More than two decades ago, on January 24, 2004, I landed in Baghdad as a legal consultant and was assigned an office in what was then known as the Green Zone. It was cold and raining, and my travel bag was thrown into a puddle of water outside the C-130 plane, which had just made a spiral descent to reach the runway without risk of ground fire. I was greeted by young American soldiers as we piled into a vehicle, speeding out of the airport complex and heading down a road called the “Highway of Death” because of car bombs and snipers.

“What has our country gotten itself into?”

That was my first thought during that harrowing trip. Over the course of a year in the country, and then through successive presidential administrations, I have often advised prudence and caution in defining the objectives of American foreign policy. Especially when it comes to the use of military power, the application of which must be linked to clear, articulated and achievable objectives.

One might think that the current situation in Venezuela — where the US has now deployed 15% of its naval power and where it is carrying out land exercises nearby — would serve as a warning to stop before the country finds itself, once again, in a situation it does not fully understand and with uncertain consequences.

But maybe it’s not quite like that.

The current situation in Venezuela bears little resemblance to Iraq and is much more similar to Panama 35 years ago, before the US military operation to remove a dictator and install an elected government that enjoyed widespread support from the local population. This mission was a success and Panama is today a functional democracy, friendly to the USA, although not without problems, from crime to corruption.

Is it possible that we are so paralyzed by the experience of Iraq (and Afghanistan) that we miss an opportunity to improve the lives of Venezuelans and stability in our own hemisphere, following Panama’s example?

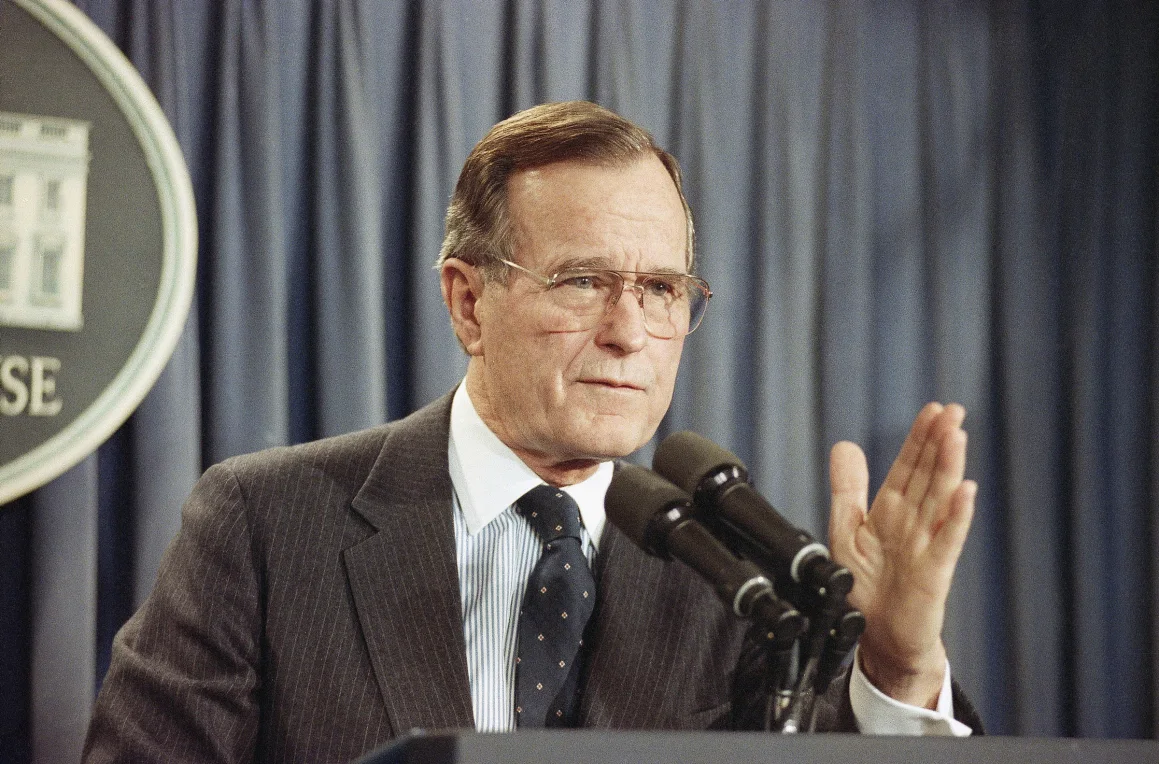

United States President George HW Bush responds to a question during a press conference on December 22, 1989. Bush said he will not be satisfied until Manuel Antonio Noriega of Panama is brought to justice and that the United States will pursue him “as long as necessary.” (Ron Edmonds/AP)

Venezuela and Panama: Similar pretexts

On December 20, 1989, President George HW Bush addressed the nation to define the basis for the mission he had just ordered in Panama. He explained that Panama was led by an “accused drug trafficker”, Manuel Noriega, who would soon be “brought to justice” in the US. Bush added that Noriega had nullified democratic elections and that the winners of those elections would soon take power in Panama City, likely with broad support. The Noriega regime also threatened and harmed Americans, including the recent death of an American soldier, shot by Noriega’s security services.

Finally, Bush discussed the strategic importance of the Panama Canal and Washington’s commitment to existing treaties that Noriega was unlikely to honor.

In this scenario, Bush explained the objectives of the mission: “Safeguard the lives of Americans, defend democracy in Panama, combat drug trafficking and protect the integrity of the Panama Canal Treaty.”

Two weeks later, Noriega was in U.S. custody, the elected opposition government took power, and U.S. forces began to leave the country.

I recently spoke with a former US military colleague who participated in this operation, parachuting into Panama before Bush’s speech. “Of all our military adventures since Korea,” he told me, “Panama must be considered one of the most successful. To go there now is to see a very prosperous democratic country.”

