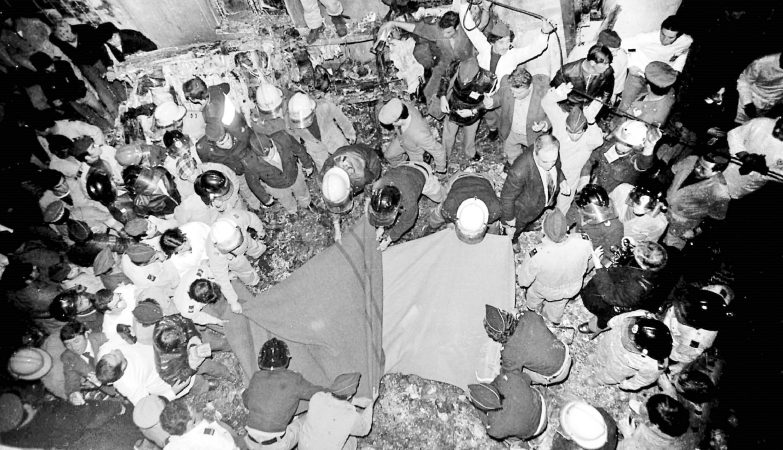

Alfredo Cunha / Lusa

Crash of the Cessna plane carrying Sá Carneiro and Amaro da Costa in Camarate, December 4, 1980

The first investigations into the crash of the Cessna 421 that killed Sá Carneiro and Amaro da Costa concluded that it was an accident. Several parliamentary committees and two confessions clearly point to an attack — which robbed a consolidating country of its charismatic prime minister.

Forty-five years after the night of December 4, 1980, the Camarate tragedy remains one of the darkest and most ambiguous pages in the history of Portuguese democracy.

That day, at 8:24 pm, a Cessna 421 serving the general’s presidential campaign Soares Carneiro crashed over the Fontaínhas neighborhood, a few seconds after taking off from Portela heading to Porto.

On board were the then Prime Minister, Francisco Sá Carneiroyour companion, Abecassis sleepthe Minister of Defense Adelino Amaro da Costa and the woman, the chief of staff António Patrício Gouveia and the two pilots, Jorge Albuquerque and Alfredo de Sousa. There were no survivors.

It is estimated that the impact on the ground occurred approximately 26 seconds after take-off. The plane hit low voltage cablesit lost support and ended up falling onto a house, causing a fire that destroyed several houses and cars, without causing any fatalities on the ground.

That night, the journalist Raul Durão opened the RTP news program with the news of Francisco Sá Carneiro’s death and the first images of the scene of the tragedy, which showed, without filters, the destroyed plane and charred bodies — images that marked a generation.

The tragedy left in shock a country still consolidating the regime that emerged from the 25th of April: the head of the Government and the Minister of Defense disappearedin the middle of the presidential campaign and in a climate of strong political tension.

The investigation began that nightunder the coordination of the Public Ministry and the Judiciary Police. The first investigation, concluded in 1981, found no evidence of crime and pointed to an accident on take-off. In 1983, the Attorney General suspended the investigation.

Over the following decades, however, the case never stopped returning to the political and media agenda. were created ten parliamentary committees of inquiry, something unprecedented in Portuguese democratic life.

Several of these surveys supported the possibility of sabotage. The III Commission, in 1987, concluded that “the plane crashed due to sabotage and, therefore, of an attack”.

The judicial course of the case was marked by successive filings and by absence of convictionsand the case prescribed in 2006without the courts having considered there to be sufficient evidence of a crime, despite new allegations emerging at the time — including that of Jose Estevesa former security agent who claimed to have placed an explosive device on board.

The intention, said the former CDS security agent, was that the device, a fire bomb made with potassium chloride, sugar and sulfuric acid, would cause a fire before takeoffallowing occupants to exit safely, but giving a “scare” to Soares Carneiro — who would lose to Mário Soares, in the 2nd round, the closest presidential contest ever.

Over the years, they have been several theories pointed out about the motives for the attack — most of which maintain that the target would not be Sá Carneiro: the prime minister would have been “collateral damage”.

Em 2001, Ricardo Sá Fernandeslawyer for the victims’ families, published a book in which he argues that the assassination target would have been the then newly appointed Minister of Defense, Adelino Amaro da Costa, a civilian, due to his knowledge of arms agreements with Iran.

In a book published in 2010, the journalist Celia Pedroso than in previous weeks, Amaro da Costa had received “pressure and death threats by telephone”, having shown “concern and a pronounced change of attitude” — and request to carry weapons.

According to the journalist, the then Minister of Defense was “interfering in a series of sensitive issues” related to an alleged “blue bag” and investigating the disappearance of large sums from the Military Defense Fund of Ultramar created by Salazar, which after April 25th had passed under the jurisdiction of the Council of the Revolution.

Em 2012, José Ribeiro e Castro advocated the opening of a tenth parliamentary inquiry, in part due to the confession of one of the alleged conspirators, Fernando Farinha Simõeswho in 2011 had published an 18-page confession online describing his alleged involvement in the operation.

Farinha Simões claimed to have been responsible for conducting the operationat a cost of 750 thousand dollars, for US intelligence agency CIAand that 200 thousand dollars had been given to José Esteves for his bomb manufacturing services.

In 2013, the X Parliamentary Commission of inquiry into Camarate would reaffirm the thesis of sabotage and the point out “gaps” in the performance of the Judiciary Police and the Attorney General’s Office, concluding that the crash of the Cessna 421 “was due to an attack”.

At the end of his audition, José Esteves was victim of stalking of the Judiciary Police from the moment he began to publicly defend that the Camarate tragedy had been an attack.

“Camarate was this, an attack covered up by the Judiciary Policea criminal and stubborn police force because they covered up and never responded for all the crimes they have committed”, stated the former security agent, who despite having confessed to being responsible for an attack, was never tried or convicted.

The Camarate tragedy left a wound in Portuguese democracy, and, forty-five years later, the case remains shrouded in ambiguity, between the memory of the tragedy and the suspicion of an attack.

Every year, at the Prazeres cemetery, in Lisbon, and in various party and state initiatives, the figure of Sá Carneiro is evokedthe man who said that “politics without risk is boring, but without ethics it is a shame” — an idea that some of his assumed political heirs often remember but many others forget to practice.