M. López-García, M. Díaz-Andreu

Photographs of Neolithic cowrie shells from Catalonia that still produce sound today — like trumpets

In a new study, a team of archaeologists experimented with playing six-thousand-year-old cowrie shells from Neolithic Catalonia, and showed that these “trumpets” were highly effective for communicating over long distances — and could also have been used as musical instruments.

In different parts of the world, buzios were used to produce sound. THE Cataloniawhere several cowrie shells dating back six to seven thousand years were found, is one such example. However, unlike specimens from other regions, these have received little scientific attention.

In a new one, published this Tuesday in Antiquityresearchers from the University of Barcelona analyzed cowrie shells discovered in Neolithic settlements and mines in Catalonia, and concluded that they produce a sound similar to a trumpet.

“It was known that several specimens of Charonia lampas in a relatively restricted area of Catalonia, specifically, in the lower course of the Llobregat river and in the pre-coastal depression of the Penedès, east of Barcelona”, he explains Margarita Díaz-Andreuresearcher at the University of Barcelona and co-author of the study.

“Their apices were removedwhich led some researchers to suggest that they could have served as musical instruments”, adds the archaeologist, quoted by .

M. López-García, M. Díaz-Andreu

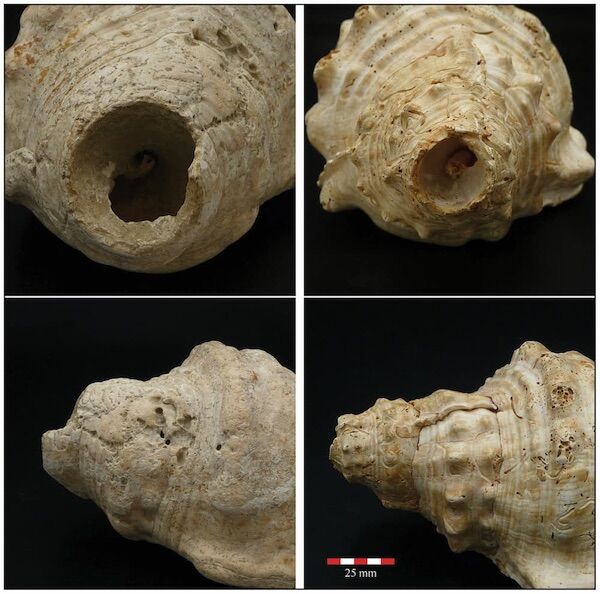

Details of the apical cut of cowries 355-1-51, from Mas d’en Boixos (left) and 408-24, from Minas de Gavà (right)

Analysis of the whelks indicates that they were collected after deaththat is, they would not have been caught for consumption, reinforcing the idea that they were chosen exclusively for its sonic capabilities.

To test this hypothesis, Professor Díaz-Andreu, and Miquel López-Garcíaalso a researcher at the University of Barcelona, analyzed cowrie shells and, for the first time, evaluated their acoustic properties.

In addition to being an archaeologistLópez-García is also a professional trumpet player, which allowed testing not only the ability of whelks to communicate over long distances, but also its potential as a musical instruments.

“Buzios can produce loud sounds and would have been extremely effective for communication over long distances”says López-García.

“However, are also capable of producing melodies through tone modulation, so we cannot exclude the possibility that they were used as musical instruments, with expressive intent”, adds the archaeologist, who personally experienced playing the Neolithic instrument.

“It’s incredible how you can such a characteristic timbre from such a simple instrument, which is nothing more than a slightly modified animal body”, says López-García to . “I think that the closest instrument in terms of timbre today is the horn.”

It is important to note that this densely populated region of Catalonia was mainly shaped by Neolithic agricultural activities.

Whelks were found in villages separated by tens of kilometers, which suggests that they had a relevant role in communication and coordination within and between communities.

It is likely that they have supported activities in agricultural fields surrounding areas and also in the mines near Gavà, where it was extracted variscite, a valuable mineral used to produce beads and pendants, widely traded as signs of prestige.

These findings thus indicate that cowrie shells were much more than simple sound-producing instruments; played an active role in shaping the spatial dynamicsmore economic and social aspects of Neolithic communities, bringing people together through sound communication and, perhaps, music.

“Our study reveals that Neolithic people used cowrie shells not only as musical instruments, but also as powerful communication tools, which redefines our understanding of soundspace and social connection in the first prehistoric communities”, concludes Díaz-Andreu.