes them make a little effort first.” The Google manager assures that his company has decided not to implement in its guided learning system (Gemini) any type of parental (or teacher) control that prevents the application from giving students the resolution of the exercise, but only clues and examples of how to do it, to prevent them from “getting frustrated” and stopping using the application (and perhaps, although he did not say this, they go to the competition).

The idea of AI as a mentor for students without a parental pin has, however, a starting obstacle, warns Dennis Mizne, general director of the Lemann Foundation, a non-profit entity that offers educational support to more than 600,000 Brazilian students per month. “The question is: Who said that students want a tutor or a private teacher? Because, in practice, the big problem we see when applying many educational technologies is the very low commitment of students. The vast majority do not constantly look for ways to learn more, nor do they have a high intrinsic motivation. Those who do are, in fact, the exception.”

Mizne, who trained at the universities of Sao Paulo, and later went to Columbia and Yale, believes that the type of students who are highly motivated to learn more are, as adults, overrepresented in the leading companies that are developing educational AI, and that leads them to think that the majority of students will take advantage of the opportunity to have a personal tutor. “But it is not like that. Most will not ask the chatbot to explain something to them, or help them understand it step by step. What they will do is try to speed up the process. Tell them: Do my homework, write my essay, solve this exercise… And that is not going to generate better educated and prepared children.”

School resistance

Mizne, like the presidents of the Spanish Ampas confederations, therefore believes that governments should regulate educational AI applications, and that these should be developed by education experts, including school directors, teachers, and also families. To reduce the risks that accompany these applications, and also to ensure that it adapts to the school, an institution that has proven capable of successfully resisting the incorporation of other technologies that at the time also seemed destined to revolutionize teaching, such as personal computers, the Internet and mobile devices.

The applications of artificial intelligence in education pose, on the other hand, a risk of a very different nature, points out the professor of Political Science at the University of California, San Diego, Agustina Paglayán, author of Raised to Obey: The Rise and Spread of Mass Education (Raised to obey: the rise and expansion of mass education, published this year in the US, without translation into Spanish). Paglayán shows in his research that the creation of mass educational systems, especially throughout the 19th century, of which the current ones are direct heirs, did not respond to “democratic ideals, industrialization, nor the goal of promoting knowledge or eradicating poverty”, but were implemented with “a political objective of forming obedient citizens as part of a broader project of formation and consolidation of the national State.” Prussia began doing it in the 18th century, and the rest of the European, American, Asian and African countries followed throughout the following centuries. The tools that the State has historically had when it comes to indoctrination – in the sense of teaching someone to accept a set of beliefs without questioning them, regardless of the content of said ideas – were, however, much more limited than what AI now draws, the professor points out.

powerful actors

The means that governments have had until now have basically been textbooks and their ability to influence the training and hiring of teachers. But these have always retained, to a greater or lesser extent, a certain degree of autonomy, says Paglayán, they have never been a carbon copy of what the State wanted them to be. “Even in authoritarian systems, teachers have often questioned textbooks, exposing students to different perspectives. AI gives them, instead, a much more direct tool to reach students, with a software that not only exposes the student to a certain set of beliefs but, if the student asks questions questioning them, over and over again he can reiterate and emphasize them.” The potential danger of reduction of critical thinking, Paglayán adds, now does not come only from the States, but from .

Those interviewed for this article agree that the students must. It is, they point out, a technology with great capacity to both enhance learning and undermine it, and if the school simply turns its back on it, another gap will open between those whose families can guide them and those who cannot. While it is possible or not to approve a regulation based on what most benefits children and adolescents, Rebecca Winthrop, director of the Center for Universal Education at the American Brookings Institution – who, like Dennis Mizne and Agustina Paglayán, participated in the forum on AI organized by Google – proposes adopting a “minimalist use of AI.” A decalogue that opts for non-digital solutions. To opt, if they are useful, for less invasive technologies. And to take into account, when choosing between various options, those that involve less cost and less environmental impact, an area in which AI has a lot of room for improvement.