US soldiers transport a large crane to the area near the Vatican Embassy in Panama on December 30, 1989. (Corinne Dufka/Reuters)

Let us now look at Venezuela.

The country is governed by Nicolás Maduro, who, like Noriega, faces criminal charges in US courts. The accusations against Maduro are more extensive. His 2020 indictment in New York lists crimes of narcoterrorism, drug trafficking and corruption. He is also accused of heading the trafficking organization “Cartel dos Sols”, which the State Department has just classified as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. Washington has offered a $50 million reward to anyone who helps put Maduro in US custody.

Like Noriega, Maduro also invalidated successive elections and violently suppressed democratic movements within his country. The US and most of its Western allies recognize the opposition led by Maria Corina Machado as the legitimate government of Venezuela. According to independent observers, opposition parties received 70% of the national vote in the 2024 Venezuelan presidential election, which Maduro claims to have won.

Finally, Maduro, like Noriega, has threatened and harmed American citizens as well as regional peace and security. In recent years, like his allies in Iran, Maduro has effectively held Americans hostage for diplomatic maneuvers with the US. These hostages include an American sailor on vacation in Venezuela, longtime American residents of the country and executives from Citgo, the American subsidiary of the Venezuelan state oil company.

In 2023, Maduro threatened to invade neighboring Guyana, an American ally, and today claims sovereignty over two-thirds of Guyana, justifying the claim — just like Putin in relation to eastern Ukraine — based on a false story and a staged referendum.

Significant differences

If Maduro is replaced in Caracas, there is no guarantee that local authorities across the country will work with the new government, opening the prospect of civil wars and violent competition for power and resources. Maduro claims to have recruited a militia numbering in the millions to resist any US-backed operation, and while this claim may be exaggerated, we must assume that drug cartels could take control in rural areas, as opposed to the forces of democracy we might hope or wish to see prevail.

Venezuela is more than ten times larger than Panama, something that would lead military planners to recommend a force far superior to the almost 26,000 troops deployed in the 1989 operation.

The geostrategic context is also very different. In 1989, the Soviet Union had collapsed, with the fall of the Berlin Wall six weeks before the US invasion of Panama. America was the undisputed great power in the world and there was no reason to expect or anticipate that other great powers would resist the military operation or make their own moves in other hemispheres.

Today, Russia and China are aligned with Maduro and their leaders would likely cite any US operation in Venezuela as additional justification for pursuing their own hemispheric ambitions, against Ukraine and Taiwan, respectively.

What are Trump’s options?

Donald Trump said last week, cryptically, that he had “decided” on the course of action in Venezuela. This followed CNN reports of multiple high-level meetings at the White House with military commanders about options following naval build-up off the coast and exercises conducted by the US Marine Corps (Marines) in rural and urban areas of Trinidad and Tobago.

Maduro appears to be interpreting these movements as a possible American intervention, calling on his militias while calling for dialogue, even singing John Lennon’s peace anthem, “Imagine”, at a recent rally.

People watch the USS Gravely, a United States Navy warship, from Port of Spain on October 30. The US warship arrived in Trinidad and Tobago on October 26, 2025 to carry out joint exercises near the coast of Venezuela. (Martin Bernetti/AFP/Getty Images)

Adding to the confusion, the administration has not been clear about the objectives of what it now calls Operation Southern Spear. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth described the mission as being to “defend our homeland, remove narcoterrorism from our hemisphere and protect our homeland from the drugs that are killing our people.” Although there was no mention in official statements of the reestablishment of democracy in Venezuela, or of a goal of seeking Maduro’s removal as leader, Trump declared that Maduro’s days are “numbered.” Military deployments, including the most advanced carrier strike group in the U.S. arsenal, suggest ambitions beyond Southern Spear’s publicly stated goals.

Certainly, Maduro’s removal is in the interests of the US and the people of Venezuela. Before the government of Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, the country was among the most prosperous in South America, whereas today it is in ruins, with per capita income falling 72%, one of the most severe economic collapses in history. Credible polls indicate that more than three-quarters of the country opposes his government and there is an opposition government prepared to take power if given the opportunity.

The Trump administration, despite shows of force, appears unlikely to pursue regime change through military means, a course of action that would run counter to its stated aversion to prolonged military engagements. Nor would I advise them otherwise. At this stage, the differences in relation to Panama outweigh the similarities or the hope that an operation against Maduro could go as well as in Panama more than three decades ago.

But the administration must not withdraw the influence it has now built against Maduro, but must use it effectively.

Without resorting to a military operation to overthrow Maduro, the administration could demand that he hand over key figures in drug trafficking networks inside Venezuela, drop claims on Guyana and commit to holding new elections with international observers, which he would certainly lose. To go further, the administration could demand his exile, perhaps to Russia, where he could join Bashar al-Assad, the former president of Syria, another dictator who destroyed his own country for the sake of personal power. For any of this to work, the administration would need to secure the support of allies, including in South America, something it has to date been unable or unwilling to do when it comes to its goals in Venezuela.

Members of the Bolivarian Militia participate in civic-military training, amid growing tensions with the US, in Caracas, Venezuela, on November 15. (Maxwell Briceno/Reuters)

In any case, before the US embarks on a policy to replace Maduro, whether through military or other means, there should be a debate in Congress to weigh the pros and cons, something that also does not happen today due to the dysfunction in Washington.

Conclusion

The US, after two decades of prolonged military engagements abroad, is rightly wary of any new venture that envisions regime change. This caution is justified, but in Venezuela the arguments for Maduro’s removal from power are compelling and draw more parallels with Panama than Iraq. However, strengthening military power offshore can be better used to achieve objectives that ultimately do not require its use at home.